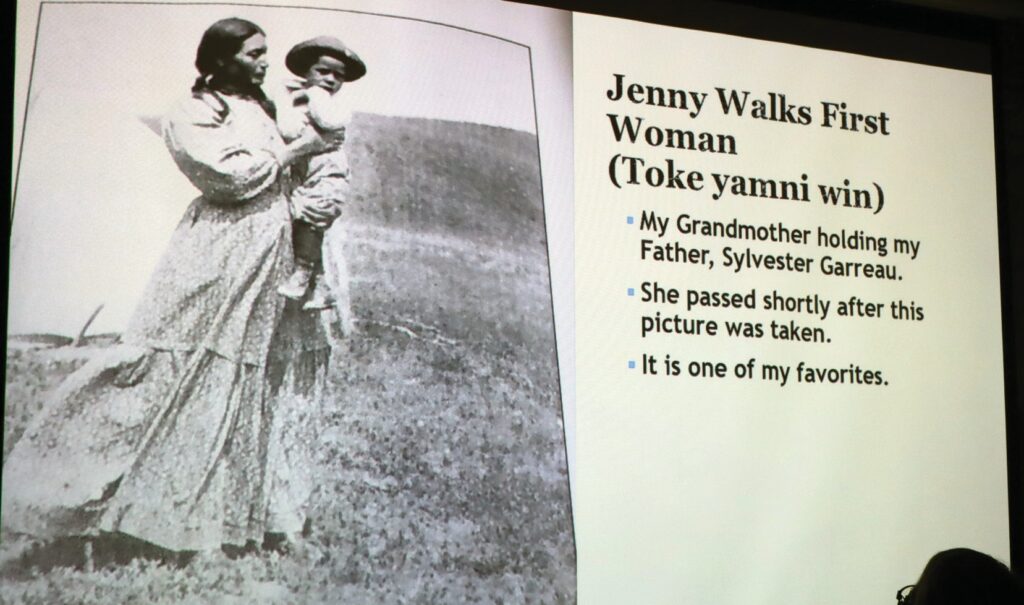

Wounded Knee survivor Jenny Walks First Woman remembered by granddaughter

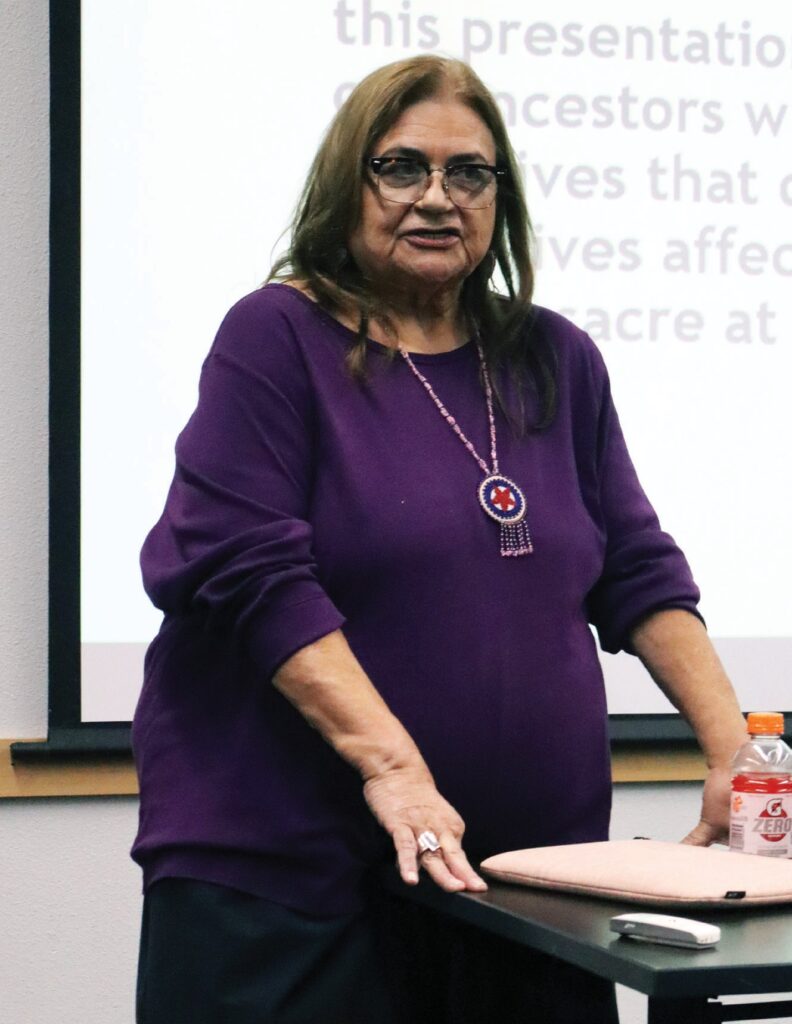

Monica Garreaux Schmidt shares the story of her grandmother Jenny Walks First Woman (Toke yamni win) during a Community Relations Commission-sponsored event at the Rapid City Library. (Photo by Marnie Cook)

RAPID CITY – December is a difficult time for the Lakota. As their non-Native neighbors are buying gifts and putting up Christmas lights, tribal members from all over the state watch the Big Foot riders make their way from Bullhead South Dakota to Wounded Knee and remember the massacre that happened there as well as the events that led to the killing of their defenseless, starving and desperate relatives.

