The land, it was always about the land

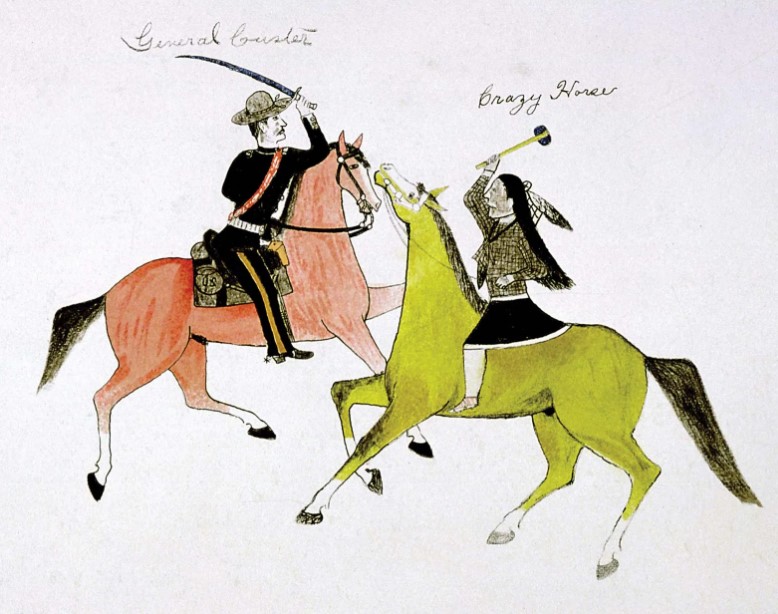

Lieut. Col. George Custer and Crazy Horse fighting at the Battle of the Little Bighorn by the artist Kills Two.

“Look for worms, at this distance the horse herd will look like worms on the grass,” said one of the Crow scouts as day was barely breaking on the morning of June 25, 1876. The scouts were trying to get Second Lieutenant Charles Varnum, Custer’s head of scouts, to see the big village strung out along the Little Bighorn River fifteen miles away, in what is now south-central Montana. Smoke from early morning cooking fires the Lakota and Cheyenne women were tending was visible in the valley. But Varnum could not see the huge pony herd grazing in the prairie to the west of the river.

Maybe five miles further back, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and his Seventh Cavalry were catching a few hours of sleep, having ridden half the night. Custer had planned to use this day to get a little closer to the village, give him and his men a chance to rest, and gather detailed information about the village he was planning to attack the following day.

Black Elk would later become a famous Lakota holy man. But today, he was a twelve year old boy….. “My father”, he said, ” woke me at daybreak and told me to go with him to take our horses out to graze. Some of us boys watched our horses together until the sun was straight above and it was getting very hot. Then we thought we would go swimming, and my cousin said he would stay with our horses until we got back. I did not feel well; I felt queer. It seemed that something terrible was going to happen. But I went with the boys anyway.”

The Crow scouts and Varnum rode up with the news that the soldiers had been spotted by some Indians. No longer could Custer count on being able to surprise the village and since he was certain the Lakota and Cheyenne would, to save the women and children, flee if they had a chance, he decided to change his plans and attack without the additional days’ rest and reconnaissance.

It was hot, the sun blazing overhead, but the Little Bighorn River [the Greasy Grass to the Lakota] ran cool and clear. Men, women, children, and little bare babies were all swimming in the shaded river. “Many people were in the water now and many of the women were out west of the village digging turnips”, noted Black Elk. “We had been in the water quite a while when my cousin came down there with the horses to give them a drink. Just then we heard the crier shouting in the Hunkpapa camp [the southern end of the village, the first to bear the brunt of the Seventh Cavalry’s attack], ‘the chargers are coming. They are charging!!” Women were screaming for their children, children were screaming for their mothers. Men were rushing to get their horses and weapons. Everywhere was dust and noise and confusion.

How did we get to this point? Why was the United States Army attacking a village of Lakota and Cheyenne people who were simply engaged in the business of living? Why, as one author phrased the question, was the United States embarked on an “…..unprovoked military invasion of an independent nation that already happened to exist within what came to be declared the United States”?

The immediate cause in this case, was that gold had been discovered in the Black Hills in 1874 and white people wanted the gold. The fact that the Black Hills were Lakota land, reserved by them in the Treaty of 1868 was seen by the federal government not as a legal right to be upheld or a moral obligation to live up to, but as a political problem they needed to deal with. General William Tecumseh Sherman, the famous Union Civil War general, and now head of President Grant’s War Department, favored if necessary, the “extermination of them, every man, woman, and child”. He made his position clear on how he thought the ‘Indian problem’ should be handled when he told General Sheridan, “the more Indians we kill this year, the less we’ll have to kill next year.” And Sheridan, who commanded the district of the army that oversaw the Dakota Territory is famous for having said, “the only good Indians I ever saw were dead.”

