A brief history of the pow wow

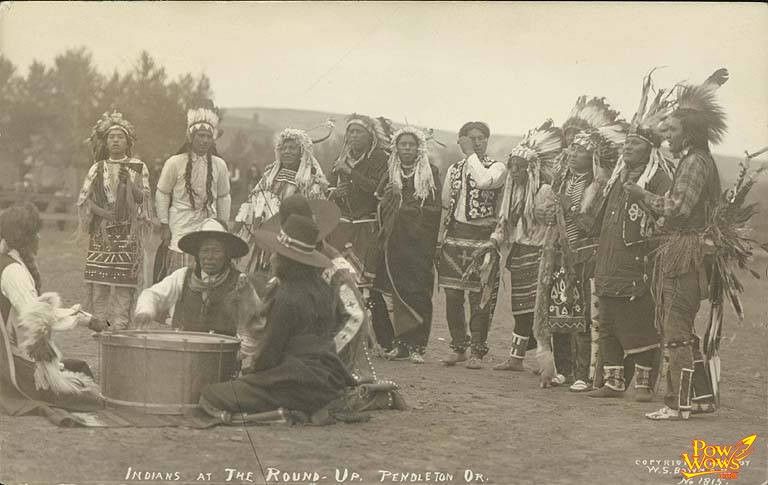

1910 Pendleton, Oregon Round Up Pow Wow (Photo courtesy pininterest.com)

History wastes little time distorting who people were, why they did the things they did, and unless a given piece of history was lucky enough to have a skilled, principled scholar on hand to jot down every important particular, perhaps the only thing that survives intact is the spirit or intent behind the history.

When we look at the history of pow wows we do not have much tribal history, passed down through stories and winter counts, to fall back on, and so despite pow wows being an important part of most tribal communities, the real history of pow wows is being made by people today, by just having pow wows.

Unlike the pow wows of the distant past, modern pow wows are being recorded, chronicled, and people are living the history, as performers, vendors, attendees. Generations from now a detailed record of the how and why of our present day pow wows will be readily available.

But what of the spirit and intent? What can we piece together from the historical record from varied and obscure sources to trace pow wow history? Since the tribal history is hard to find we are left to what white historians can glean, and as this must always be filtered through the prism of an alien culture, it will tend to reflect their sensibilities.

The earliest information on pow wows comes from an Algonkian people called the Narrtick, who called Massachusetts home when Europeans first arrived. Apparently they had a term “pau wau,” meaning “medicine man,” which later became pow wow. How the Narrtick spelled pow wow, “pau wau,” when they had no written language, is one of those things white historians often forget to ask themselves.

It is claimed, by no identifiable source, that the white folks misinterpreted the word to mean all tribal gatherings, when it seems to have originally applied only to a meeting of tribal elders, men of prestige and importance, for deeply spiritual purposes, or grave concerns that threatened the people.

Grass Dance societies formed in the early 19th Century, and it is alleged that the modern pow wow was derived from this period. Warriors were said to reenact brave deeds at these grass dances, presumably through dancing, and obviously, the more ritualistic, and visually stunning the performance, the more people would have liked it and clamored for more.

Interlaced with all this warrior dancing would have been socializing, gift giving, and the most elemental and meaningful bonding ceremony for any tribe in human history—eating. What would a pow wow be without good eats?

The darker truth about the transition from grass dance to pow wow, came from the white perception of Native spirituality as a threat, where it inspired and compelled young men to go “on the warpath,” and it reinforced traditional beliefs and social order, both of which obstructed assimilation, which was the key component and ultimate goal of the Discovery Doctrine as detailed by Chief Justice Marshall in 1822.

In 1883 the Interior Department urged that heathen practices be eliminated, and argued for the discontinuation of dances and feasts. In 1884, Indians found guilty of participating in traditional ceremonies received 30 days in prison. In 1892, Congress imposed even more stringent restriction, expanding violations to include even Indians who advocated traditional belief. The prison sentences were stiffened.

A curious mixture of celebration occurred over the next fifty years. On the one hand, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show introduced the traditional Indian to the world at large, highly romanticized, but in a positive light for the audience. This was important because it was an end around to offset the Draconian religious restrictions being imposed on the reservations. At some point, the public melded the pow wow and the Wild West Show into a single celebratory perception of tribal traditional ceremony, and whatever the law on the books might still be, the public began to see Indian spirituality and ceremony not only in a positive light, but as festive, charming, entertaining.

Eventually white communities worked hand-in-hand with reservation communities to form gatherings like the Crazy Horse Celebration, which was held near Hot Springs, but which ended a half century back over a Lakota man found murdered in a ditch.

One of the first obstacles of the early pow wow circuit was burying the hatchet between tribes that were traditional enemies. Although some of this animosity still persists, for the most part, pow wow participants have come to see themselves as Native first, and tribally distinct, second. Although many would argue that point, at least to the white attendees, Natives as a single identity register far more frequently to whites than Natives as a distinct tribe.

As the pow wow circuit has become more enterprise than spiritual, the danger is that a generic pow wow identity will be formed connecting all tribes by a thread that does not honor the history or meaning behind the ceremony. For this reason many local tribes retain traditional names and perspectives, such as the Lakota Healing Hoop Pow Wow, which began in 2015 in Northglenn, Colorado. According to their mission statement at their website, the Healing Hoop Pow Wow is “focused on creating community-based and community-led solutions that strengthen the cornerstones for a good quality of life: spiritual connection, education, financial stability, health and community involvement.”

As the pow wows grew in popularity, hoop dancers like Dallas Chief Eagle developed their skills and understandings into a program presented to an audience, a program filled with dancing, stories, and humor. Kevin Locke took this one step further and his website describes him as being known throughout the world as “a visionary Hoop Dancer, the preeminent player of the indigenous Northern Plains flute, a traditional storyteller, cultural ambassador, recording artist and educator.”

Many people use the pow wow circuit as a road map, to schedule their summer travels, and it has become much more like the traditional coureur de bois rendezvous back in the early 19th Century, where mountain men, merchants, and Indians would gather in a celebration of life, and commerce.

Enter casinos, the face of modern Native identity to most white folks. Casinos saw the profit in helping promote pow wows, correctly figuring the crowd would spill over from the pow wow to the casino.

As the pow wows have become more commercialized, ironically, the competitions have become more traditional, to appease those who feel sacred ways are being exploited for money.

As time marches on, all of the historic aspects of the pow wow are forming a combined hybrid pow wow reality, which attempts to incorporate every vital aspect without one dishonoring the other.

(Contact James Giago Davies at skindiesel@msn.com)

The post A brief history of the pow wow first appeared on Native Sun News Today.