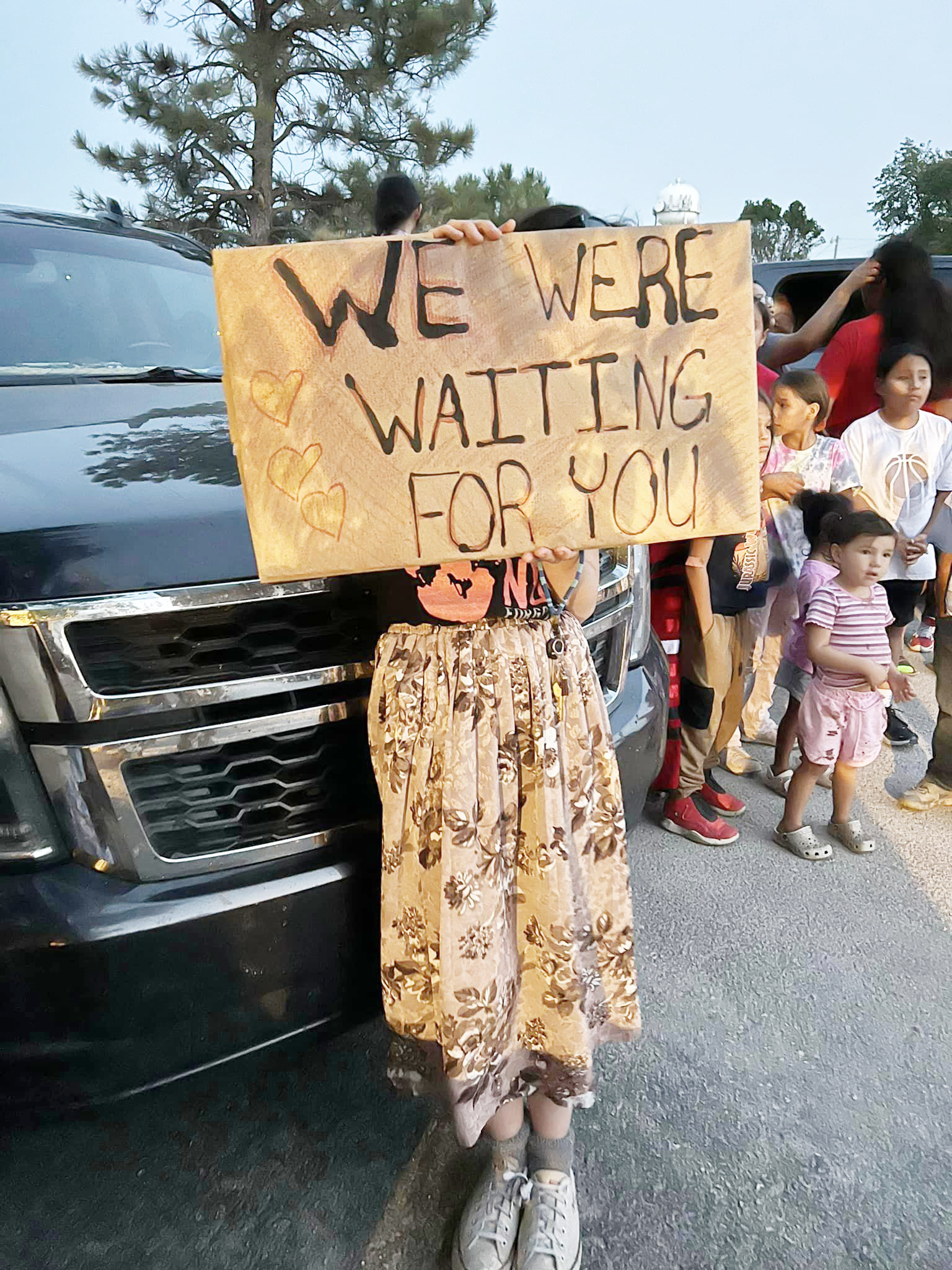

Oglala children return from Pennsylvania boarding school cemetery

As the caravan bringing home the remains of three Oglala Lakota children from the Carlisle Industrial Boarding School, they were met by a person holding a heartfelt sign that read, “We were waiting for you.” (Photo by Jenn Spotted Bear)

By Grace Terry

Native Sun News Today Correspondent

PINE RIDGE, SD – Three Oglala Lakota children originally from the Pine Ridge Reservation came home this week from the Carlisle Industrial Boarding School in Carlisle, PA, where they died and were buried more than a century ago. The three were included in the 2024 Office of Army Cemeteries’ annual process of disinterring, identifying, and returning the remains of Native American children who died at Carlisle.

Over the last seven years, the Army has returned 32 Native American childrens’ remains back to their relatives, including the remains of 9 Lakota children returned to the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota in the summer of 2021. More than 160 remains are still waiting.

Each annual project was conducted by a team of professionals from the Army Corps of Engineers’ Center of Expertise for Curation. The team worked with tribal nations to carry out the process of exhuming and identifying each child’s remains. The Army confirmed that it will be disinterring and returning an additional 18 children in 2025.

The three Oglala children from the Pine Ridge Reservation included Fanny Chargingshield, James Cornman, and Samuel Flying Horse. They are among nearly 200 students who died and were buried in the government’s care between 1880 and 1910 while attending Carlisle.

