Telling Natives to go back to where they came from

Terray Sylvester / Reuters Dakota Access Pipeline protesters square off against police near the Standing Rock Reservation and the pipeline route outside the little town of Saint Anthony, North Dakota on Oct. 5, 2016.

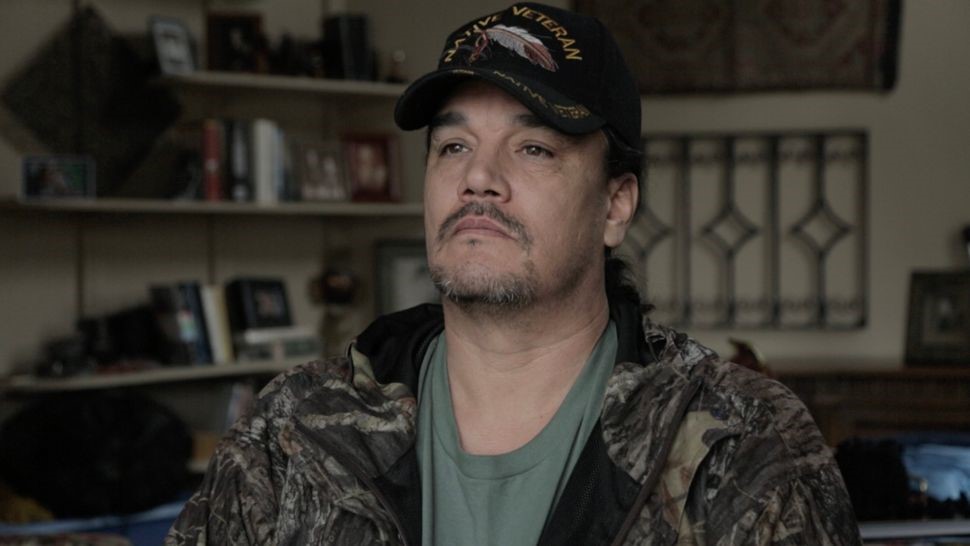

Jonathan Klett, Liminal Films Rattler, legal name Michael Markus, is a 46-year-old Marine veteran who is the descendant of Chief Red Cloud, the Lakota leader who signed the 1868 Ft. Laramie Treaty.

Lori Metoxen, 52, works as an administrator at Oneida Behavioral Health in Green Bay, Wisconsin, a treatment center for indigenous people suffering from addiction and mental illness. Metoxen says one beautiful summer day in 2017 she drove home from work with the windows down, the sunroof open, and her Oneida Nation license plate, available only to members of the tribe, proudly displayed on the back of her car. When she stopped at a traffic light in the part of western Green Bay that belongs to the Oneida Nation reservation, she noticed a car full of white, teenage girls in the lane beside hers.

“Go back to Mexico, you scumbag sack of shit!” one of the girls yelled at Metoxen.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Stunned, Metoxen remembers saying something like, “What is your problem?” to which the girl, after a string of profanities, replied, “You heard me, go back to Mexico!”

“The angriness of their voices was shocking to me,” Metoxen, a Native American who is not from Mexico, recounted to HuffPost. “They really needed to make somebody feel bad. What was the fun in that?”

After a few seconds, the light turned green and the white girls, all laughing, turned left. Metoxen drove straight, and as so often happens after incidents like these, she suddenly realized what she should have said.

“You go back to where you came from! I belong here!”

A White Supremacist Slur

Metoxen’s story is one of 22 stories HuffPost has collected of people with Native American ancestry being told — absurdly — to “go back” to where they came from.

Native Americans reported being told different variations of the phrase: “Go back to your country,” “go back to Mexico,” “go home,” “get out of our country,” and “go back to the reservation.”

For a white person — and it’s almost always a white person — to say “go back” to a Native American, whose ancestors were here long before European settlers colonized this continent, betrays the real, white supremacist meaning of the phrase: We don’t want you anywhere at all.

These 22 stories were culled from over 800 reports of hate incidents, occurring over the last four years in the U.S., in which assailants communicated some variation of “go back” to their victims. HuffPost, working with ProPublica’s Documenting Hate project, collected these incidents in a database to examine the moral emergency of hate in the era of President Donald Trump.

The 22 incidents occurred in 15 states, from a post office in Alaska to a Walmart in Arizona, from a library in Washington to that traffic intersection in Wisconsin.

Five of the perpetrators in these hate incidents invoked the president’s name while targeting their victim; six yelled “go back” from cars before driving off; six yelled “go back to Mexico” at their victims, none of whom are from Mexico; and of the perpetrators whose race is known, all were white.

Of those Native Americans who were told to “go back” where they came from, three were veterans of the U.S. military.

Some of those interviewed by HuffPost for this article expressed fears that anti-indigenous bigotry is on the rise thanks to the election of President Trump in 2016 — a man with a long history of racism towards Native Americans.

