Restoring Riverine Ecosystems and Traditional Economies

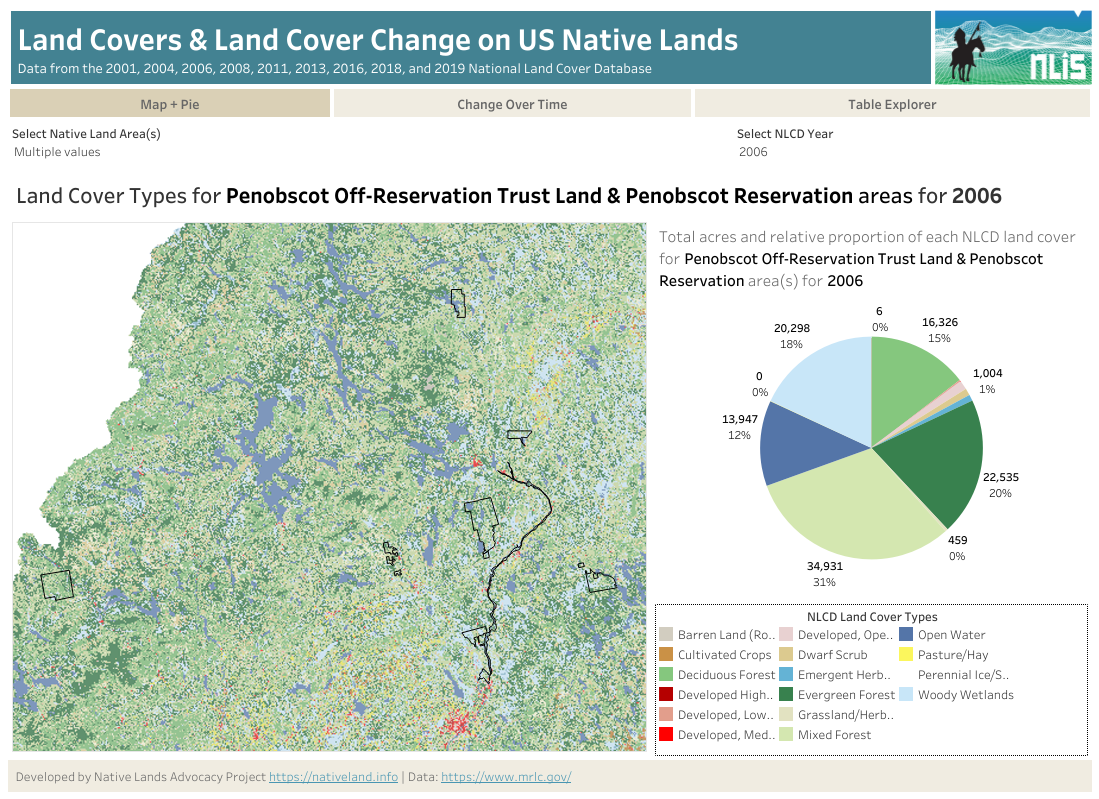

Map shows land cover types on Penobscot reservation and off-reservation trust lands. Note: The portion of the Penobscot River outlined in bold black lines is part of the Penobscot reservation

Part two of three

For decades, deleterious effects of contamination and diverting the flow of natural estuaries and riparian ecosystems led to heated legal debates over control of land and water and how to conserve and protect them. The conservation and scientific communities finally gained a foothold in the federal government, and on December 2, 1970, the United States Environmental Protection Agency, or USEPA, was formed. In the following decades, ongoing struggles over control or protection of water and aquatic ecosystems led to a dire need for cooperation between federal, state, and local government agencies, non-profit conservation organizations, and native nations throughout the US, but cooperation was a long time coming. The Penobscot Indian Nation (PIN) in Maine was among the first native nations in the coastal United States to secure protections for the flora and fauna of riparian ecosystems on and off reservation lands in an effort to restore traditional riverine economies.

Penobscot Indian Nation Embarks on Unprecedented Cooperative Journey

Partnerships were paramount to the success of the Penobscot to establish agency in the decision making process concerning the future of the Penobscot River and the native species dependent upon river habitat. The results brought a renewal of traditional livelihoods and projects working toward regeneration of habitat for fish and wildlife as well as for the future generations of indigenous Penobscot.

Reconnecting the Sea-Run

In 1999, the utility company Pennsylvania Power and Light, PPL, acquired a group of hydroelectric dams in Maine. This became PPL-Maine. The utility company approached the Penobscot Indian Nation concerning permit renewals for hydroelectric dams along the Penobscot River. The Penobscot River Restoration Trust was created out of a groundbreaking collaboration between the Penobscot Indian Nation, American Rivers, Atlantic Salmon Federation, Maine Audubon, Natural Resources Council of Maine, Trout Unlimited, the United States Department of Interior, the State of Maine and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA (TNC, 2023).

The mission of the Penobscot River Restoration Trust, was to rehabilitate 1,000 miles of habitat for endangered Atlantic salmon, sturgeon, and river herring. The framework was designed to protect the migratory habitat of eleven sea-run fish species plus the American eel after 200 years of separation between the ocean, and the main river, its tributaries and freshwater ponds. (TNC, 2023). The plan included regenerating the ecosystems upon which other riverine species depend along the Penobscot River.

