‘Our sacred sites need to be saved’

STANDING ROCK— When Tim Mentz was five years old, he had his hands painted red in ceremony, so he could carry the dead. He became a member of the Red Hand Society, which went all the way back to his great, great, great grandfather Chief Big Head of the Cuthead band, about whom his grandmother passed on the knowledge and history.

“My grandmother was born in 1891,” Mentz said. “She died in 1968, so I had all those years of her coming from the first source, Chief Big Head, of the Red Hand Society, of where these (spiritual sites) were, but I had never been to them and couldn’t get to them because they were all on private land. But I got exposed to them on our reservation, when we went out hunting, when I was growing up, we would come up on a site…we were really careful, and I started to see all the beautiful sites, the genesis of our spirituality. This is where the spirits were, they’re pretty active, and they’re still there.”

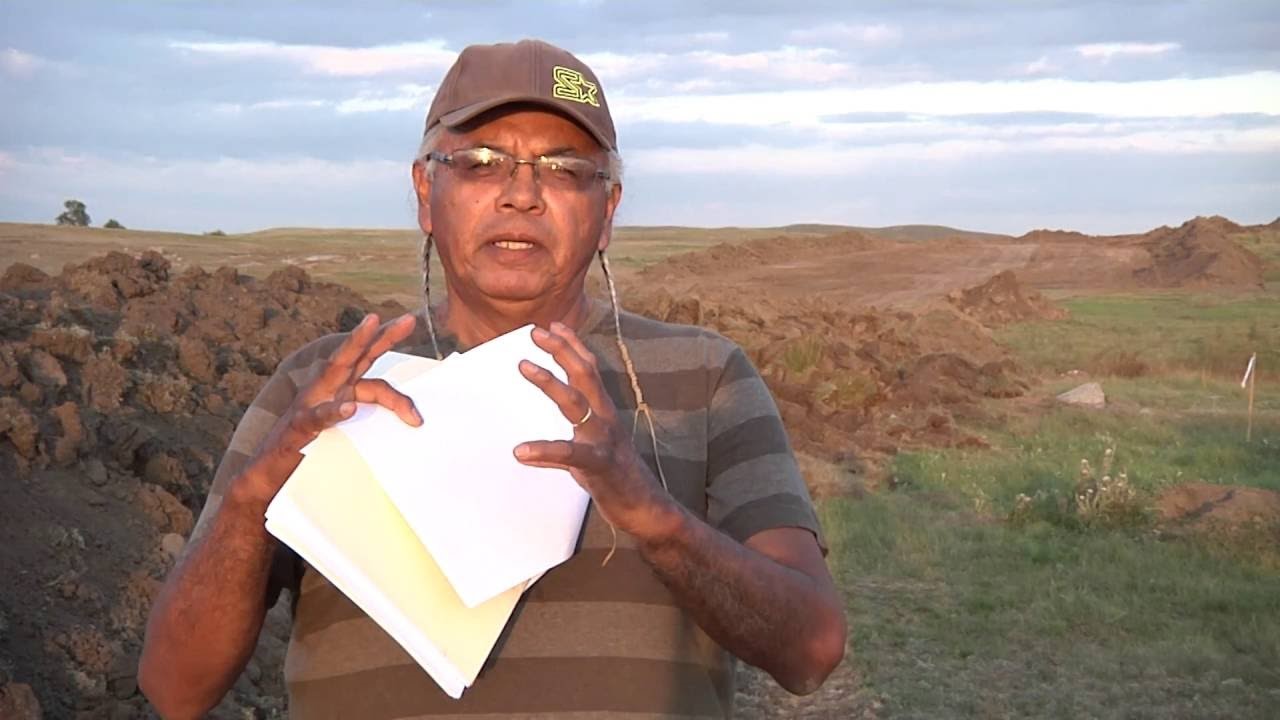

While he is perhaps the leading expert in the world on the spiritual sites of the Oceti Sakowin, and his family history has immersed him in an understanding of the spirituality few people on earth share, Mentz is not a traditional in the sense most people might figure. He has no college degree, but his comprehension of the law and the history necessary to protect these sacred sites from dominant culture destruction rivals that of any tenured academic, and his ability to articulate that knowledge exceeds any man yet living.