Trump, after all, keeps a portrait of Andrew Jackson in the Oval Office, the 19th century president best known for his policy of “Indian Removal,” an ethnic cleansing campaign that included the Trail of Tears, the forced death march of Native Americans from their homes in the Deep South to points west, like Oklahoma, where 57-year-old Jennie Wright lives.

“I look Indian,” Wright, a high school English teacher, told HuffPost. Her father was white but her mother, she said, was an enrolled member of the Mississippi Choctaw tribe.

A couple weeks after the 2016 election, Wright says she went to a Walmart in Bartlesville, a short drive from the Osage Reservation (where Native Americans in the early 20th century, newly wealthy from oil discovered on that land, were systematically robbed and murdered.)

As Wright crossed a crosswalk in the Walmart parking lot, she suddenly heard the sound of a revving engine. She looked around and saw a middle-aged white woman in a “beat-up old car” speeding towards her. Wright scurried towards the sidewalk.

The woman in the car stopped, leaned her head out of the window and yelled at Wright to “go back” to where she came from. “What the hell are you talking about?” Wright replied.

“Go back to Mexico!” the woman screamed, before speeding off and yelling, “Trump!”

Wright says it was the first time anything like this has ever happened to her. “It opened my eyes a little bit,” she told HuffPost. “I always thought everything was pretty much okay. Thought it died out.”

“Then he came,” she added, referring to the president. “And he gave everyone free rein to say things.”

A survey conducted in 2017 by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Harvard University found that nearly 40% of Native Americans said they had personally experienced offensive comments about their race or ethnicity. Over a third of those surveyed said they or a family member had experienced either violence, threats or harassment because they are Native American.

Cheryl Redhorse Bennett, an assistant professor at Arizona State University who studies hate crimes targeting indigenous people, says she’s seen a “surge” in Native Americans being told to “go back” since 2015.

Although she’s seen her fair share of Native Americans being the victims of anti-Hispanic hate (being told to “go back to Mexico”), she says perpetrators most often tell Native Americans to “go back to the reservation.”

“Generally native people refer to towns that are adjacent to reservations as border towns,” Bennet explained to HuffPost. “Within these border towns, there’s a long history of violence against native people, racism, and hate crimes.”

Bennett said white border town residents often view reservations and treaty rights not for what they are — meager compensations for centuries of theft and genocide — but as “privileges” unfairly bestowed upon Native Americans.

“You tell native people to ‘go home,’” Bennett said, “but then you want to develop their land, you want to abolish treaty rights. So it’s never enough.”

“We Were Here First!”

Rattler, legal name Michael Markus, is a 46-year-old Marine veteran who is the descendant of Chief Red Cloud, the Lakota leader who signed the 1868 Ft. Laramie Treaty.

Rattler was among thousands of Native activists in 2016 who set up camp on land that treaty protected: the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota. This was Rattler’s ancestral land, and he was going to protect its ancient burial sites and its water from the planned construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. The pipeline, he and other activists argued, was a violation of that treaty.

It was also a violation of that treaty, they later claimed, for state law enforcement officials to invade the native activists’ unarmed encampment on Oct. 27, 2016, using sound cannons, rubber bullets, pepper spray, and tanks to disperse the protesters. Rattler was among a handful of activists who allegedly set barricades of tires and wood on fire to slow the violent police raid.

For this, months later in February, just after Trump’s inauguration, he was indicted on federal charges of civil disorder and of using a fire to commit a felony. He and other activists saw the indictment as political — an excuse to justify the police brutality visited upon the encampments.

As he awaited trial, Ratter’s bail conditions stipulated he had to wear an ankle monitor and not leave the area in and around Bismarck, North Dakota — a border town.

It was during this period, he told journalist Natasha Lennard, author of the book “Being Numerous: Essays on Non-Fascist Life,” that local residents would often drive past Rattler and yell “go home!” as he smoked cigarettes on his porch.

Jonathan Klett, Liminal Films Rattler, legal name Michael Markus, is a 46-year-old Marine veteran who is the descendant of Chief Red Cloud, the Lakota leader who signed the 1868 Ft. Laramie Treaty.

It’s a striking scene to imagine: a Native American Marine veteran wearing an ankle monitor, awaiting trial for protecting tribal land from the fossil fuel industry, being told to “go home” by white people driving by.

“It’s funny, because I want to get out of here too,” Rattler told Lennard at the time. “But part of me wants to yell back, ‘Go home? We were here first!’”

As Rattler awaited trial, President Trump approved the final permit for the Dakota Access Pipeline, which over the next year spilled oil five times, just as native activists had warned it would.

Rattler, after accepting a non-cooperating plea deal, is now serving a three-year sentence in a federal prison in South Dakota.

In a statement released to the press after his sentencing, he said he was praying that native activists had “the strength to keep up the fight.” Standing Rock, he said, “was a training ground.”

And despite what he and other activists thought about the federal government’s motivations for prosecuting him, Rattler also stated he was praying for the judge who handled his case.

“We all live on this earth together,” he said. “They segregate us because we have a different color skin, but we’re all red underneath.”

(Article courtesy of the Huffington Post)