Diverting Water Flow and Dismantling Dams

In 2006 The Nature Conservancy committed resources and technical assistance to the project. To achieve the goals of the Penobscot River Restoration Trust, two of the hydroelectric dams acquired by PPL-Maine had to be removed and the damaged habitat restored. Water flow also had to be diverted around a third dam. These three dams were located in the lower Penobscot River. In December 2010 the Viazie, Great Works and Howland dams were purchased by the trust. Work started in June 2012 to remove the Viezie and Great Works dams with private funding and funding from the NOAA, and was finished the following year. Work to build a natural channel bypassing the Howland dam was completed in 2015 and a lifelong dream for generations of Penobscot natives was finally realized (TNC, 2023).

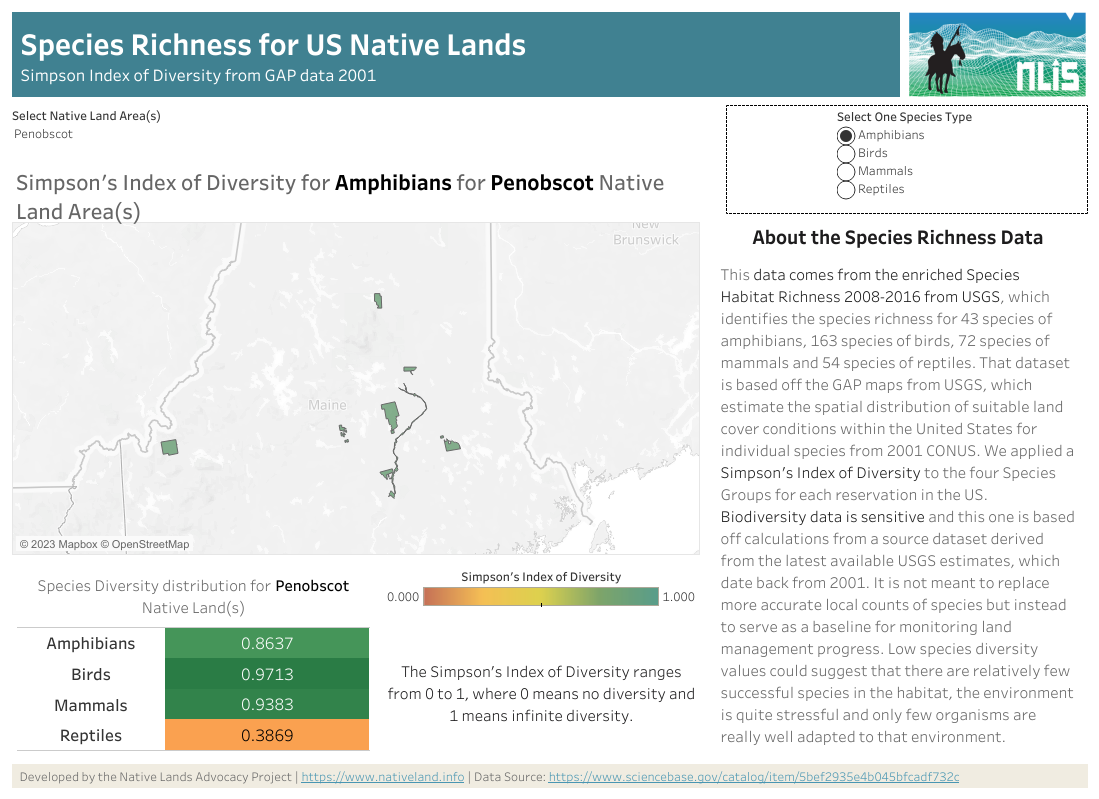

The NLIS Species Richness Dashboard shows baseline data for the Penobscot Nation reservation and trust lands from 2001, based on Simpson’s Index of Diversity. Source: public.tableau.com/shared/Z8N9YD38R?:display_count=n&:origin=viz_share_link&:embed=y

Victory Lap

David Ferris (2012, June 11), a former contributor to Forbes online magazine, wrote of the removal of the Great Works Dam:

“A ceremony is being held today to celebrate the removal of the Great Works dam, which has blocked the fish commute on the Penobscot since the 1830s. The Penobscot River, the second-longest in New England, begins below Mount Katahdin in the North Woods and ends its journey 109 miles later in Penobscot Bay.”

“Water began flowing through the Howland Dam bypass on Sept. 28 [2015] …This spring at the Milford fish lift (see video at vimeo.com/98167482) nearly 590,000 river herring were counted… 45 times more than counted in 2013. More than 1,800 American shad were also counted this spring, whereas only 20 total shad were counted in the previous 30 years combined. The new bypass at Howland Dam will allow salmon and shad to access critically important habitat in the Piscatiquis watershed, including many smaller headwaters tributaries that serve as spawning and nursery grounds. ”

Conveying more exciting news, Taylor stated,

“Even numbers of the imperiled Atlantic salmon are moving in the right direction. The 726 salmon counted this year represented a nearly threefold increase in the historic low counted in 2014.”

The NLIS data map below, shows species richness data for birds, amphibians, mammals, and reptiles on Penobscot reservation and trust lands from GAP data for 2001.The data, collected before the dam removals and associated habitat restoration projects, serves as a baseline for more recent analysis.

The collaborative dam removal and diversion process had a snowball effect. Others across the state planned or are advocating for more dam removals and fish bypass projects, such as the push to remove four additional dams in the lower Kennebec river system. (Taylor, 2023). According to Taylor, the removal of these four dams is necessary to the survival of salmon in the state of Maine.

(Contact Aliya Keuthan at kendraldancing@gmail.com)

The post Restoring Riverine Ecosystems and Traditional Economies first appeared on Native Sun News Today.