Relative of Wounded Knee gun inventor apologizes

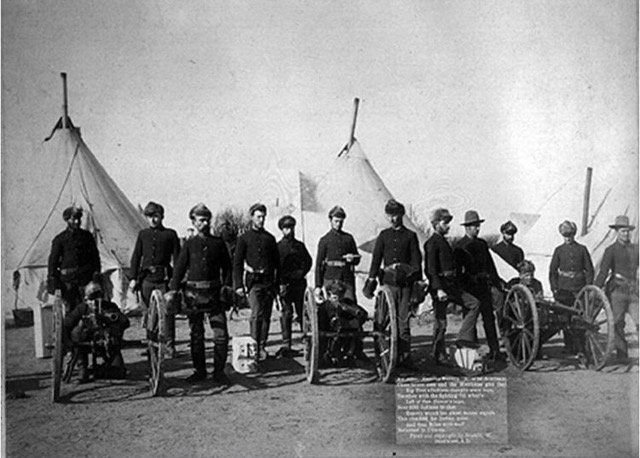

19th. Century Calvary soldiers pose with Hotchkiss guns like those used at the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890 to murder hundreds of mostly unarmed Lakota men, women, and children. (photo courtesy of Jeffrey Hotchkiss)

PORTLAND ME – Jeffrey Hotchkiss of Portland, Maine, learned in 2009 that his relative invented the Hotchkiss Mountain Gun that was horribly effective in killing hundreds of mostly unarmed Lakota men, women, and children at the Wounded Knee Massacre on December 29, 1890. The shame and guilt of that knowledge has motivated him to learn everything he can learn about Native American history (including Wounded Knee history) in order to become an effective advocate for justice for Native Americans.

According to Hotchkiss, “It’s been a long and often strange, often agonizing, ultimately wonderful trip.” He describes the self-examination and inner work required for the journey as “wicked painful,” although his report of that pain is voiced matter-of-factly with no self-pity or complaint.

Jeffrey Hotchkiss was born in Vermont and grew up on a “Vermont dirt road.” His family’s cultural heritage is “mostly English.” His ancestor, Samuel Hotchkiss, was the first Hotchkiss to reach the Americas arriving in Connecticut in 1632.

In 2005, after 25 years in the Information Technology (IT) field, Hotchkiss shifted his focus to explore holistic mind/body integration both as a personal healing pathway and as a new career field. He says, “I got in touch with my body and the ground under my feet. …Earth has a memory of the people who came before.”

Hotchkiss became licensed as an Emergency Medical Technician and reports, “(I) adventured on an ambulance partly as a way of rescuing myself, and (with historical research) became more and more convinced that European society had taken a horribly wrong turn somewhere back in time that caused us to commit global genocide in order to advance an inhuman and inhumane way of living …”

In 2009, by chance, he saw a YouTube video explaining the revolutionary-for-its-time workings of the Hotchkiss Mountain Gun, a rifled light cannon with a firing rate of four or five 1.65-inch shells a minute, deadly accurate up to a mile away. The video narrator explained how four Hotchkiss guns efficiently killed hundreds of Lakota men, women and children at the Wounded Knee massacre more than a century ago.

Of that moment Hotchkiss says, “Everything stopped. Piercing guilt consumed me. A member of my family had done bloody wrong to a whole nation. …I felt I had inherited a blood debt. It demanded to be honored. …

“I started to read everything I could get my hands on about the Wounded Knee Massacre and the use of my (relative’s) weapon – online, in books, and in correspondence with libraries, genealogists and military archives.”

Hotchkiss studied the work of Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Braveheart (Hunkpapa Lakota), a descendant of a Wounded Knee survivor, who developed the theory of historical trauma, later called intergenerational trauma, and documented its effects. Hotchkiss says, “It was very clear from (Braveheart’s) work that today’s descendants carry strong echoes of the trauma inflicted on their ancestors.

“No matter how distressed or agonized I felt about the moral effect of this great crime rolling down to my generation, that was as nothing next to the effect on the victims and survivors. …Whole family lines among the Minneconjou and Hunkpapa Lakota were cut short. …There is no ‘fixing’ that …”

Jeffrey Hotchkiss whose relative invented the Hotchkiss Mountain Gun used to murder hundreds of Lakota at the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890 is an advocate for justice for Native Americans (photo courtesy of Jeffrey Hotchkiss)

Hotchkiss heard a Native American elder speak who said to non-natives was, “Your work is within yourselves and among yourselves.”

Hotchkiss says, “…after a couple of years of learning and praying and dreaming, I understood that I had a lot of my own contemplation and (inner healing) work to do. …

“Contemplation kept circling back to this: it’s all about the children. I read and learned about many ways the children died that day, and about some who miraculously survived. Courageous warriors rode unarmed, to and from the killing ground, taking as many children to safety as they could, until they themselves fell to the soldier’s guns. … I saw that children and innocents had been killed, not as an accident, but as a matter of policy fueled by white settlers’ fear, white politicians’ calculations and my European ancestors’ insatiable hunger for conquering peoples with darker skins and different religions.

“I entered (the decade of the 20-teens) in a moral and spiritual emergency. … I thought about traveling out to Pine Ridge in South Dakota, near where the massacre took place, but cost and doubt prevented me. What would I do? Would I make a guilty white nuisance of myself? In my own neediness, would I inflict worse trauma?