Since there was no honest or legal way to take the Black Hills away from the Lakota, [who refused to sell land they saw as sacred], the U.S. government concocted a story about the Indians killing white people in the area…….the ‘area’ mind you, part of their own reservation, to say nothing of the fact that the story itself had little or no basis in fact. Having thus documented and justified in their own eyes the need, the Grant administration issued an order requiring all Indians to report to their agencies by the first of January, 1876, or be declared ‘hostiles’ and be brought in by force.

But the bigger cause, was, as it had been since white people first came to this continent, ‘the land’. It was always about the land. Just as they wanted the gold, white people wanted the native peoples land. The only question was how the land would be acquired. In 1792, the views of then President George Washington and N. Carolina senator Benjamin Hawkins, over how to dispossess the Indians of the ‘newly acquired’ land north and west of the Ohio River [Northwest Territory], serves as an example of the two prevailing thoughts on the matter.

Whereas Washington wanted the nation to create a permanent standing army and use it to force the Shawnee and Delaware people to leave by making war on them, as it was referred to at that time, Hawkins felt like this was unethical. He argued in favor of seeing if the land could be bought, and at a fair price. Hawkins’ long term goal was to hopefully persuade the Indians to adopt European farming practices and to assimilate them into mainstream society. Again, though there was debate about how the land would be ‘acquired’, there was no debate in the minds of white people that the land WOULD be acquired. In his later years, long after he had stopped fighting the white people, the Lakota leader, Red Cloud was quoted as saying, “the white man made us many promises, but he only kept one of them. He promised to take our land, and he did.”

When Half Yellow Face, one of Custer’s Crow scouts, heard Custer’s plan to divide his troops into three groups, he argued with him, saying there were too many Lakota and Cheyenne in the village and they should keep their forces together if they were to stand any chance at all. He began to prepare himself for battle and said to Custer, “….you and I are going home today, and by a trail that is strange to us both.”

Maybe it was the family he grew up in, Custer was the middle child and as one author put it, “he was loved, encouraged, and admired by his parents and all of his siblings”; but whatever the reasons, by the time the Civil War ended, he had earned a reputation for courage, fearlessness and supreme confidence. An excellent horseman, more than once he led Union cavalry forces into battle, engaging the enemy before the rest of his troops had even caught up with him.

Crazy Horse, famous for his determination to defend his peoples right to live their lives as free people, was also fearless. The story is told that one day, as boys, he and his younger brother Little Hawk were out tending to the families’ horse herd. Picking chokecherries along a brushy creek, they came up on a grizzly bear. The scent of the bear scared the horses, all but one of which ran off before Crazy Horse could grab one of them. He told his little brother to climb a nearby tree, while he jumped on the back of the remaining horse, which took off across the prairie after the other horses. Finally calming the horse down and turning it around, he urged the horse into a dead run and charged the bear, which at the last second, ran away.

As a young man, Crazy Horse, seeking spiritual power through a vision quest, was ’told’ that he could not be killed in battle as long as he remained humble and only thought of ’the people’ and not himself. A Crow warrior once jokingly said that his people [who were regularly fighting the Lakota over hunting grounds as well as for honor] knew Crazy Horse better than did his own people because they saw more of him then his fellow Lakota did since he, like Custer, was always out in front.

But unlike Custer, whose life was one in which pretty much everything turned out fine for him [until this day, that is], Crazy Horse’s life was one that had more than its share of tragedy. His mother committed suicide when he was a young boy, his brother Little Hawk was killed by miners in the Black Hills, and his only child, They Are Afraid of Her, died when she was but a little girl, possibly from a ‘white man’s disease’.

There are fascinating stories about many of the people there that day as well as fascinating questions about the battle itself……how to account for Sitting Bull’s vision during a sun dance not two weeks previous, of soldiers falling upside down from the sky into the Lakota camp?

Custer and his two officers, Major Marcus Reno and Captain Frederick Benteen, the three of whom didn’t like each other; was this a factor in Benteen not coming to Custer’s aid? The Lakota warrior Gall lost his two wives and three daughters in the first assault by Reno’s troops. He said later that he was so angry he fought the rest of the battle with nothing but a tomahawk. Why did Custer divide his forces, could he, as Pretty White Buffalo Woman said, have succeeded in routing the village had he not? How was it possible for Crazy Horse to twice, at a dead run, ride his pony through the soldier’s skirmish line, and not get hit by all the bullets being fired at him?

Though not all of the over six hundred men who comprised the Seventh Cavalry that day died, all those under Custer’s direct command did. The nation was aghast, having just finished celebrating its one hundred year anniversary, it had now to make sense of how the most famous Indian fighter in the country, a Civil War hero, could have been defeated by what most white people considered a group of savages only one step out of the Stone Age.

The post The land, it was always about the land first appeared on Native Sun News Today.