“I’m a Dakota/Lakota, I carry both sides,” Mentz said. “I was born in Cannonball, North Dakota, along the Missouri River in a two-room log house. I finished up boarding school in Fort Yates in 1972. Went to welding school in Sacramento for two years. Starting in 1977, I worked for the tribe for 33 years, different positions.”

Mentz had two uncles, Sam Little Owl and George Iron Shield, and they recognized early on that Mentz need to be mentored and directed, that he would be the one, that he had an earnest mission, filled with grave responsibility, to protect sacred sites, and educate the tribe on how to protect them.

“In 1978, as a young man, I was with my uncles,” Mentz said. “We started to go out to federal projects, particularly in North Dakota, where they were unearthing human remains, so I kinda got pulled into this through my uncles. I got to the point I was taking them around to a lot of the projects and we were going to make sure that sites we knew that had stone features, and were important to us, were protected, and we took on the issue of human remains in 1985. It was because of the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act. So my involvement started pretty young. I was brought up in this environment of protecting certain areas and I progressed to where I started to hang out with my uncles. After 1978 I started diving into various laws, being self-taught. At the time I had exposure to one of my mentors, was really a good friend of mine. I really appreciated his indulgence, of giving me and sharing with me information, and that was Vine Deloria, Jr. Vine was really somebody that I treasure. I also hung out with a number of the tribal officials. Particularly with the individuals that not only had an academic background but also were part of the Black Hills Sioux Nation Treaty Council. Of high interest in 1985 was human remains and how the states lacked laws.”

There was no formulated process, no negotiated ground. Over the next decade Mentz would be at the forefront in hammering out the policies and procedures for protecting tribal sacred sites we have today. But the activism aspect started in 1985, when a Yankton Dakota activist, Maria Pearson, battled for the return of human remains unearthed during road construction.

“There was an Indian woman in full buckskin regalia and she had a little baby next to her, that’s what started the NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) movement. They shipped off the lady and the baby to the historical society in Iowa. They finally returned the remains and we helped bury them and what was important about that is it started the movement of how tribes look at the problem of how federal projects were inadvertently but unearthing our relatives and they were shipping them off to study them.”

The battle for NAGPRA honed the skills Mentz would need later on, and taught him to get what you can but not lose sight of what was required in the long run. Mentz: “NAGPRA was really a Fifth Amendment rights issue on the disposition of human remains but only on federal land and that’s where we lost. We lobbied for it to be put unilaterally on all lands but certain congressional people whittled it down to where it applied only to federal land and or tribal land.”

The most important victory came in 1992. In 1966 Congress had passed the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), requiring “federal agencies to evaluate the impact of all federally funded or permitted projects on historic properties through a process known as Section 106 review.” State Historic Preservation Officers (SHPOs) were established to “coordinate statewide inventory of historic properties, nominate properties to the National Register, maintain a statewide preservation plan, assist others, and advise and educate the locals.”

There were two major problems with that set up for tribes. SHPOs were extending their authority into tribal areas where states actually had no authority, and they were ignorant of the critical aspects of tribal sacred site preservation, including how to even identify or understand what constituted a site. Many is the archaeologist boot that trampled right over sacred rock features thinking they were just rocks.

“We have every right to say what is important to us,” Mentz said. “The SHPOs have a national group, the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers, they were fighting us up on the Hill saying the tribes don’t have any rights outside reservation boundaries, on tribal land and federal land, to say what was important to them. It was really a tough issue at that time. We got our way, establishing a Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (THPO). That person had responsibility within the reservation boundaries as a state historic preservation officer, so we took that away from the states as having jurisdiction over anything that had a federal dime, federal involvement, federal attachment, and federal assistance even.”

According to Mentz THPOs established the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty boundary, 66 million acres, as their expressed interest.

“Before federal dollars can be expended on a project,” Mentz said, “They have to have the THPO ensure that all the resources are identified, evaluated, and if their evaluation is they are very important, then they get nominated to the National Register of Historic Places, so that’s the three steps of Section 106. The THPO has to have his signature on that project before it goes forward and those federal dollars can be expended.”

