Native contributions to modern life abound

RAPID CITY—Each November, Native American Heritage Month invites reflection, recognition, and renewal. Across South Dakota, from the Black Hills to the Minnesota border, events this year blend tradition and modern expression— concerts, films, lectures, and ceremonies that speak not only to endurance but to contribution. The month is not a commemoration of the past; it is a reminder that Native nations remain vital to the nation’s present and future.

At the Crazy Horse Memorial, the Lakota Music Project will open the season with a performance uniting symphonic and Lakota musical traditions. Educational programs sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities will preserve Native languages and oral histories, while community gatherings across the state will offer opportunities for non-Native audiences to learn and engage respectfully.

Nationally,the2025theme—“Storytelling”— underscores the power of Indigenous narrative to preserve memory and transmit knowledge. “It’s about our resilience, our tenacity, and our survival,” said Justin Deegan, an Arikara, Oglala, and Hunkpapa citizen from Fort Berthold. For Standing Rock’s Ashley Jahner, it is also a time “to honor the sacrifices our elders made for us to be here today.”

Native American Heritage Month began with President George H.W. Bush’s 1990 proclamation, though the first statewide “American Indian Day” was declared in 1916, thanks to Blackfeet rider Red Fox James. Each president since has renewed the November observance—except this year, when the Trump administration declined to issue a proclamation and federal agencies like the Defense Intelligence Agency suspended internal recognition programs. Still, tribal communities, schools, and cultural centers across the country are carrying the observance forward on their own terms.

For many Native people, celebration is inseparable from remembrance. Boarding school survivors and descendants recall policies designed to erase Native identity through forced assimilation. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition counts more than 500 such schools—many run by churches under federal contract. “Our grandparents went through those schools,” said Brek Maxon of the Mandan, Arikara, and Hidatsa Nation. “Remembering our heritage reminds us of their endurance.”

That endurance now manifests in language revitalization, land reclamation, and food sovereignty movements. On the Standing Rock Reservation, Jaimie Archambault marks the season by harvesting berries for medicine. Cheyenne River’s Annie High Elk honors the month by hiking Bear Butte, a sacred site near Sturgis. “Being Native isn’t about a calendar,” she said. “It’s every day.”

The story of Indigenous America is not only one of survival—it is one of innovation that shaped global civilization. Before European contact, Native farmers had domesticated nearly two-thirds of the world’s staple crops:

• Maize (corn)

• Beans (including tepary and common varieties)

• Squash and pumpkins

• Potatoes and sweet potatoes • Tomatoes

• Peppers (chili and bell)

• Sunflowers

• Avocados

• Cacao (chocolate)

• Pineapples, strawberries, cranberries, blueberries

• Tobacco

• Cassava (manioc), quinoa, amaranth, and peanuts

None of these existed in the Old World before 1492. Together they transformed global diets and commerce, providing the caloric foundation of modern agriculture. Corn alone now feeds billions worldwide.