Many students’ deaths were announced in the local newspaper at the time, noting causes of death as “that dread disease, consumption,” now known as tuberculosis, or detailing circumstances of unknown sickness.

According to archival records at Carlisle:

– Fannie Charging Shield arrived at Carlisle on February 19,1891, and died on March 7, 1892, at age 16;

– James Cornman arrived at Carlisle on August 12, 1887, and died on April 21, 1891, at age 22;

– Samual Flying Horse arrived on June 24, 1891, and died on May 31, 1893, at age 18 of consumption.

Regarding Charging Shield, the local newspaper reported on March 11, 1892, “In last week’s (newspaper), we noted the fact of the coming of Chief Charging Shield, Sioux, to see his daughter, Fanny, who was ill. This week we are compelled to give the sad news of her death, which occurred on Tuesday. The funeral took place on Wednesday morning, Rev. Alexander MacMillan, Rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church, Carlisle, preaching the sermon.”

Other Native American children returning to their homelands in this year’s project include William Norkok from the Eastern Shoshone Tribe; Almeda Heavy Hair, Bishop L. Shield, and John Bull from the Gros Ventre Tribe of the Fort Belknap Indian Community; Albert Mekko from the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma; and Alfred Charko and Kati Rosskidwits from the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes. One additional tribal nation receiving their relative’s remains wishes to remain anonymous, according to a spokesperson from the Office of Army Cemeteries.

According to explorepahistory.com, about 10,000 students attended the Carlisle School from its founding in 1879 until it closed its doors in 1918, representing more than seventy different Indigenous tribes.

Colonel Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle School, had served in the American Civil War and then as a commander of African-American cavalry troops in the Plains Indian wars. In 1875, he was placed in charge of a group of Plains Indian prisoners held at a military prison in Fort Augustine, Florida.

Pratt decided to train the Native American prisoners for life in white America by stripping them of their Indian heritage and culture. He took as his model federal schools that were operating at that time for former slaves in places like Hampton, Virginia, where he took some of his Indian students.

In 1879, Pratt successfully petitioned the federal government to expand on his experiment by converting the old army barracks in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, into a boarding school. Pratt recruited Native American students from across the United States.

Pratt summed up his educational philosophy in the phrase, “Kill the Indian, save the man.” He is also known to have said, “In Indian civilization, I am a Baptist, because I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization and when we get them under, holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked.”

The typical student at Carlisle was between fourteen and eighteen years old, although some were much younger. Boys and girls were segregated by sex, the boys wearing military-style uniforms and the girls European-style dresses.

The Indigenous children, homesick for friends and family, chafed under the school’s dress codes, rules, and discipline, which included generous corporal punishment. Boys were put to work learning occupations like printing and tinsmithing, while girls were trained in domestic arts such as sewing and cooking.

The Indigenous children, homesick for friends and family, chafed under the school’s dress codes, rules, and discipline, which included generous corporal punishment. Boys were put to work learning occupations like printing and tinsmithing, while girls were trained in domestic arts such as sewing and cooking.

Carlisle was used as a model for hundreds of government-and-church-funded boarding schools across the United States. Like Carlisle, the schools typically were underfunded and understaffed and often the children were subjected to physical, emotional, spiritual, and sexual abuse and neglect.

Colonel Pratt fell out of favor with officials at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1904 and lost his job running the Carlisle School. One of his contemporaries wrote, “He is an honest lunatic.”

Carlisle remained open for fourteen more years. Historians estimate that one in eight of the Indian students who matriculated there graduated. Many others dropped out, ran away, or died from illnesses compounded by homesickness.

Pratt’s vision of Indian education persisted in the United States much longer than the Carlisle School. It wasn’t until the latter part of the twentieth century that the pendulum had swung back from forced assimilation by boarding schools and other methods to policies for the protection and preservation of the Natives’ cultural heritage.

At Pratt’s time, his methods and objectives were considered by many whites and Native Americans alike to be the best chance for Native survival in modern America. By today’s standards, they are atrociously racist and abusive.

On returning to the reservations, boarding school students often found themselves alienated from their people, trained for jobs that did not exist, ostracized by their peers, and still victimized by white prejudices. Even those Native American survivors of boarding schools who found success among whites often suffered a sense of profound loss regarding their Native heritage. Their families continue to suffer from intergenerational trauma directly related to boarding school abuse.

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) (www.boardingschoolhealing.org) has been a leader in a grassroots movement of boarding school survivors and descendants, tribal leaders, Native academics, researchers, and advocates who seek truth, justice, and healing for boarding school impacts.

NABS does not require a membership fee for individuals to join and there are no annual membership dues. More information including the membership application is found at boardingschoolhealing.org/about-us/membership/. Those who wish to make a donation to NABS, may do so at boardingschoolhealing.org/about-us/donate/

Survivors of residential schools or their descendants in need of support can call a toll-free line at 800-721-0066 or a 24-hour crisis line at 866-925-4419, a service sponsored by the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FISN).

(Contact Grace Terry at graceterrywilliams@gmail.com)

The post Oglala children return from Pennsylvania boarding school cemetery first appeared on Native Sun News Today.

Tags: Top News