Hand counting vs. voting machines: Debate rages in South Dakota

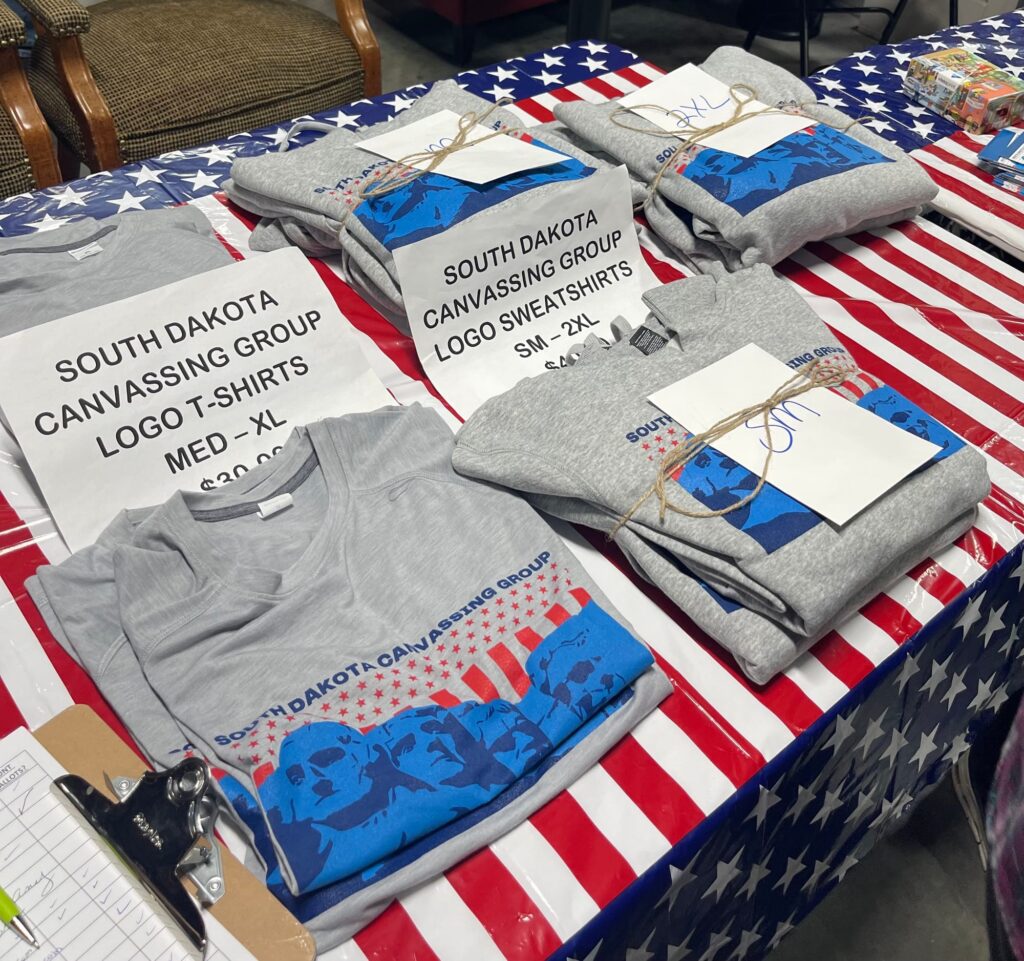

T-shirts for sale at a South Dakota Canvassing event at the Military Heritage Alliance in Sioux Falls, S.D., on Oct. 19, 2023. The group was formed after My Pillow founder Mike Lindell held his cyber symposium in Sioux Falls in August 2021. (Photo: Stu Whitney / South Dakota News Watch)

Most of the county officials who administer elections in South Dakota don’t consider hand counting to be an effective or efficient method of tabulating votes.

That’s the result of a South Dakota News Watch survey that saw input from 49 of the state’s 66 county auditors. Auditors are elected officials who supervise county, state and federal elections as well as maintain financial records and other duties.

Nearly 90% of those who responded (43 of 49) answered “no” to the question of whether hand counting is an “effective and efficient method of tabulating ballots.” One auditor responded “yes” and four were uncommitted. There was one “no comment.”

“(Counting votes by hand) increases the chances of human error and is extremely time-consuming,” said Douglas County Auditor Phyllis Barker, echoing the concerns of many of her peers. “I have complete trust in the tabulation machines we currently use.”

Many of the auditors noted that South Dakota passed a law in 2023 requiring post-election audits using hand counts of randomly selected precincts to make sure results match up with machine tabulations. There are also test decks used to evaluate the accuracy of electronic vote counters before each election.

Machine vote tabulators must have an error rate no worse than 1 in 500,000 to be certified by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. A Nevada election official in Nye County, with more than 10,000 voters, recruited hundreds of volunteers to hand-count ballots in November 2022 after expressing skepticism about machines. He estimated a human error rate of 25% after the first day.