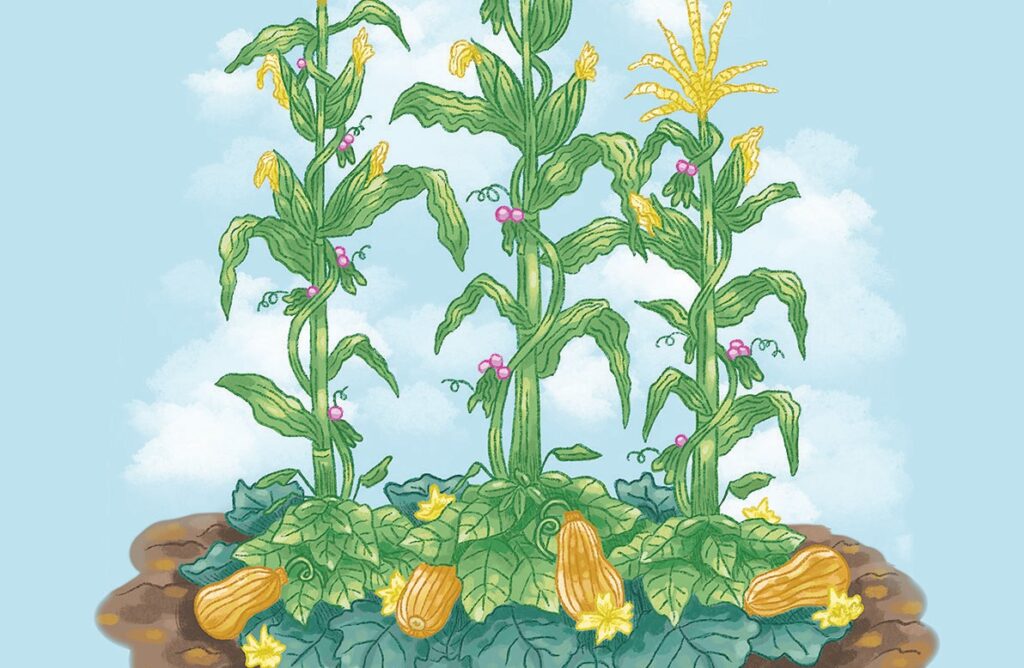

Native farmers also pioneered sustainable techniques that modern science continues to validate. The “Three Sisters” method—planting corn, beans, and squash together— formed a self-sustaining ecosystem: corn as a trellis, beans fixing nitrogen into the soil, and squash shading out weeds. Agronomists have confirmed that this polyculture yields more nutrition per acre than any single crop system, producing complete proteins and preserving soil health.

Beyond agriculture, Native innovations in engineering, astronomy, and medicine continue to influence modern research. From Mary Golda Ross, the first Native American female aerospace engineer who helped design interplanetary missions, to John Herrington, the first Native astronaut, Indigenous scientists have carried ancestral principles into the frontiers of space. Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte, the first Native woman physician, built the first private hospital on a reservation. Anthropologist Ella Cara Deloria preserved endangered languages and cultural frameworks still used by linguists today. The creative legacy of Native America extends into the arts and letters. The consummate beauty and eloquence shared by N. Scott Momaday in House Made of Dawn has yet to be matched. Authors Louise Erdrich (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe), Joy Harjo (Muscogee Nation), Angeline Boulley (Sault Ste. Marie Tribe), and Robin Wall Kimmerer (Citizen Potawatomi Nation) have reshaped contemporary American literature, weaving Indigenous worldviews into national consciousness.

In the visual arts, painters and sculptors such as Oscar Howe, Allan Houser, and Jaune Quick-to-See Smith bridged traditional form with modern abstraction, influencing generations of artists. Native artisans sustain intricate beadwork, quillwork, and star quilts—living testaments to the balance between tradition and innovation.

Politically, Native leaders have long shaped the nation’s democratic ideals. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, or Iroquois League, inspired key elements of the U.S. Constitution, including federalism and checks on power. Today, Native legislators, attorneys, and judges serve at every level of government, guiding policies on conservation, education, and sovereignty.

South Dakota’s celebrations reflect this broader story of continuity. Tribal colleges and universities are hosting forums on language revitalization and climate resilience. Schools are inviting elders to teach oral histories, ensuring the next generation learns from voices too long excluded from textbooks.

For non-Native residents, participation begins with awareness—attending a powwow, supporting Native artisans, or learning the tribal history of the land beneath one’s feet.

Native agriculture and philosophy continue to offer lessons for an ecologically strained world. Long before terms like “sustainability” and “climate adaptation” entered modern vocabulary, Indigenous nations practiced them daily—rotating crops, managing bison herds, building irrigation canals, and honoring the cycles of the earth.

Those traditions endure in efforts to restore buffalo herds on the Plains, revive heirloom seeds in community gardens, and reintroduce fire as a tool for forest renewal. Each practice affirms a worldview where humanity is part of, not master over, the natural order.

Native crops feed us, Native philosophies guide our stewardship, and Native stories remind us that all heritage is not static. It grows, like the corn grown in South Dakota, a hybrid plant that cannot survive on its own, which requires the attention and skill of people cooperating in large networks, to survive.

(James Giago Davies is an enrolled member of OST. Contact him at skindiesel@msn.com)

The post Native contributions to modern life abound first appeared on Native Sun News Today.

Tags: Top News