Native community backs report on Wyoming missing and murdered

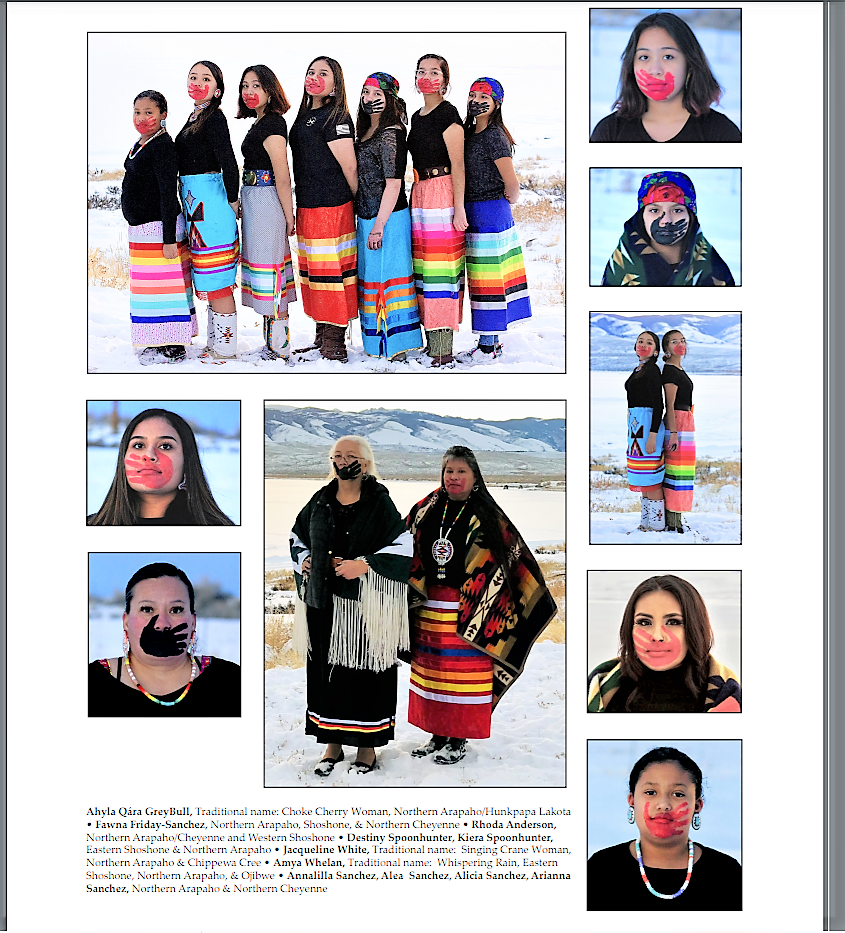

Among others, the pictured Wind River Indian Reservation area residents took part in a release of new findings and recommendations to raise awareness and obtain criminal justice system parity for tribal citizens. COURTESY / WYSAC

LARAMIE, Wyoming – Wind River Indian Reservation resident Nicole Wagon lost two of her daughters in as many years, and vowing that they would not become mere statistics, the Northern Arapaho mom joined forces with the Wyoming Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons Task Force.

“I am the mother of Jocelyn Watt and Jade Wagon. My beautiful daughters were both murdered and missing. They are why I am involved,” she told the team at the Laramie-based University of Wyoming Survey & Analysis Center, which just released a thoroughgoing report backed by the task force.

“My beautiful daughter Jocelyn Watt was murdered and found on Jan. 5, 2019 in Riverton, Wyoming of Fremont County along with her companion, Rudy Perez,” Wagon related to the team that released the report. “This remains an open case and I am hoping we will find justice for them both in the future.

“My other beautiful daughter, Jade Wagon, was reported missing on Jan. 2, 2020 to the BIA authorities. BIA found her on Jan. 21, 2020. I made them fully aware that I will not allow them to brush off her death to hypothermia and drug use. She will not be deemed as a statistic and her life with her beautiful voice still counts and matters.”

Today, one year later, the 47-page Wyoming Missing & Murdered Indigenous People Statewide Report examines and depicts what it calls “the depth and breadth of the MMIP crisis and its effects on Wyoming’s Indigenous people.”

Dated January 2020, the report to the Wyoming Division of Victim Services culminates in three recommendations for toppling barriers to justice. One of them suggested by Wagon involves boosting the cooperation of various official agencies with Native community members.

“I believe that law enforcement agencies could start by receiving a cultural sensitivity training in order to work with my Native tribal members,” she told researchers.

They concluded that a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP) advocacy or response-team position should be created to “help families navigate the reporting and investigation process from initial inquiry to final outcome.”

The advocate can serve as a communication point person, “helping to reduce the emotional burden for families of repeating details of the incident to multiple agencies,” they said.

