Family still searches for answers 20 years after death of Sisseton woman

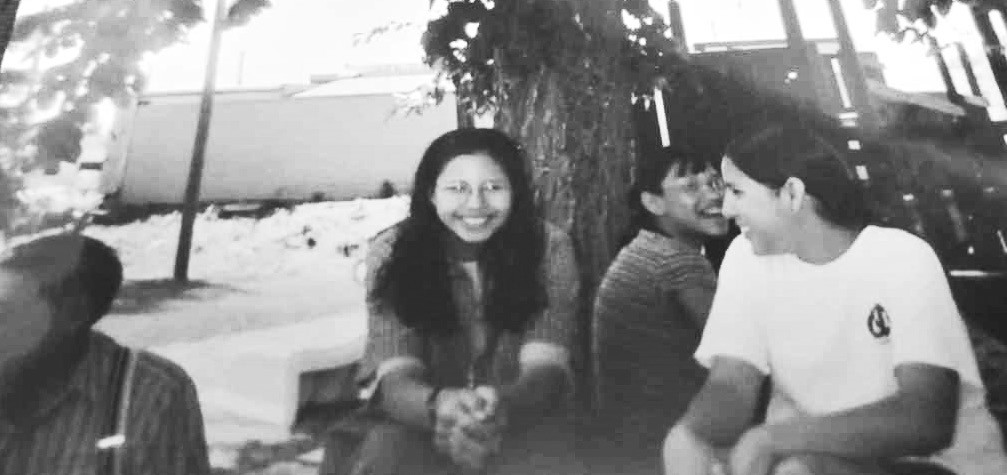

Lakota Renville was living in north Kansas City at the time of her death following a move from the Lake Traverse Reservation in northeastern South Dakota. (Courtesy Waynette Renville)

Waynette Renville remembers clearly the last time she and her three younger sisters had a conversation together.

The four Sisseton Wahpeton Dakota women, all in different cities, arranged a group phone call on the night of Oct. 15, 2005.

Cozied up in her pajamas, Waynette caught up with her siblings about their days until eventually it was just her and her youngest sister, Lakota. Not long after, Lakota abruptly got distracted and dropped off the call.

Less than 10 hours later, the 22-year-old Lakota was found dead in an empty lot in Independence, Missouri, not far from her home in northern Kansas City. She was wrapped in a blanket and discarded with a “pile of trash,” Waynette said.

Twenty years later, the Renville family still has no answers as to what happened to Lakota or how she ended up in that vacant grassy lot.

Investigators have said Lakota had recently been the victim of sex trafficking, but no suspects have been named in her death, and a DNA sample has not turned up a match.

“It’s been really hard,” Waynette said. “It’s really hard for my mom. She doesn’t like to talk about it anymore. It’s so hard for her.”

Growing up in Sisseton on the Lake Traverse Reservation, Lakota had big dreams of becoming a veterinarian and caring for animals, something she was extremely passionate about, Waynette said. A graduate of Crow Creek Tribal Schools, Lakota was also becoming interested in the internet, and a brand new social media platform called MySpace. Like many teenagers today she was captivated by social media, and her family didn’t know much about it, Waynette said.

South Dakota Searchlight and ICT have partnered on a long-term project, funded in part by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism, that aims to provide a snapshot of Missing and Murdered Indigenous People cases by combining multiple sources of data.

The publications have also created a form for people to share a tip about their missing loved one, for possible inclusion in the project.

Above, 10/16/2005. The day Lakota Renville was found deceased in the area of Pitcher Road and Blue Ridge Cutoff. (Photo courtesy of Facebook)

Sometime in 2004 Lakota told her family she met a man on MySpace. Not long after, she asked to borrow her mother’s car and drove off, Waynette said. Weeks later, Lakota called and told her family she’d moved to Kansas City to be with the man she met online.

Lakota’s life in Kansas City was, for the most part, not something she told her family much about on their phone calls. The calls were brief, and often had to be made from a payphone or someone else’s phone – only roughly half of Americans had a cellphone back then.

Through these calls, Lakota’s sisters and mother were able to piece together bits of what was happening in her life, and what they were hearing was alarming, Waynette said.

On one occasion, Lakota told her family she’d been trapped in the back of a van by some unknown men.

“(She said) they hurt her, did stuff to her, gave her drugs,” Waynette said. “She said there were some other girls there too, but they were all just staring at her.”

Lakota told her family the man she’d moved to Kansas City to be with wasn’t who he said he was either – he was abusive, controlling and much older than her, family members said.

Her family begged her to come home, sending her money to help get her back. In early 2005, months before she’d be killed, Lakota did come home for a few days, but it wasn’t long before she went back to her life in Kansas City.

On average, it can take seven attempts before a woman is finally able to be free of their abuser, but this number may be even higher among Native women, said Carole Cadue-Blackwood, who is Kickapoo and a social worker with the Kansas City Indian Center.

There’s a great lack of research and data regarding the prevalence of sex trafficking among Native women, Cadue-Blackwood said. It’s something the United States Department of Justice has acknowledged.

A May 2014 a report from the Willamette University College of Law in Oregon identified a number of issues contributing to high rates of sex trafficking among Native women, including how an overrepresentation of Native youth in the foster care system often leads to homelessness among youth who age-out and greatly increases the risk of sex trafficking.

In Kansas City, there’s little public knowledge of the Native community, Cadue-Blackwood said, let alone the missing and murdered Indigenous women crisis. She worries the general lack of awareness of Native people in Kansas City has impacted Lakota’s investigation, especially early on.

“MMIP doesn’t start when someone’s being exchanged for goods and services,” Cadue-Blackwood said. “The real piece of MMIP starts in the classroom with the absence of Native American curriculum and awareness. We are erased from people’s minds.”

