The Santee Sioux at Crow Creek: Part II of their tragedy

Part 1 of this tribal history article described the Sioux uprising of 1862 in Minnesota, an effort to regain tribal lands which resulted in their defeat. Thirty-six of them, who were found guilty in that conflict, were then hanged by the U.S. military, the largest mass hanging in American history.

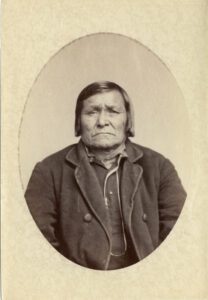

Others were reprieved, especially those who got baptized and converted to Christianity, such as Husasa.

Jim James, Santee tribal elder, former Tribal President has primarily related this history; tribal history teacher and descendent of that principal Chief Husasa (Red Legs).

After the uprising and hanging, held at Mankato, Minnesota on December 26, 1862, and the ensuing climate of hatred and revenge from the Europeans, the captured Dakota who escaped the hangman’s noose were taken from their families. They were forcibly removed by the military from Fort Snelling to Davenport, Iowa where they were imprisoned. Because of the harsh conditions and a smallpox epidemic, 120 died during those three years there.

Soon after the Santee warriors were sent to Davenport, their women, children, and elderly men from the Fort Snelling camp were loaded on two steamboats and started the journey to Crow Creek in south central South Dakota on May 4, 1863, not yet a formalized Reservation.

John P. Williamson, a Presbyterian minister accompanied the Santee. He in a letter to his mother wrote:” As they look on their Native hills for the last time, a dark cloud is crushing their hearts.”

He also wrote: 770 Santee were loaded on the first boat and 540 on the second. Another two hundred Dakota, who had been “friendlies” to the whites during the uprising were allowed to “go with the scouts” (white people).

“When 1,300 Indians were crowded like slaves on the boiler and hurricane deck, fed musty hardtack and briny pork, they had not half a chance to cook. Diseases were bred, which combined with the gumbo soil at Crow Creek (benentine or clay soil) resulting in the deaths of three hundred more Dakota within a brief time of their arrival. He concluded ‘teepees without a sick person inside were rarely found and it was a rare day when there was not a funeral.”

On June 1, 1863, 1,300 surviving members of the once mighty Santee band of Sioux found themselves in land that even the whites did not want. Droughts had left it barren, completely unsuitable for gardening or farms, even if they had had the means to do so. So different from the lush green lands they had lost.

After being imprisoned in Davenport for his role in the 1862 uprising, then converting to Christianity, Husasa was allowed to rejoin the Dakota at Crow Creek. His people were starving. The women, for example were forced to sift through animal manure, hoping to find bits or corn, etc. which could be made into soup. The Dakota were further humiliated when the women were abused by soldiers from the fort that had been built to guard the Santee, especially when rations were short, and the people were starving and sick.

Most women will resort to anything to save their children and loved ones; Jim James observed.

Husasa gained written permission from the Indian Agent in charge to take warriors on a buffalo hunt to save the Tribe. He was granted a piece of paper attesting to that, advised to keep it on his person or risk being shot by the military as a “renegade.” According to Jim James, a principal warrior and hunter was Mazadidi, a trusted confidante. His descendants are the Kitto family of Santee.

The hunt was successful, giving the Santee another reprieve.

The final installment of this horrific story will describe how the Santee were finally moved to their present-day home in Nebraska in 186, now a permanent sanctuary.

(Contact Clara Caufield at 2ndcheyennevoice@gmail.com)

The post The Santee Sioux at Crow Creek: Part II of their tragedy first appeared on Native Sun News Today.