They highlighted the need for “consistent protocols and data systems on MMIPs to inform both law enforcement and families” and for “particular attention to documenting tribal affiliation in official records, coroner reports, and vital records.”

This recommendation is supported by the U.S. Congress’ Oct. 10 passage of Savanna’s Act (Public Law No. 116-165), which mandates MMIP protocols, while requiring the federal government to update information relevant to Native citizens and improve tribal access to local, regional, state, and federal crime databases.

After talking to a number of Wind River residents and analyzing media coverage of MMIP cases, the researchers recommended raising community awareness “by educating the public (preferably by Indigenous educators) about the prevalence of MMIP, contributing risk and protective factors, and available resources.”

“If there was more education in the community about the problem, I think more people would be willing to report,” one unnamed Wind River respondent told the research team.

Native people make up less than 3 percent of Wyoming’s population, living in all 23 counties of the state but mainly in Fremont County on the Wind River Indian Reservation, home to the Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, and members of other tribes.

Indigenous persons “experience violence, homicide, sexual assault, and are reported missing at disproportionate rates relative to any other race or ethnicity in Wyoming,” the report says.

Indigenous homicide victims were 21 percent of the total homicide victims in Wyoming between 2000 and 2020. Over that 10-year span, 105 Native people (34 females, 71 males) were victims of homicide, according to the report.

Between 2010 and 2019, the homicide rate per 100,000 for Native people was 26.8, eight times higher than the homicide rate for White people. The homicide rate for Native females was 15.3 per 100,000, 6.4 times higher than the homicide rate for White females.

The inequity was not lost on Northern Arapaho, Eastern Shoshone tribal citizen Greg Day who was interviewed for the report. Day, who also has lost two children, said, “I am the voice of my two oldest kids Dawn Day and Jeff Day; law and justice should have no color. I will not give up the fight.”

The report includes details of the following summarized findings.

Between 2011 and September 2020, 710 Indigenous persons were reported missing within Wyoming’s boundaries. Some were reported missing more than once during the time period, resulting in a total of 1,254 of the missing person records. Eighty-five percent were juvenile, and 57 percent were female. They were reported missing from 22 counties in the state.

Ten percent of missing Indigenous persons are found within the same day they are reported missing, 50 percent are found within one week. One-fifth of the reported were missing for 30 or more days, which is a higher percentage than White persons (11 percent).

At the time of the report, 10 Natives were listed as missing (three females and seven males).

Only 30 percent of Native homicide victims had newspaper media coverage, as compared to 51 percent of White homicide victims. Indigenous female homicide victims had the least amount of newspaper media coverage (18 percent).

The newspaper articles for Indigenous homicide victims were more likely to contain violent language, portray the victim in a negative light, and provide less information as compared to articles about White homicide victims.

Lack of trust in law enforcement and the judicial system, no single point of contact during an investigation, and lack of information during the investigation and after the final outcome were seen as barriers in the community related to the reporting and response to MMIP.

“This is a big issue and not a lot of people are aware of it because, you know, it doesn’t affect them, but when it happens, it doesn’t affect just the family. It affects the whole community,” another unnamed Wind River resident told researchers.

Wyoming Gov. Mark Gordon convened the task force behind this report in direct response to the 2019 March for Justice sponsored by Keepers of the Fire, a student organization committed to “keeping the Native American culture alive and strong at the University of Wyoming,” the authors note.

They recalled that family members who lost loved ones and advocates shared their stories during the event to raise awareness of the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Wyoming.

While grieving, Wagon exemplifies their resolve to obtain equal rights to justice.

“It’s traumatic to bury your children before their time. Their lives have been taken by others and it’s not okay,” she said.

Report authors recognized Savanna’s Act as “an important first step,” concluding their document with these words: “Sadly, these findings are not unique to Wyoming. As seen in other states, missing and murdered Indigenous people are not geographically bound to tribal lands. They are present in urban centers, rural areas, and all places in between.

“The pervasiveness of the problem suggests that the MMIP crisis is systemic and can best be addressed using all the federal, state, and local, resources available in coordination with tribal communities.”

Signing the paper were Emily A. Grant, PhD.; Associate Research Scientist Lena Dechert, BA/BS; Assistant Project Manager Laurel Wimbish, MA, Senior Research Scientist; and Andria Blackwood, PhD., Associate Research Scientist. They thanked (Northern Arapaho, Hunkpapa Lakota Lynnette Grey Bull for the report’s cover design.

Grey Bull, director of Not Our Native Daughters, said she just hopes Wind River’s young people “know we’re advocating for them, to protect them, and work to change the data and culture, so we would not be the most stalked, raped, murdered, and sexually assaulted people – compared to other races in our nation.”

(Contact Talli Nauman at talli.nauman@gmail.net)

The post Native community backs report on Wyoming missing and murdered first appeared on Native Sun News Today.