Cadue-Blackwood said she feels police aren’t adequately trained on Savannah’s Act or MMIP in general. She was in graduate school when Savannah’s Act passed. It’s a bipartisan federal law signed in 2020 to improve law enforcement communication on MMIP.

The act’s passing gave her hope, hope that was quickly diminished when Kansas City police didn’t uphold their obligation to inform tribal governments and agencies of a Cherokee teen’s disappearance in 2023.

After Savannah’s Act passed, someone from the U.S. Attorney General’s Office Western District of Missouri called Cadue-Blackwood to tell her that she’d serve as the contact person if an Indigenous person were to go missing in western Missouri, per the act’s guidelines.

“I have yet to be contacted by the attorney general’s office about any Native American being missing in my four-plus years of being here at the Indian center,” Cadue-Blackwood said.

Oftentimes because of historic barriers to housing, food insecurity, generational trauma and difficulty accessing jobs, Native women and girls can be easy targets for a sex trafficker, Cadue-Blackwood said.

Missouri has the fourth highest rate in the nation for sex trafficking, according to a report from the Missouri House Statewide Council on Sex Trafficking. A lot of this has to do with the geological placement of the state and the connection of major highways through Kansas City.

As investigators picked at Lakota’s life in Kansas City, they informed her family that she’d been sex trafficked while living there. Waynette said police told her the man Lakota thought was her partner was really a sex trafficker who had cut her off from family, isolated her in a new city and controlled her life.

Renville isn’t an anomaly. Roughly 40 percent of sex trafficking victims are trafficked by an intimate partner.

Sex traffickers work carefully to gain the victim’s trust, create dependence and promote the idea that selling sexual services is normal and necessary, according to the Polaris Project, the nonprofit organization behind the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline. By moving her to Kansas City, Lakota had been isolated from her support system, family and community in an unfamiliar area.

In the early days of the investigation, police also believed her killer may have picked her up at Independence Avenue and Myrtle Avenue, an area that’s always had a reputation for trafficking, whether it’s drugs or people, the Kansas City Star newspaper reported in 2012.

Witnesses at the scene reported seeing a brown, 1990s model Ford Explorer parked where Lakota’s body was found shortly before she was discovered.

Authorities believe that Lakota was killed somewhere else and then transported to the vacant lot off Pitcher Road and Highway 40. She was wrapped in a unique wool western blanket, blue-ish gray with a large steer skull.

Investigators did gather a rape kit from Lakota, which has been entered in the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, also known as CODIS, but so far hasn’t identified a match.

Police say Lakota had been lured into becoming a sex worker, and that her last noted interaction was with a client around 3:30 a.m. That man was later identified and cleared, and so was Lakota’s boyfriend.

Early reporting in 2005 referred to Lakota as a prostitute and not much else – which Cadue-Blackwood described as an aspect of victim blaming that could have impacted early investigation efforts.

‘Justice for Lakota’

Waynette serves as the point person for the family discussing her sister’s case with police, news outlets and others. Her mother, Julie, is an elder now and talking about her youngest child’s death is too hard for her, Waynette said. Waynette herself has gone through a lot in the decades since her sister’s murder. She’s survived a stroke which limited her ability to travel and is adjusting to life with a lupus diagnosis and connective tissue disease.

But Waynette is still and has always been passionate about solving her sister’s death.

In 2007 she heard a tip that someone at a biker bar outside of Kansas City might know something about Lakota’s death. So she drove 500 miles from Sisseton to Kansas City to find out for herself, frustrated by a lack of police communication.

The parking lot was filled with bikers, none of whom seemed to ever have seen a Native woman before, Waynette said.

“There’s all these White bikers staring at me,” Waynette said. “It was scary.”

Despite her fear, Waynette went into the bar. While nothing came of it, that didn’t discourage Waynette from continuing to push for justice.

In 2025, there are still no named suspects in Lakota’s death.

Independence Missouri Police said the case is still active and in early 2025 the Kansas City suburb pledged $100,000 towards solving Kansas City cold cases including Lakota’s.

The Independence Police Department planned a social media push to bring attention back to Lakota’s death in October on the 20th anniversary of her death, said Bryan Conley, community engagement officer with the Independence Police Department. Investigators are hoping to bring the case back to the public’s attention and hopefully gather more information and tips.

But Waynette said the family has received little support or communication from the Independence Police Department in the 20 years since Lakota’s death, which led her to take a different approach – social media. Waynette said she works through social media to help spread Lakota’s memory and information about other missing people.

About 10 years ago Waynette discovered a Facebook page that someone else had created called “Justice for Lakota Renville.” The creator transferred the page and its information to Waynette, who has since garnered more than 160 followers.

Every year on the anniversary of Lakota’s death, the Kansas City Indian Center holds a candle light vigil at the lot in Independence where Lakota was found.

Gaylene Crouser, executive director of the Kansas City Indian Center, said she remembers seeing Lakota on the news 20 years ago following her murder.

“It was heartbreaking,” Crouser, Standing Rock Lakota, said. “Somebody knows something. And maybe the further in time it gets, they’re less likely to want to protect someone or cover that up. As time moves on maybe they’ll be willing to step forward and say what they know.”

Anyone with information on Lakota Renville’s death is encouraged to call the Independence Police Department or the TIPS Hotline at (816) 474-TIPS.

(Amelia Schafer is the Indigenous Affairs reporter for ICT and is based in Rapid City. She is of Wampanoag and Montauk-Brothertown Indian Nation descent.)

The post Family still searches for answers 20 years after death of Sisseton woman first appeared on Native Sun News Today.

Tags: More News