Healing the disconnect: Penobscot Indian Nation collaboration restores Maine sea-run fish habitat

Although the river’s salmon and other migratory fish have encountered numerous challenges, including polluted waters and rising ocean temperatures, none have been as detrimental as the aging hydro dams that prevent sea-run fish from accessing vital spawning habitats.

PENOBSCOT INDIAN NATION — Indigenous communities, like many minority and low-income communities, consistently confronted with barriers to environmental justice and food sovereignty, have worked to circumvent injustice by collaborating with environmental organizations, local, state, and federal agencies, and ecological and scientific consultants. The process of cooperation has helped to create pathways to indigenous land sovereignty and food security. A high level of cooperative action is essential when adequate responses from government agencies to tribal environmental and health challenges are needed for positive change to occur. Climate-related events such as melting glaciers, decades long droughts, frequent floods, and massive storm systems combine with overdevelopment and under regulated pollution to create catastrophic, globally pervasive effects on environmental and human health (The Nature Conservancy, 2018). This is particularly devastating to vulnerable and systemically marginalized communities. Droughts cause contaminants to become more concentrated over time, while wind and rain cause pollutants to spread further from the initial source, devastating wetland and riverine ecosystems and resulting in further climate chaos (Choudhury, 2022; Government of Canada, 2016). The spread of toxic industrial and radioactive waste and its associated chemical tailings, agricultural runoff and methane from factory farming, heavy metals such as barium, mercury and lead, oil and chemical spills from production, transport, and storage facility accidents or faulty equipment, and airborne pollutants such as greenhouse gasses, has inundated the air, water, and land (Hayes & Faber, July 2021). Additionally, the human demand for energy has not only contributed to pollution and climate change but has significantly impacted wildlife populations, on which indigenous tribes traditionally and continually rely for sustenance. Conservation scientists understand what indigenous peoples have known for thousands of years, that rivers are more than just a means to an end, that water is life.

The Disconnect

Traditionally, indigenous riverine peoples depended upon riparian flora and fauna for food, transportation, shelter, clothing, and livelihoods, but were cut off from their traditional economies. Cultural and spiritual traditions, which grew around rivers and the plants and animals that the rivers support, were disconnected from the places of their origins (Fisher, 2010; Griffin, 1996). Initially, colonizers viewed river systems in terms of their own survival but the dynamic changed as time passed and rivers became more of a means for economic growth, transport of people and goods, energy production, recreation, and industrial waste disposal than for sustenance (Shiva, 2015; Fisher, 2010). For thousands of years the Penobscot traveled the waterways and depended on river trout, salmon, herring, other sea-run fish, a variety of aquatic and marine life, and non-aquatic flora and fauna in the riverine ecosystem. The connection to the river and its fish and wildlife were interwoven with the culture. Penobscot families adopted the names of fish and animals that thrived in the lush river habitat.

Continual and successful struggle against the allotment process since 1912 preserved Penobscot Indian Nation (PIN) lands totaling 154,600 acres as of 1984 (NLAP, 2023, March 17), however, the timber and, later, the paper industries decimated large swaths of unbroken forests in Maine, much of it around water sources feeding the Penobscot River. (The Maine Boomhouses, 2023). In addition, land taken for agriculture and other industries had an extensive negative impact on the local ecology as well as the livelihoods of indigenous riverine communities (Fisher, 2010; Griffin, 1996). Entire generations of Penobscot growing up in the 20th century were denied the deep connection to land and water that their ancestors had enjoyed.