“Hand counting has its place,” said Spink County Auditor Theresa Hodges. “For small municipal and school elections, with generally one to two contests on their ballots, it is doable and the most responsible decision fiscally for those entities. For larger elections with multiple contests, hand counting leaves too much room for human error and is not the most efficient way to tabulate results.”

Minnehaha County auditor voices support

The most steadfast support of hand counts came from the state’s most populous county: Minnehaha County Auditor Leah Anderson. She has clashed with county commissioners by expressing distrust of election technology and advocating hand counting, a position held by South Dakota Canvassing Group, a grassroots organization pushing for election reform.

“If done properly with a good system in place and training ahead of time, (hand counting) can definitely be effective and efficient, especially in smaller counties,” Anderson told News Watch. “In Minnehaha County, we would need a larger volume of volunteers with equal party representation to make it happen effectively and efficiently.”

Anderson said she is not formally involved with South Dakota Canvassing, the citizen group behind a campaign to lobby counties to adopt hand counting for 2024 or bypass county commissions by forcing a public vote through petitions.

She has engaged in hand counting demonstrations and research with computer analyst Rick Weible, a “friend and ally” of South Dakota Canvassing who has been instrumental in urging South Dakota legislators for stronger election security.

“(South Dakota Canvassing) does not have membership and I am not formally involved other than consideration of research they provide,” said Anderson, who ousted incumbent Republican Ben Kyte in the 2022 primary. “I am friends with some of the founders and I appreciate all of the work they do in researching topics.”

Fall River, Gregory will hand count for 2024 elections

The hand count debate comes as South Dakota is viewed as a proving ground by election reformists who claim that recent elections across the county were marred by hacking or fraud, allegations repeatedly rejected by courts of law as well as Democratic and Republican election leaders.

One of the most prominent voices is My Pillow founder and Donald Trump supporter Mike Lindell, whose 2021 “cyber symposium” in Sioux Falls inspired South Dakota Canvassing founders Jessica Pollema and Cindy Meyer to scrutinize what they see as voting system vulnerabilities.

The group first drew attention in 2022 by filing lawsuits and freedom-of-information requests seeking to acquire cast vote records from the 2020 presidential election, in which Democratic candidate Joe Biden defeated Trump, a Republican.

Lindell had Pollema as a guest on his web show in late February and praised the use of citizen petitions and public pressure at county commission meetings to try to restore the use of hand counting for the 2024 election cycle.

County commissions in Fall River and Gregory counties already have voted to use hand counting in 2024 after hearing public comment. Petitions with the required number of signatures have been submitted in Lawrence and McPherson counties, which will likely trigger public votes on the issue.

Rick Weible and Jessica Pollema give a presentation to Concerned Citizens of Lincoln County at an October 2023 event in Sioux Falls, S.D. “If you want to get rid of election deniers, you have to let them be part of the process,” Weible said. (Photo: Stu Whitney / South Dakota News Watch)

‘Purveyors of false claims’ spread doubts, official says

The South Dakota Canvassing website lists more than a dozen counties in which requests for petitions or signature collection have occurred. Pollema, who ran unsuccessfully for Lincoln County auditor in 2022, didn’t respond to a request from News Watch to clarify how many counties are seeing active signature collection.

“This is the chance we have to blaze the trail for our whole country to get rid of these machines,” Lindell said during the Feb. 22 web show. “This is the plan I had (a while ago), and South Dakota is just out in front of everybody. They have the perfect prototype.”

South Dakota Secretary of State Monae Johnson, who made statements during her 2022 campaign that connected her to election denialism, has been critical of some of the South Dakota Canvassing’s activities as well as Weible’s efforts to impact state election law.

In a statement to News Watch from Johnson’s office, state elections director Rachel Soulek expressed confidence in the optical scan paper ballots with high-speed counters used statewide in South Dakota for nearly two decades.

“Many voters are unfamiliar with how elections are run in South Dakota, and in recent years, purveyors of false claims have taken advantage of that lack of knowledge to spread doubts about certain aspects of the voting process,” Soulek said.

“Secretary Johnson and the South Dakota Election Team are confident in tabulation machines used in South Dakota, the safeguards built in throughout the process and the post-election audit on the machines after the primary and general election to ensure they are working properly.”

‘Are their concerns overblown?’

South Dakota Canvassing has provided a template for county initiative petitions calling for elections to be conducted by paper ballots only, with no electronic voting devices or tabulators. Residents need to gather signatures from 5% of registered voters in the county, based on the total number of registered voters (active and inactive) in the last general election.

Advocacy at county commission meetings is also strongly encouraged by the group, as evidenced by Matthew Monfore’s successful push to get Fall River county commissioners to approve hand counting for the 2024 primary election on June 4.