It would take four years for the first THPO to be created by a tribe, and that tribe was the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and the first THPO in the nation was Tim Mentz. On the one hand, Mentz was ready for the job: “I’ll tell you, I was so primed at that time. I knew the law in and out because I studied it and I had an ace-in-the-hole, I had Vine Deloria, Jr., sat in the back and he said don’t put me up front but I’ll help wherever I can.”

On the other hand, there was a limit to how much sacred knowledge Mentz could share in order to protect places that were sacred: “Those who were part of the Black Hills Sioux Nation Treaty Council, were telling me be careful what you share with (the feds), maybe this is not the right time. In 2000, we started to do ceremonies, every five years it was suggested to have ceremony, (to decide) when to expose this information.”

Mentz gave an example of the type of problem even an extremely knowledgeable THPO respecting the wisdom of elders faces: “What they call a hanbleyca ring, in 1954-55 there was an archeologist in Montana said those are habitational rings, they hold down the tipi. All those years I knew what they were but I never challenged them because the old people told us not to challenge them, just let them be like that, that’s okay. It got so repeated that was the norm, they said, no, those aren’t sacred sites, those aren’t special places, because those hold down the tipis.”

Near the end of his 12-year run as tribal THPO, Mentz came face-to-face with the deeper threat to the spiritual well-being of the Oceti Sakowin: “In 2005, in ceremony, they told us now get ready, get ready to tell this story. We have to start telling them now because the young ones need to know, they’re curious.”

Mentz had waited many years, unable to share sacred knowledge because it was not time, but now that it was time, the THPOs had sadly gone off the rails, and lost sight of their purpose and their mission.

“We got into these big federal meetings,” Mentz said, “and they were saying, well tell us what’s important to you. Nobody would say anything, and I finally realized that all my colleagues never knew a clue because they never got out there.”

One of the responsibilities of the Red Hand Society is to protect the stone features of sacred sites. These stone features can be spectacularly elaborate, and on one federal project, near Williston, Mentz and his team located and identified 8111 sacred stone features.

“We were sitting back waiting for when the spirits said now is the time to start talking,” Mentz said. “Now they are ready, now people are ready to hear this. We formed our company, and the reason we called it Makoce Wowakpe (Earth Writings), was you’re going to do something, you’re going to protect makoce wowakpe. One day you’re gonna stand there and protect these places.”

Mentz trained many people, made may others far more knowledgeable, during the years his company mapped sacred sites, but a problem soon arose. A conflict brought about by small mind greed, by tribal members ignorant of the bigger picture and purpose.

“THPOs are not telling their tribal leadership what is required of the law, what their responsibilities are, and here’s the regulations, what you can do out there,” Mentz said. “None of them are doing that because none of them read, none of them know. Park Service should be stepping in, not only training the THPOs, but they should be training the tribal government.”

The family company Mentz started could train every THPO on how to protect sacred sites, but the THPO agenda has become one of grabbing consultation fees on top of their TYPO salary.

Sacred sites stretch from Canada down to Kansas. Together they reveal a strategy to save the earth, according to Mentz.

“My son, Tim Jr,” Mentz said, “I really don’t know anyone that is at his level. Not only can he recognize and record but he has a gift and that gift is communication, and we all communicate at these sites and we have no alcohol or drugs or anything. The prophecy is we are supposed to give this information to the Seventh Generation, they’re coming and they are going to be ready for this information because what the prophecy said is we’re supposed to walk back to these places and the Nation is going to step up and save the earth. Every time I hear about a stone feature being destroyed, we are chiseling away at our spirituality, and our gift.”

“It’s not about money,” Mentz said. “It’s about saving those resources that are so important to us. Yet the THPOs are not on that page. They don’t get off the road anymore, they don’t see what’s on top of that hill. They don’t understand how fragile our spirituality is.”

They don’t see Mentz as a tribal elder with important wisdom to share. A broken THPO system must be returned to its original intent if the sacred sites of the Oceti Sakowin are to be saved.

“While I’m still here on this earth I could really help, but they don’t want help,” Mentz said. “Because they’re used to putting people out in the field and they are used to having archeologists do all their work, put the report together and say what’s important for them. They don’t want to understand the law, don’t want to know the mechanics of it, and they don’t know how to implement it.”

(Contact James Giago Davies at r1e2n3fmk@gmail.com)

The post ‘Our sacred sites need to be saved’ first appeared on Native Sun News Today.