Frozen Ice Age bison reopens extinction debate

Buried in ice for 30,000 years, the steppe bison recently pulled out of the Yukon permafrost gives the relatives of today a graphic window into the world of our paleo Indian ancestors. Science verifies many of the stories passed down by our ancestors, but it also often characterizes their behaviors in an uncharitable light.

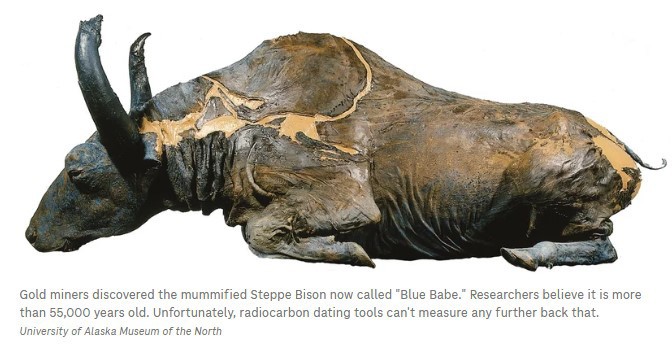

The steppe bison is one of the best-preserved ice age mammals ever found. It still has fur. Organs. Eyelashes. Even the contents of its last meal. That’s not a fossil. That’s a time traveler. And it’s telling a story older than science itself, in a way fossilized bones alone never could.

For reasons not yet scientifically determined, the megafauna of the Ice Age (the large animals) all went extinct, the last species dying off in some cases less than 10,000 years ago. Controversy reigns about who killed off the mammoths, the short-faced bears, the saber-toothed cats. The Overkill Hypothesis seems to hold special attention for science, although measures have been taken to incorporate tribal perspectives. The Overkill Hypothesis asserts: the extinction of this megafauna was greatly if not wholly triggered by the hunting habits of our ancestors, as in, we killed them all off. We, the over-hunters. The primal culprits.

It is never explained why the peoples of Africa and Asia never hunted their megafauna, particularly elephants, to extinction, but apparently a few million paleo Indians, over the course of ten thousand years, not even having invented the bow and arrow yet, did.

What is often not incorporated into the scientific perspective is what most tribal nations understand; the interdependent relationship between people and the animals we ate to survive. Our ancestors had a great respect and understanding for the bison, and they did not take his life wantonly. It is not a stretch of logic to assert they would have interacted with the mammoth similarly.

“We’ve been here for thousands of years,” said Trina Billy, a citizen of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation and cultural educator in Dawson City. “If our people wiped out the mammoths, how come the bison made it through? How come the caribou are still here? We didn’t destroy—we adapted.”

There have been many mass extinctions in this planet’s history, the last one being these Ice Age megafauna. Ninety nine percent of all species to have lived are extinct. What you see all across this planet, down to the microorganisms you can’t see, represent just one percent of all living things to have occupied this earth. And there were no paleo Indians around to trigger the extinction of the ninety-nine percent. When the Ice Age ended, their tundra buffet turned into a soggy boreal stew. That steppe bison died in a mudslide during thaw season. The earth changed faster than he could pivot. Just like it’s doing now.

Many scientists believe that a culture that drove the passenger pigeon extinct in a single human lifetime—with rifles, railroads, and industrial-scale indifference, had the same destructive impact on megafauna as small and scattered bands of Clovis hunters.

The frozen steppe bison was Bison priscus—ancestor of today’s American bison. It had twenty percent more muscle mass in its neck and shoulders, probably to push through snowdrifts and outcompete rut rivals. It stood six feet at the shoulder and weighed as much as a Toyota Tundra. And yet it still ended up buried in muck. No arrows. No slash wounds. No butcher marks. Just gravity and spring melt.

Balance of nature is something tribes maintained not out of principle or concern about the environment, but because if the balance was broken, tribes paid for it with famine and grief.

Tribes cannot compete with the perspective of science, but science cannot research and theorize and replicate tribal perspective and history. Nothing rivals the power and truth of science, and science will inevitably develop a comprehensive understanding of what killed off the Ice Age fauna, but at present, they should stop crediting or scapegoating tribes as a shortcut solution to solving that puzzle.

Back in 1984, a paleontologist named Dale Guthrie cut a chunk of meat off “Blue Babe,” a bison found frozen near Fairbanks, Alaska. He made a neck stew out of it. Ate it. Said it tasted “like what I would have expected, with a little bit of wring of mud.”

Guthrie’s act was actually a step in the right direction; he recreated the relationship a tribe would have had with such an animal and personalized his interaction with the bison down to a taste of its meat, without sacrificing his informed, scientific perspective. He balanced the two, and this hands on retrograde immersion into how the paleo hunter would have interacted with this bison, can allow science to factor human participation through the perspective of the tribe living in that time. When Columbus came ashore on the white sand beaches of San Salvador in 1492, the tens of millions of Indians across two continents were not hunting critically important megafauna into extinction.

Tribal over-hunting as a major contributive factor is also mentioned for the direct extinction of the giant ground sloth, and indirect factor in the extinction of the saber tooth cat, since he was denied his food source. In the Black Hills there are no wolves, no bears, but when Jedidiah Smith first came to the Black Hills in 1822, there were so many bears he was mauled by one right at the edge of the Hills. The prairies teemed with bison, despite the tribes acquiring the horse and vastly improving their capacity to hunt them. None of these animals disappeared from the landscape until White hunters and settlers arrived. Then they were wiped out, in about a century. It is rationalized that tribes did not have the numbers to impact the wolf, the bear, the bison, to the edge of extinction, but these same scientists assert that the paleo Indian could accomplish this with smaller numbers and vastly inferior weapons and larger, tougher prey to hunt. Scientists almost unanimously assert climate change is a threat now, but climate change over the course of tens of thousands of years, couldn’t have killed off the cold-adapted Ice Age megafauna, after the mile high walls of ice were all melted?

(James Giago Davies is an enrolled member of OST. Contact him at skindiesel@msn.com)

The post Frozen Ice Age bison reopens extinction debate first appeared on Native Sun News Today.

Tags: More News