The struggle to keep the Cheyenne language alive

A Tribal Language Story Part III

A Tribal Language Story Part III

This final segment of the Northern Cheyenne language story as related by knowledgeable tribal members, looks at contemporary language preservation efforts among the Northern Cheyenne in Montana. This is but one example of how tribal peoples around the world struggling to keep their unique tongues alive.

Ever a resilient people, by 2022, the Northern Cheyenne have rebounded from less than one thousand people in 1884, when their Reservation was established to 12,116 enrolled members. This is in large part due to a reduced blood quantum requirement reports Wallace Bearchum, fluent speaker, and Director of the Tribal Enrollment Department. “Only about 5,100 live on the Reservation, the only place on earth where we still speak Cheyenne every day,” he told Native Sun News Today.

Other urbanized tribal members are scattered throughout the world, with seldom an opportunity to hear or speak the Cheyenne language.

Thankfully, there is a written version of the language and a dictionary which even includes audio pronunciation and is now available on-line at cheyennelanguage.org.

The dictionary is due to the early efforts of scholars such as Rodolphe Petter, a Mennonite minister who spent his life among the Cheyenne, learning to talk and write the Cheyenne language in consultation with elders.

“This is another resource available for language preservation,” commented Littlebear.

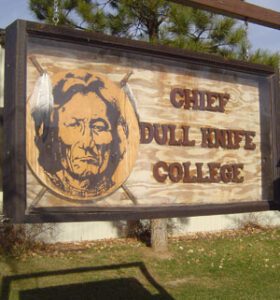

On the other hand, Chief Dull Knife College (CDKC) estimates there are several hundred members on Reservation who have some language proficiency. Many routinely use common expressions such as “Good Morning;” “Thank you;” “What did you say?” or the standard farewell “I will see you again” and the language is still used extensively in Cheyenne jokes, a favorite past-time for all Cheyenne people.

Wayne Leman, a non-Cheyenne, a linguist teaches an on-line language class that promotes Cheyenne language acquisition for serious students. It focuses on spelling and writing the language. The on-line class conducted through interactive ZOOM technology has proved popular with both young and old aspiring Cheyenne speakers. The students are both on and off-reservation residents, including several non-Indians. Leman said that the class appeals to students from around the world including communities near the Reservation, Nevada, England, Spain, Australia, Oklahoma and of course the Reservation.

The class meets once a week on Wednesdays. More information can be obtained at: cheyennelanguage.org. Participation is free.

Lehman, a trained linguist runs the session on a volunteer basis. He and his wife Elana, also a linguist have collaborated with the Northern Cheyenne since 1975.

An Alaskan Native, Leman is a member of the Ninilchik Traditional Council, who have lost their language due to the influence of Russian colonists. “I don’t want to see that happen to other native people,” he commented. “To learn a language, a person must hear it spoken and speak it regularly. Many contemporary Cheyenne, especially those living off reservation do not have that opportunity.”

In addition, to Leman’s effort several tribal members who speak fluently are utilizing contemporary internet to promote language preservation. Mina Seminole, CDKC cultural resources director mentioned the efforts of Conrad Fisher, former Tribal Vice-President, Rosalie Bad Horse, a graduate student, and Benji Speelman, recent college graduate.

The Tribal College, with the support of the Tribal Council and various language preservation grants is conducting a strong campaign to preserve and revitalize their language. For example, students at CDKC must complete credit hours in both the Cheyenne language and Native American studies to graduate.

Burt Medicinedbull, tribal member, and educator has provided four levels of Cheyenne language classes since 2011. During his twelve years of teaching at CDKC, he estimates that at least 250 Cheyenne have completed the core classes, many of those continuing to more advanced levels.

Medicinebull told Native Sun News Today he finds face-to-face instruction most effective. Personal interaction is essential he says, in large because the Cheyenne rely heavily on body language when communicating. He has, however found that cell phone recordings are a useful learning tool for students. He uses a variety of teaching techniques, based on Cheyenne language curriculums that have been developed over the years.

Soon, Medicinebull will incorporate sign language into the curriculum. “Signing is also in danger of being lost but is part of the way we communicate.”

The State of Montana has also recognized and passed laws to encourage preservation of Montana tribal languages. There are two key laws to that effect.

First, Class 7 Certification of tribal language speakers, enables them to teach in Montana Schools was enacted in 1995.

Second, the Montana Indian Language Preservation Project (MILPP) enacted in 2013 provides grants to Tribes for language preservation efforts. This, however, is not in the Montana base budget, subject to annual legislative fights to secure ongoing funding.

Participation in such programs is voluntary for most Montana schools. The process for acquiring a Class 7 certificate is left up to local school boards or the Tribal Councils. Urban schools with significant native student populations can also participate in either the MILPP or the class 7 Program, with marginal results.

Northern Cheyenne schools on and near the reservation utilize Class 7 certified instructors to provide active Cheyenne language classes at all levels. The classes are provided by the Headstart Program, Lame Deer Public Schools, St. Labre Indian Academy, the Northern Cheyenne Tribal Schools, and the Colstrip Public Schools.

At Northern Cheyenne, eighteen Cheyenne speakers gained Class 7 certification. These certified instructors have devoted their professional careers and personal lives to teaching and preserving the language. Unfortunately, they are oftentimes not paid on par with other Montana certified teachers.

The Northern Cheyenne who have gain Class 7 certification include: Dr. Richard Littlebear, Alvera Cook, Victoria Cook, Allen Clubfoot, Adeline Fox, Seidel Standing Elk, Burt Medicinebull; Christine Medicinebull, Larry Medicinebull, Elizabeth Braided Hair, Elena Whitedirt, Kathy Wilson, Eugenia Russell, Joyce Wounded Eye, Rose Birdwoman, Jackie Tang, Rebecca Littlesun and Jolene Waters Walkslast. All are tribal elders, thus Seminole said there is a critical need to enable younger tribal members to gain such certification.

Currently, the Cheyenne language is primarily spoken on the Reservation where the hub of speakers lives. Often, according to linguists such as Leman, the best way to learn a language is immersion, speaking daily, naturally to live, rather than through memorization and drills. An apt adage seems to be “use it or lose it.”

That is why many tribal members, especially elders say it is critical to develop more fluent speakers. “It requires a critical core of speaker to pass the language on,” Littlebear said.

Tribal peoples across the country are mounting similar defensive educational campaigns, according to Jonathon Windy Boy, Chippewa Cree, Rocky Boy Reservation. Windy Boy, a State representative who introduced MILLP and continues to monitor the tribal efforts made under that law. He heads up the Chippewa Cree language program on the Rocky Boy’s Reservation.

Recently the State of Montana provided grants for another round of tribal language preservation projects. Each of the eight Montana Tribes is eligible. Since there is no standard curriculum available for teaching tribal languages, staff in tribal language programs have been innovative in developing teaching strategies, the preservation of oral histories, elder stories, utilizing contemporary technology as teaching tools.

“It’s time to write our languages and accompanying histories,” Littlebear noted. “We are rapidly losing our speakers and by default many of our stories and some customs. In the old days, when I was young, we learned the language by living with Cheyenne speakers. We did not have drills or tests, memorize words or phrases. We just talked it and though everyone makes mistakes as a beginner, eventually you get it right. Even now, as an elder I still make mistakes. It is okay.”

“Those days of learning that way are quickly ending. It is our responsibility to provide younger people with the tools to learn the language after us old ones are gone. I hope they will want to do that,” Littlebear concluded.

(Clara Caufield can be reached at acheyenne voice@gmail.com)

The post The struggle to keep the Cheyenne language alive first appeared on Native Sun News Today.