Weaver of musical stories

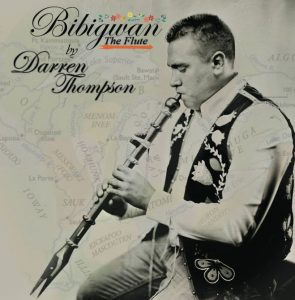

The cover photo of “Bibigwan: The Flute” is reproduced from a wet plate ambrotype photograph made by Shane Balkowitsch, using a revived technique Edward S. Curtis employed to document 19th Century American Indian life. Photo COURTESY / Darren Thompson

RAPID CITY — Flautist Darren Thompson’s Ojibway and Tohono O’odham roots may be traced to the Great Lakes and the Sonoran Desert, yet the Black Hills holds a special place in his life, prompting him to record and announce his most recent music release right here in Lakota Territory.

“Bibigwan: The Flute” is a collection of 15 native flute pieces he rescued, composed, and performed in collaboration with Lakota musicians Sequoia Crosswhite and Reuben Fasthorse. It expands upon the realm of musical storytelling that the acclaimed artist entered with his 2009 first release “Song of Flower” and widened with its 2015 follow-up “Between Earth and Sky: Native American Flute Music Recorded in the Black Hills”.

Of the continuum, he explains, “I try to teach people about native contributions – past, present, and future. That’s why I started my craft of flute playing.”

The exercise, spanning more than a decade since he taught himself the craft, has forged “part of my identity as a weaver of musical stories,” he told the Native Sun News Today in an exclusive interview heralding his latest studio recordings.

As the first moon phase of 2020 approached, Thompson looked back over the months of the previous calendar year to one of the most powerful storytelling lessons he recalls: spring spearfishing for walleye by night torchlight, the time-honored subsistence activity that gave his Lac du Flambeau Indian Reservation its French name.

The initial two weeks of the Wisconsin state fishing season are legally protected for tribal members only, despite oft-boisterous complaints from sport-for-profit interests competing to claim higher bag limits and more tourism dollars. The safeguard is thanks to treaties negotiated by his ancestors, Thompson notes.

“It’s breathtaking just to know that the generations before you felt it was so important that they wanted you to have the right,” he observed.

The experience swayed him to branch out from flute interpretations into research and writing a book on Ojibway political history from 1720 French-voyageur contact to the present. Among other things, it aims to document the source of the “misunderstanding” over natives’ priority fishing rights, he said.

In order for the state of Wisconsin to gain recognition from the original inhabitants, negotiators agreed to treaty language in which “the tradeoff was as long as we could hunt, fish and gather for ever and ever and ever and ever,” he said.

He won a research grant from Crazy Horse Memorial back in Lakota Territory to underwrite the costs of travel to the National Archives in College Park, Md.

Thompson also accepted a role as the Assistant Director of the Minnesota Indigenous Business Alliance this winter, to support indigenous entrepreneurs, businesses, and companies, both in and outside the state.

The multi-tasking is unlikely to interrupt his musical trajectory. One of the things he enjoyed most in 2019 was becoming “the first member of my tribe to perform at the Smithsonian Institution.”

Next thing you know, he was performing at the Pocahontas Reframed “Storytellers” Film Festival in Richmond, Va. Filmgoers were captivated by his demonstration of the kind of flutes they heard in movie soundtracks featured at screenings, he said.

A trick to storytelling with the flute is that it’s “not intimidating,” he reflected. “Walls are let down.” Listeners know they are “not going to have to deal with the angry Indian,” he noted.

He’s already planning his next studio release. He said he hopes it will incorporate guitar, violin and cello. While his sons are both in symphony orchestra, he confesses, “I don’t play any other instruments; I don’t even read music.”

No problem, says Rick VanNess, the Hill City sound engineer who recorded Thompson’s second and third releases. “He’s very much a collaborator.”

Thompson taught Fasthorse the tuning to play a song on Bibigwan called “The Photograph”, sharing a secret he had ferreted out. “You can’t buy this tuning on Internet, so you have to know someone, or someone who knows someone, to learn,” Thompson said.

He invited Crosswhite to play guitar to his birch flute on his favorite Bibigwan title, “Spirit Song”.

On the recordings, the titles frame the stories, and the instruments tell the rest. The names give listeners pretty good cues, leaving just enough to the imagination with selections such as: “Creation Song”, Zuni Sunrise Song”, “Hopi Flute Improvisation”, Eagle Whistle Song”, “We Will Continue”, “Improvisation in G Minor”, “Night Traveler”, “Into the Sunrise”, “The Woodpecker Song”, “Grand Medicine”, “The 7th Generation”, “Four Direction”, and “The Next 7 Generations”.

Thompson has assured the accessibility of the 52 minutes of music by making them available as individual downloads or as sets on a range of media outlets, including his official website darrenthompson.net/, www.youtube.com/, www.apple.com/itunes/, www.spotify.com/us/, play.google.com/music, and www.pandora.com/.

The recording quality is without fault, which VanNess attributes partly to Thompson’s willingness to collaborate on technical fixes. “I wish other artists could be so easy to record,” VanNess told the Native Sun News Today.

“The flute is an instrument that has so many nuances and subtle sounds that I tried my best to research the ways to capture those,” he added.

A specialist in recording acoustic music for South Dakota Public Broadcasting and live concerts, VanNess also let on that placement of the microphone and harmonious surroundings are keys to success. A full-fledged recording studio was not a requirement for these pieces, he remarked.

A storeroom, a hallway, and a prairie gully were among the settings for the work leading up to the production of Bibigwan. “I look for places that are quiet and acoustically compatible with whatever it is I’m recording,” Van Ness said. “I go to wherever. The world is my studio.”

The world is not too big a stage for Thompson, as followers know. He is currently on his way to his first show of the new year, the International Indigenous Music Summit in New Orleans on Jan. 22.

In live performances, Thompson is forthcoming about the meanings of his tunes, adding verbal explanations about the specific flutes in use and the genres of his musical arrangements.

His signature flute, carved to his specifications by Jon Norris Music & Arts, appears with him in the cover photo of Bibigwan. The instrument is decorated with the image of a crane, a significant creature in Ojibway history.

The photo is reproduced from a wet plate ambrotype photograph made by Shane Balkowitsch, one of only about 1,000 photographers in the world who have schooled themselves in reviving this technique used by Edward S. Curtis to document 19th Century American Indian life.

Curtis came to be known as the Shadow Catcher. In 2018, Calvin Grinnell Running Elk, a historian for the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Nation, held a naming ceremony for Balkowitsch at the photographer’s Bismarck, N.D. studio, giving him the same handle, which translates to Maa’ishda tehxixi Agu’Agshi, in Hidatsa.

The latter-day Shadow Catcher’s goal is to create 1,000 photos of contemporary Native Americans, using the antique process. At his present pace, he calculates that as a 20-year commitment.

(Contact Talli Nauman at talli.nauman@gmail.com)