Rise of Hydropower

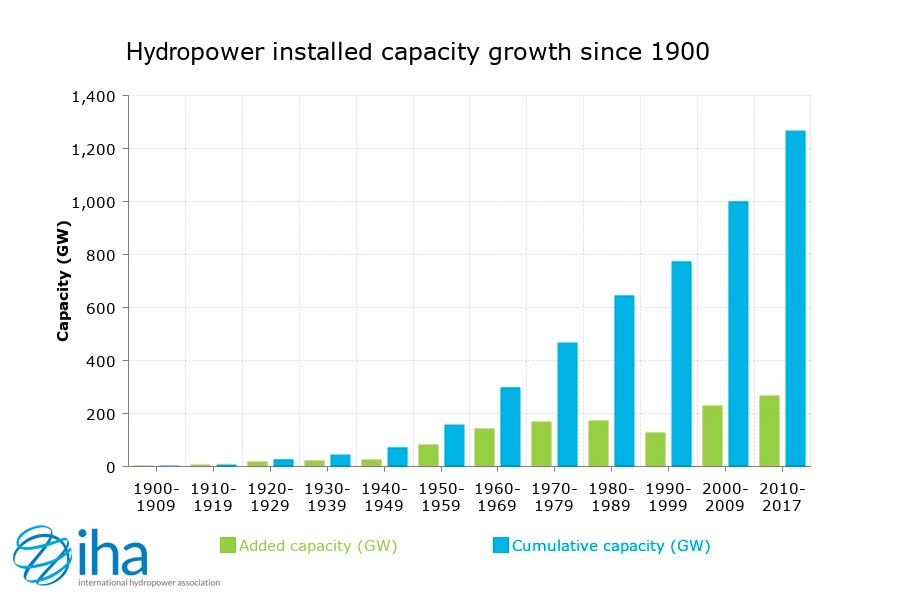

From the 1940s through the 1970s, the energy demands of a growing population and a drastic upward swing in industrial growth resulted in an exponential increase in the number of dams built in the United States to create hydroelectric power, as shown in the International Hydropower Association chart below (IHA, 2022).

Natural river systems and watersheds, long appropriated from traditional native lands for agriculture, logging, textile, paper, timber and other industries, were later leased to hydroelectric companies to power growing towns (USBR, 2011). These huge hydroelectric dams divert or greatly diminish the natural flow of water, putting long term environmental pressures on fragile riparian and estuary ecosystems. Rivers, tributaries, streams, ponds, lakes, marshes, coastal deltas and estuaries, fens, bogs, and swamps, which once provided the biodiversity necessary for the survival of animal and plant species, as well as humans, became fodder for an increasingly energy-dependent economy (Shiva 2015; Fisher, 2010; Shiva, 2008; Griffin, 1996).

Impacts of Hydroelectric Power on Riparian Ecosystems

The thirst for electrical power for towns and the industries around which they grew brought the advent of numerous hydroelectric dams and utility projects throughout the 20th century. Railroads, followed by an ever expanding system of highways, crossed the landscape, further cutting off the flow of natural water sources, erasing ecosystems, and encroaching on wildlife, while further severing traditional connections between indigenous peoples and the river. Disputes were commonplace, but nothing was done to resolve the concerns of the displaced, disenfranchised indigenous population (Fisher, 2010; Griffin, 1996).

Decline of Riverine Species: Red List and The Green Status of Species Recovery

The benefit of jobs and power production began to wane in the light of ecological deterioration of these once flowing, once prolific, natural rivers and their tributaries. Many fish populations began to dwindle because of pollutants (Foley et al. 2021), mutations appeared, (Dvorsky, 2016; Reid et al, 2016), and some species of aquatic life began to disappear entirely. (Reddy, 2018).

The Atlantic killifish thrive in the polluted estuaries of the Eastern US seaboard and have genetically evolved to be 8000 times more resilient to lethal levels of pollution than other fish. Researchers at UC Davis sequenced genomes of 384 Atlantic killifish from New Bedford Harbor in Massachusetts, Newark Bay in New Jersey, the Bridgeport area of Connecticut, and the Elizabeth River in Virginia, contaminated since the 1950s – 60s by industrial toxins such as dioxins, heavy metals, and hydrocarbons (Reid et al., 2016). The scientists found that killifish have a higher level of nucleotide diversity than other vertebrates (Reid et al., 2016). Furthermore, killifish are a prey species, often consumed by migratory birds and riverine species (Dvorsky, 2016), which can be consumed by humans and pets.

Unlike the genetic variation associated with plants, insects, and bacteria, most animals possess highly specialized genetic blueprints, causing any rapid mutation to be more of a hindrance than a benefit, a failed attempt to adapt to environmental stressors (Dvorsky, 2016). Because evolution is generally a very slow process, genetic response to rapid, anthropocentric changes to the environment is not possible for most vertebrates, which is why so many fish die in polluted waters, and survivors often leave in search of more habitable surroundings.

Extreme or sudden environmental, climate-related, human-caused changes resulting in rapid genetic mutation and subsequent death in most vertebrate species sparked a need for more information about the species at risk

In 1964, the International Union for Conservation of Nature established a Red List of Threatened Species to provide comprehensive global information on the status of risk extinction for animal, fungus, and plant species. The Green Status of Species Recovery evolved from Red List data as an assessment tool for measuring the status of species against what is considered a fully recovered baseline for each species, based on three criteria (Akçakaya et al. 2018), a species is fully recovered if it is:

- present in all parts of its range, even those that are no longer occupied but were occupied prior to major human impacts/disruption; and

- viable (i.e., not threatened with extinction) in all parts of the range; and

- performing its ecological functions in all parts of the range (IUCN 2022).

Developing data sets, identifying targets and achieving results required complex scientific knowledge, government approval, communication, and multiple cooperative stakeholders. We’re the Penobscot up to the challenge? You bet they were!

(Contact Aliyah Keuthan at kesraldancing@gmail.com)

The post Healing the disconnect: Penobscot Indian Nation collaboration restores Maine sea-run fish habitat first appeared on Native Sun News Today.