Monfore, an evangelist and election skeptic from the West River town of Oral, is associated with South Dakota Canvassing. He’s running for a state House seat in District 30.

“Some of these people are doing everything they can to try to make sure that every ballot is counted,” said Fall River State’s Attorney Lance Russell, a former state legislator who also served as executive director of the South Dakota Republican Party. “From that standpoint, I don’t feel that it was inappropriate to have the discussion. Are some of their concerns overblown? I believe they probably are. But maybe making sure that the public has confidence in our elections outweighs that.”

In south-central South Dakota, where former Democratic legislator Julie Bartling serves as Gregory County’s election official, the county commission voted March 6 to switch to hand counting for the 2024 primary and general elections after hearing concerns about election security from residents.

“I am disappointed that (the commission) would not give the procedure of the post-election audit an opportunity to squelch any concerns of the individuals who pushed for the hand count,” Bartling told News Watch.

South Dakota mandated machine counting in 2005

South Dakota purchased Election Systems & Software voting systems in the aftermath of the contentious presidential election of 2000, when a U.S. Supreme Court ruling regarding vote recounts in Florida elevated Republican George Bush over Democrat Al Gore.

Confusion surrounding Florida’s punch-card ballots led Congress to pass the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) in 2002. The law established standards for federal elections through the Election Assistance Commission, paving the way for South Dakota to adopt automatic tabulating and electronic ballot marking as state law in 2005.

Chris Nelson, a Republican who was secretary of state from 2003 to 2011, worked with county auditors to choose optical scan ballots with high-speed counters as the standard for South Dakota.

“One of the key reasons we went to that is because we have a paper backup,” said Nelson, who currently serves on the Public Utilities Commission.

“We’re going to use the high-speed counters so we can get a quick, accurate count on election night. But that’s the unofficial result. We know that if there’s a question about the legitimacy of that, we’ve got the paper ballots, and we can go back through a recount or audit procedure. There’s no need for cast vote records. We can go back through the paper and see exactly how each person voted.”

Tired election workers not as accurate as machines

Before 2005, South Dakota counties were using four different types of balloting systems – punch cards, hand counting, optical scan ballots that were hand-fed into a counter and optical scan ballots with high-speed counters.

“I lived through hand counting,” Nelson told News Watch. “You had election workers who would be at the polling place at 6 in the morning, they would work until the polls closed at 7 at night, and then they would begin counting ballots by hand. And if you’ve got a general election ballot with maybe a dozen different candidate races and half a dozen ballot questions, you’ve got hundreds and hundreds of ballots, maybe even thousands of ballots, in your precinct. You’ve got these folks working until 2 or 3 in the morning, trying desperately to accurately count ballots, and the accuracy just falls away. It’s not there.”

Asked about bringing in a different crew to count ballots, Nelson said that “the difficulty lies in simply finding that many people, especially since you’ve literally doubled the number of people that you need to operate your polls.”

Poll workers are typically paid. In Minnehaha County, for example, precinct superintendents make $250 a day and precinct deputies make $200 a day. The advent of automated counting machines allowed precincts to become consolidated, with the statewide number reduced to 687 for the 2022 general election.

“Back when I started there were probably three times that many (precincts),” Nelson said. “With the machines, you could reduce the number of precincts and make it a whole lot more efficient and cheaper because you have less people working. And if we were to go back to hand counting, with some of these precincts you’re talking thousands and thousands of ballots. You would have to make your precincts smaller to handle the number of ballots with humans doing the counting.”

Hand count demo held in Pierre

Making precincts smaller and adding poll workers is part of the plan advocated by Weible, a small business owner and former small-town mayor from Minnesota who now lives in the eastern South Dakota town of Elkton.

Weible supervised a hand counting demonstration at the South Dakota Capitol on Feb. 23, using a method that he and Minnehaha County’s Anderson promote as an effective way to replace machine tabulations.

It involves teams of four, with two people looking at the ballot and calling the race and two people tallying the results. The theory is that it can count 250 ballots of one race in under 10 minutes.

“So for a county that has 2,500 or fewer ballots, it would take about 1.5 hours per race or ballot question with four people on the counting board. With more counting boards of four people, that estimate would decrease,” Anderson said.

News Watch asked Weible about his past appeals for post-election audits, which South Dakota legislators adopted in 2023. The new law requires 5% of randomly selected precincts in a county to manually count votes in two contests.

“Here’s the problem: We’re doing less than half a percent of ovals (filled-in votes) in the election,” Weible said. “Would the IRS accept an audit of your bank accounts if you only gave them the December statement?”

Nelson counters that South Dakota has had “dozens and dozens” of recounts since machine tabulators were adopted in 2005, with no major discrepancies found.