“By now, it was clear my intense guilt was a stage, a beginning, a motivation. The feeling of guilt was being replaced by expanding awareness of our harmful colonial history and its present-day persistence. I was starting to learn about indigenous efforts, projects and movements that were bringing strength and hope. Instead of desperately trying to unburden myself, I could support their work – if and when invited to do so. …

“One day, I read in the newspaper that the chiefs of all the Wabanaki tribes in Maine sat down with the governor to sign a declaration of intent to form the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Its agreed-on purpose was to inquire into the effects of Maine’s failure to comply with the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 and to understand how this affected Wabanaki children and families….”

The TRC later chose the acronym REACH: Restoration-Engagement-Advocacy-Change-Healing.

Hotchkiss continued, “I watched for the opportunity to volunteer to help the TRC do its work… Two years later, I saw a notice for volunteer training – I immediately signed up.

“I found good work to do in supporting their purpose of decolonization. I unexpectedly have found community and connection with people throughout Maine and beyond. It turned out that hundreds of other people in Maine were motivated in ways similar to mine. …

“I have read and heard so many stories that were ignored or glossed over in my formal education. The true history of my ancestors’ treatment of the people native to this continent brought pain with awareness. I have met and learned from people who embody this history. The truth freed my soul to begin healing. I know now that I live on Wabanaki land, as a descendant of invaders, learning to be a respectful guest.”

Penthea Burns, REACH Co-Director, expressed in a REACH newsletter “deepest gratitude to Jeffrey for being committed to decolonization for the benefit of Indigenous peoples.”

Continuing his narrative, Hotchkiss reflects, “In December 2018, … I learned of Brad Upton, whose ancestor (Major General James W. Forsyth) had given the order the morning of December 29, 1890, to fire the guns my relative invented. We connected around our shared trauma with these horrors, and would end up becoming the best of friends … (Brad and I) are just here to say, ‘this was wrong then, it’s still wrong today, and we are here as descendants of those who did wrong, to testify to that.’”

Upton said, “Jeffrey has been involved with the Wabanaki movement for quite a few years and has been blessed to receive guidance from the grandmothers there. After he contacted me, we became kindred brothers on the path of ancestral accountability and healing and he has also benefited from the guidance of (elders on the Cheyenne River and Pine Ridge reservations). Jeffrey is a devoted historian who has helped us learn more about the lethality of his (relative’s) invention of the Hotchkiss Mountain Guns and their indiscriminate destruction at the massacre, both children, women and Lakota elders as well as the 7th. Calvary …”

In June, 2024, the HAWK 1890 (Wounded Knee) Descendants group and others gathered at Cherry Creek SD to view and discuss the final disposition of Woyuha (sacred belongings) stolen from murdered Lakota in the immediate aftermath of the 1890 massacre. For more than a century the belongings had been in the possession of the Founders Museum in Barre, Massachusetts, and were finally returned to Wounded Knee descendants in November, 2022.

Hotchkiss was not able to attend the Cherry Creek gathering as he had hoped, but sent a letter to Marlis Afraid of Hawk, one of the Cheyenne River Lakota elders active in the HAWK 1890 group. The letter was addressed “To all descendants of victims and survivors of the Wounded Knee Massacre; and to all Lakota people…”

After briefly describing the events of the Wounded Knee massacre, the letter concluded, “It was a brutal, shameful act of mass murder. I personally and deeply apologize to the Lakota people for the Hotchkiss Mountain Guns that murdered their beloved relations. I invite all who share my family name to join me, in apology and humble service to healing. Jeffrey Hotchkiss, Portland, Maine, on the lands of the Wabanaki.”

Hotchkiss noted, “I harbor no expectations of forgiveness or reconciliation to relieve white guilt. It is not my place to set a timetable for healing, or to assert that I’ve met its preconditions. By choosing to acknowledge my ancestor’s roles in this historic atrocity, I simply make a lifetime commitment to be present with that awareness and to act with integrity when invited or asked. … Public acknowledgement of the truth can release great energy for healing and change. May that acknowledgement also finally arrive for the descendants of the Wounded Knee Massacre.”

Hotchkiss said he looks forward to a time when he can visit the Cheyenne River Lakota Reservation in South Dakota. In the meantime, he actively advocates for the Remove the Stain Act which would rescind the Medals of Honor given to twenty U.S. Calvary soldiers who were at Wounded Knee. He also actively advocates for justice for Native American children who died in government boarding schools as well as survivors of boarding schools.

To other non-natives Hotchkiss would say, “Listen to the voices of the (Native) people, learn, reflect, uproot mistaken and harmful ideas, and avoid the reflex to defend and rationalize. Curb the impulse to be a ‘white savior.’”

When asked to comment on Hotchkiss’ letter of apology, Marlis Afraid of Hawk simply said, “This is the time to come all together as ONE. …It is now a time of healing on both sides. Jesus prayed as he was dying on the cross, “Father, forgive them for they do not know what they do.’”

(Contact Grace Terry at graceterrywilliams@gmail.com)

#####

SOURCES: Personal interviews and correspondence with Marlis Afraid of Hawk, Jeffrey Hotchkiss, Brad Upton

The post Relative of Wounded Knee gun inventor apologizes first appeared on Native Sun News Today.