A forgotten generation of Lakota leadership

PINE RIDGE—Long before hashtags and viral protests, both Pine Ridge and Rosebud sent a quiet generation of Lakota leaders into the heart of federal power. They did not seize buildings for the cameras or shout into microphones. Instead, they wrote policy, crafted legislation, changed budgets and, in the process, shifted the entire relationship between tribal nations and the United States.

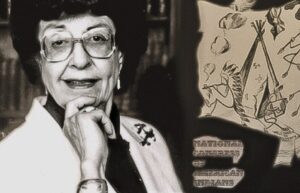

Helen Peterson

Helen Louise White — Wa-Cinn- Ya-Win-Pi-Mi, “woman to trust and depend on” — was born on the Pine Ridge Reservation in 1915. But her advocacy took her far across the country. In the late 1940s, while America congratulated itself on winning World War II, Denver’s new mayor hired her to help desegregate a deeply divided city. Peterson went door to door in Latino neighborhoods, registering voters, building coalitions, and creating the city’s first Commission on Human Relations. She pushed for fair housing and employment policies at a time when “civil rights” was still a dangerous phrase.

In 1953, urged on by Eleanor Roosevelt, Peterson moved to Washington, D.C., to rescue the struggling National Congress of American Indians. NCAI was broke, internally divided, and facing a hostile Congress bent on “termination” — dissolving tribal governments, ending federal responsibilities, and forcing Native people into full assimilation.

Peterson organized what was then the largest gathering of tribal leaders in history to oppose termination. She coordinated telegram campaigns, educated members of Congress, and helped tribes assert sovereignty at a time when that word was barely spoken in Washington.

Her diplomacy extended to the long legal struggle over the Black Hills. When the Sioux land claims case (Docket 74) was nearly lost on a weak record, it was Peterson who was asked to persuade the popular tribal attorney Ralph Case to step aside. She did it without public drama, making way for the legal team that eventually produced the landmark United States v. Sioux Nation decision in 1980. No marches. No headlines. Just quiet, decisive leadership.

Dr. Jim Wilson

James John Wilson III, “Akicita Cíkala,” grew up in the austere, agency-dominated pre-war Pine Ridge. By the 1960s, he was in Washington, D.C., running what sounds like a small office — the “Indian Desk” in President Lyndon Johnson’s Office of Economic Opportunity. In reality, he was directing the Indian front of the War on Poverty, with authority and flexibility that no Native official had ever wielded.

Wilson understood that genuine self-determination required more than rhetoric. It needed money, institutions and trained Native professionals. Under his leadership, OEO programs did something revolutionary: they sent direct federal funding to tribes, bypassing the old chokehold of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Community Action Programs, Head Start, Job Corps, VISTA — in Indian Country, these were not just social programs; they were tools to build tribal governance.

He used that moment to seed the future. Wilson helped establish graduate and professional pipelines for Native students: law programs at the University of New Mexico, Indian education and administration tracks at Minnesota, Harvard, Penn State, Arizona State and more. He pushed hard for an Indian law program that would arm tribes with their own lawyers instead of depending on non-Native intermediaries.

Dick Trudell (Dakota) spent decades, mostly in DC, working on behalf of Indian Country: “Jim was instrumental in supporting and developing programs in the education area, in particular law scholarships for Native Americans. I always enjoyed Jim’s sense of humor, and his seriousness about really making a difference for Indian Country. .Jim was a real trailblazer, in terms of his personality Jim could engage anybody about the state of Indian Affairs at that time. He was the right person at the right time, because there weren’t many Indians working in DC.”

One former student later wrote that he would never have become a lawyer without that summer law program.

Most Oglala tribal members never knew how central one of their own was to that pivot. Wilson himself rarely spoke about it. But across Indian Country, every Head Start center on tribal land, every tribal legal office staffed by Native attorneys, carries a trace of his work.

Ben Reifel

Benjamin Reifel, Wíyaka Wa.žíla — “Lone Feather” — was born in a log cabin near Parmelee in 1906. He straddled two worlds from the start: Sicangu Lakota on his mother’s side, German on his father’s, fluent in both Lakota and English. He worked his way through school, earned a degree in agriculture at South Dakota State, and went into the Bureau of Indian Affairs as a farm and field agent during the hard Dust Bowl years.

After World War II service as an Army officer, Reifel climbed the BIA ranks, eventually serving as superintendent at Fort Berthold and Pine Ridge, then as Aberdeen Area Director, overseeing programs across three states.

In 1960 he took a leap almost unimaginable for an Indian man raised under reservation rule: he ran for Congress in South Dakota’s First District — overwhelmingly white, East River farm country. He won, and for the next decade he was the lone Native voice in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Reifel fought for farm supports and water projects that shaped the Plains economy, but he also championed integrated, modern education for Native students and backed the Civil Rights Act of 1968. As a senior member of the Interior Appropriations subcommittee, he quietly steered resources toward Indian education, arts, and cultural preservation.

Today, his name survives on a visitor center in Badlands National Park, a dorm at SDSU and a Sioux Falls middle school. The first Lakota in Congress was not a celebrity activist; he was a methodical public administrator who understood that sometimes the most radical thing an Indian man could do was sit at the appropriations table and say, calmly, “No — this is what our communities need.”

We owe the next generation the full story: that real change came not just from sensational moments, but from a remarkable, unprecedented wave of Lakota and Native leadership that flowed out from places like Pine Ridge and Rosebud.

(James Giago Davies is an enrolled member of OST. Contact him at skindiesel@msn.com)

The post A forgotten generation of Lakota leadership first appeared on Native Sun News Today.

Tags: Top News