“They might move one or two votes this way or that way, based on how an oval was filled in or not filled in,” Nelson said. “But in those 20 years, nobody in any of those recounts uncovered any kind of fraud or error in a counting machine. So any suggestion that we ought to go back and do it some other way that is proven to be less accurate just doesn’t make sense to me.”

Bill to rein in petitions falls short in legislature

The petition drive for hand counting encountered friction in Pierre when concerns were raised about federal election laws being violated, likely leading to county governments being sued.

The original petitions that circulated stated that “electronic voting machines and electronic tabulation devices of any kind” would be prohibited.

Such action would violate the Help America Vote Act, according to Rapid City attorney and election law expert Sara Frankenstein. She sent a message to lawmakers noting that states are obligated in federal elections to provide “at least one direct recording electronic voting system or other voting system equipped for individuals with disabilities at each polling place.”

To comply with HAVA, South Dakota uses ExpressVote machines to help the visually impaired, those who cannot hold a pen and those with other disabilities mark a paper ballot.

Legislators amended a vehicle bill (House Bill 1140) to allow county commissions to keep a petition from reaching public vote if it violates state or federal law, adding an emergency clause to allow it to take effect immediately. The House rejected that amendment, prompting new language that removed the emergency clause and allowed petition sponsors to withdraw the petition prior to the election being scheduled. That amendment also failed, killing the bill and its amendments.

“So we’re stuck with ordinance language our legal counsel states is in direct violation of state and federal law,” said McPherson County Auditor Lindley Howard, also a member of the State Board of Elections. “If the voters vote for this ordinance we will have lawsuits. If we illegally deny the petition, then the petitioners will file a lawsuit. I feel like counties were left swimming in an ocean without a lifejacket.”

Prior to the House vote, Pollema disputed Frankenstein’s legal conclusions in an email addressed to “every elected official in the state of South Dakota,” asserting that federal election laws contain separate provisions for states with paper ballot voting systems.

“Federal and state laws clearly have protections for machine-free voting and counting,” Pollema wrote in the email, which was obtained by News Watch. “Any lawyer who is promoting an opinion to the opposite is unethically and immorally weaponizing the law to fit a politically motivated agenda, and is in clear violation of the code of conduct for lawyers per State Bar Association rules.”

Despite this stance, South Dakota Canvassing changed the wording on its sample petitions to say that electronic voting machines are prohibited “with the exception of devices for those with disabilities.” The original wording still stands on the petitions submitted to McPherson and Lawrence counties.

‘Guess it didn’t fit their narrative’

Jim Eschenbaum, a semi-retired farmer from Miller who serves as a Hand County commissioner, thinks some of the election reformists have gone too far.

At first, he attended South Dakota Canvassing meetings to hear more about claims that the 2020 and 2022 elections were susceptible to hacking or fraud.

He heard concerns from fellow residents in his central South Dakota county, where voters gave Trump 62% of the vote in 2016 and 2020 and favored a Democratic candidate for president just once in the past 90 years – Lyndon Johnson over ultra-conservative Barry Goldwater in 1964.

“I told the South Dakota Canvassing Group on a regular basis, ‘Thank you for what you are doing. You have definitely awakened the people of South Dakota,’” Eschenbaum said.

Along with Hand County Auditor Doug DeBoer, Eschenbaum received permission from the secretary of state’s office to pull the ballots from the 2020 election and perform a hand-counted audit to test out the county’s machine tabulators. The process was videotaped and later posted to YouTube.

“We had two election judges from the county, one Republican and one Democrat, and we randomly chose two precincts from the 2020 general election,” Eschenbaum told News Watch. “We found that all the ballots that went through the tabulators were counted 100% correctly.”

Four mail-in ballots had not gone through the machines in one precinct, which they traced to human error. When they did another audit for the 2022 primary election, the machine count came out accurate once more.

Eschenbaum and DeBoer said they reported their audit to South Dakota Canvassing but that the group did not include the findings as part of its online reports or presentations at community gatherings across the state.

“Transparency appears to be a one-way mirror,” said DeBoer, who also served as Hand County sheriff for 17 years. “I guess it didn’t fit their narrative.”

For Eschenbaum, the experience showed that the current wave of electoral activism in South Dakota is more about tearing down the system than finding common ground in an effort to maintain election integrity.

“The state passed a law to mandate post-election audits after South Dakota Canvassing pushed for that,” Eschenbaum said. “That’s what they wanted, and when they got that, now they want to get rid of all the machines. I cannot speak for any other tabulators. I cannot speak for any other county. I will just assure people in Hand County that we’ve done our due diligence in making sure that the election count was correct. That’s what we wanted to know.”

The post Hand counting vs. voting machines: Debate rages in South Dakota first appeared on Native Sun News Today.