Many Native Americans continue to suffer the legacies of loss and the trauma caused by acts of violence committed upon them, even after the last massacre. The cycle of grief has only been compounded by the retelling of the settler story which lauds the policies of removal that have devastated tribal communities. Their own stories suppressed or omitted entirely, Native children alongside their non-Native classmates have learned for more than a century that Christopher Columbus discovered America, the Pilgrims and Indians were friends and that the federal government “battled” to save the settlers from the inexplicable murderous intent of the “savage.”

Monica Garreaux Schmidt shares memories of her grandmother Jenny Walks First Woman, a survivor of the Wounded Knee Massacre. (Photo by Marnie Cook)

But by the mid-twentieth century, there was a movement to force the federal government to recognize treaties, sovereignty and the protection of Native Americans and their civil liberties. This activism manifested in many ways. Some took to occupying Alcatraz Island and Mount Rushmore, while others pursued higher education and searched for academic answers.

The grief from past tragedies persists today, but the ability to share their own stories has been a source of healing for individuals, families, and communities. Monica Garreau, from the Cheyenne River Reservation, recently recounted the story of her grandmother, who survived the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, during a Community Relations Commission-sponsored event at the Rapid City Library.

Garreau was born at Cheyenne River, attended Timber Lake High School, and graduated from Black Hills State University. After teaching for a few years, she pursued further education at Arizona State University.

“I’m so happy to be able to tell the story of my grandmother, Jenny Walks First Woman,” Garreau shared to a full house. “It’s a horrendous event that I’ll be sharing with you today,” she said matter-of-factly. “Nevertheless, I’ll be talking about the Massacre at Wounded Knee, 1890 and my grandmother was an unknowing participant or survivor of it, and she wasn’t very old.”

Garreau explained that 1890 was not a good time for Native Americans. Food and resources were scarce. “It was a really desperate time period for Native Americans. Buffalo had been hunted to near extinction by buffalo hunters who did not hunt for the meat. They were after the hides and skulls.”

Children were being placed in boarding schools, often transported far away from home. For members of the Standing Rock, Cheyenne River and Pine Ridge Reservations, the schools in Pennsylvania and Virginia were a long way from home.

Garreau explained that land was being taken by settlers while Native Americans had been removed to reservations, which were small pieces of land. “The railroad companies advertised that Indian land was for sale, with easy payments and a person could have possession within 30 days. States were offering thousands of acres for grazing and farming. It was a madhouse of sellers who were coming here.”

It was rumored that a Paiute prophet named Jack Wilson in Nevada promised through prayer that traditional lands would be returned, and the settlers would leave. “And so, this prayer became the Ghost Dance religion. Really, it is a very peaceful movement but it frightened people and it frightened probably the wrong people.” The cavalry specifically, who misunderstood the fasting and singing and tried to prohibit gatherings. The Ghost Dance spread across the Dakotas.

Sitting Bull, who had been the grand marshal at the Fourth of July parade in Bismarck, North Dakota that year, was told to cease-and-desist but he resisted. “Police were sent to his homestead, and it was in the early December morning hours that a scuffle broke out and Sitting Bull was shot and killed.” The people became afraid and so decided they needed to travel south to Cherry Creek.

Garreau’s grandmother, her husband and her two children lived along Cherry Creek and belonged to this band, a community of about 350 led by Big Foot. They too wanted to a consult respected leader about the Ghost Dance, specifically

Red Cloud who was at Pine Ridge, but they were prevented from traveling. “So, they decided they would build their fires really big and leave in the middle of the night to get to Pine Ridge.” The cavalry discovered they were gone and tracked them easily through the snow. they had already left. They were overtaken by the Seventh Cavalry just eight miles from Pine Ridge.

“My grandmother said that the cavalry was very accommodating to them the night before,” said Garreau so there was no reason to think that anything was wrong or that they were in danger. “During the night my grandmother said that she heard movement around them but didn’t suspect anything.” They had no idea they were being surrounded.

The next morning, December 29th, surrounded by cavalry, they were ordered to surrender all weapons, including knives, auls, sewing needles. “So, my grandma gathered her stuff and gave it to her husband to take to the center of the circular encampment as ordered. And when he was gone is when the shooting started. Her recollection was that the smoke was so heavy she couldn’t see anything. That smoke was created by the military’s new guns, the Hotchkiss, a revolving cannon that had not been field tested prior to the massacre.

Walks First Woman had her four-year-old daughter and a baby on her back. “People were screaming and yelling. She reached out and grabbed a horse.” It happened to be one that belonged to them and so was familiar to her. “As she got on the back of that horse, she felt something hit her back, but she didn’t stop.”

She continued her journey into the Badlands until she felt it was safe to stop. “As she had suspected the baby had been shot and was dead. So, she found some dirt and buried the baby. Then she and her little girl returned to Cherry Creek.”

Not long after their return, the little girl began having respiratory problems and passed shortly after that. “My grandma always thought that it was the heavy smoke that she breathed in on those killing fields that damaged her lungs.”

Three hundred men, women and children died that day. Garreau’s grandmother, who lost her entire first family that day, was one of the 50 people who survived. “One of them was my grandmother and one was her brother, Charlie Blue Arm. She was so amazing.”

(Contact Marnie Cook at cookm8715@gmail.com)

The post Wounded Knee survivor Jenny Walks First Woman remembered by granddaughter first appeared on Native Sun News Today.

Tags: Top News