Santee Sioux ‘We were meant to be here’

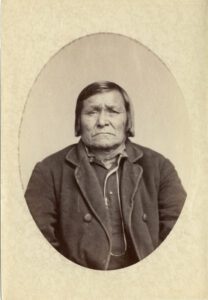

Husasa Red Legs Santee Sioux Chief and Minister

As told by Jim James, Santee Sioux Tribe

As explained in Parts one and two of this account, the Santee Sioux after an unsuccessful uprising against the U.S. Military and settlers in Minnesota, 1862 were forcibly relocated to Crow Creek, South Dakota in 1863. The living circumstances were dreadful, and many tribal members died because of sickness, disease, and starvation.

Due to a typo in the previous article, it must be clarified that 38 (rather than 36 as stated there) Santee Sioux warriors were hanged by the U.S. Military for their part in the uprising. James recounted an especially horrible circumstance during that gruesome event. The rope broke when one warrior was hanged and he survived, only to be brought back and hung a second time.

Finally, in 1867, they were once again relocated – to Nebraska where four townships had been set aside for them. This time, they were taken overland by the U.S. Military. The land was west of the present town of Niobrara, Nebraska, near a river of the same name.

Because of negative politics invoked by the whites involved with the Santee Sioux uprising some of that land was taken from them. Finally, in 1871 an Executive Order by President Arthur established the exterior boundaries of the current Santee Sioux Reservation. (Under the U.S. Constitution the U.S. President has that power. What many Tribes do not understand is that the President also has the authority to undo such an act, although that has not been done before.)

The current Santee Sioux Reservation includes five townships encompassing an area of approximately twelve by twenty miles, about 100,000 acres. However, in 1885, the U.S. government opened the boundaries enabling white homesteaders to get land grants on the Reservation and all, but a few thousand acres were then lost.

Only three thousand acres of tribal land remains, and two thousand acres of allotted land are in individual tribal ownership as authorized by the 1888 Allotment Act.

Protestant missionaries had worked hard to alleviate the suffering of Santee Dakota during the years after their unsuccessful rebellion of 1862, becoming extremely influential and highly regarded by the Santee people. Several prominent tribal members such as Husasa (Red Legs) and his son, Mahpiya Heyagamani who took the name of Garwin Whipple, were strong Christian advocates. Garwin’s’ son, Henry became an ordained minister and now Jim James, his grandson, is also a strong Christian, singer of gospel songs translated to the Dakota dialect.

As Jim James explain, his ancestors including Husasa and other Dakota who had converted to Christianity, quickly went to work on the final remnants of their once vast homeland, building churches and schools to pursue their new beliefs. Those churches became the center points for activities on the new Reservation. That included politics when a Tribal Council, under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (IRA) replaced the Chiefs to govern the Dakota.

By the turn of the 20th century, the Santee Sioux Reservation was divided into five districts. Two churches were vying for dominance on the Reservation, the Episcopalians, and Presbyterians each dominating and claiming districts which included Blessed Redeemer (Howe Creek District); Hobu; Bazille Creek and the OMMS church. Those church districts later became the basis of the IRA government electoral districts.

The mother church OMMS, eligible for historic funding, was completely restored in 1985, greatly appreciated by the Santee Sioux community.

Having grown up at Santee and after distinguished service in the Vietnam War era, Jim James returned. He started working as a Tribal Planner and Community Action Program Director employed by Tribal Chairman David Frazier, whom he much admired. Amazingly Frazier led the Tribe from 1936 to 1971 at great personal sacrifice. During that same time, Lloyd James (Jim’s father) was the Tribal Secretary. Then, tribal officials served without pay, a Christian and tribal concept of ‘service to others.’

As James noted, the Tribal Constitution was amended in 1980 which is when elected tribal officials began receiving compensation, in violation of old-time tradition. “That threw the Christian and tribal concepts of service out the door. Bad move, in my opinion,” James concluded. “That was very tricky business, the people were fooled by small print,” he added.

In the early 1970’s, due to new federal funding opportunities, the Santee Sioux Tribe began a period of recovery, Jim James, the architect of many new projects. To celebrate a century of returning to their traditional area, the Tribe commissioned a well-known artist to paint murals in the newly built community center to commemorate the tribal journey from Crow Creek. As far as Jim knows, those still exist, a reminder to contemporary Santee of the hardships and suffering endured by their forbearers.

Every Indian Nation in America has experienced similar tragedy at the hands of the white invaders. What is remarkable about all such stories is that many (but not all) Tribes have survivors who still know and acknowledge these histories.

“It is important to know the past so as not to let it happen again,” James reminds. “Thank you Native Sun News Today for accommodating the Santee story.”

Wiping out the dark-skinned people of America failed. It was not for lack of trying on the invaders part. But native and dark-skinned people are resilient and strong. As Kirk Dickerson at NSNT says “We are meant to be here.”

(Contact Clara Caufield at 2ndcheyennevoice@gmail.com)

The post Santee Sioux ‘We were meant to be here’ first appeared on Native Sun News Today.