Hate speech

NCAI President Mark Macarro responds to conservative commentator Ann Coulter who this past weekend sent shockwaves through Indian Country and beyond when she posted on X “We didn’t kill enough Indians.”

RAPID CITY—A single sentence—six words—posted on social media by conservative commentator Ann Coulter this past weekend sent shockwaves through Indian Country and beyond: “We didn’t kill enough Indians.”

The tweet, in response to a clip of Diné professor and activist Melanie Yazzie speaking at the Socialism 2025 conference, quickly went viral on X (formerly Twitter), prompting widespread outrage from tribal leaders, Native organizations, elected officials, and ordinary citizens.

For many, the post echoed not just ignorance, but centuries of institutional violence against Indigenous peoples—violence that includes massacres, cultural erasure, forced removals, and systemic neglect. Yet, despite its genocidal overtones, Coulter’s post remains protected under the U.S. Constitution.

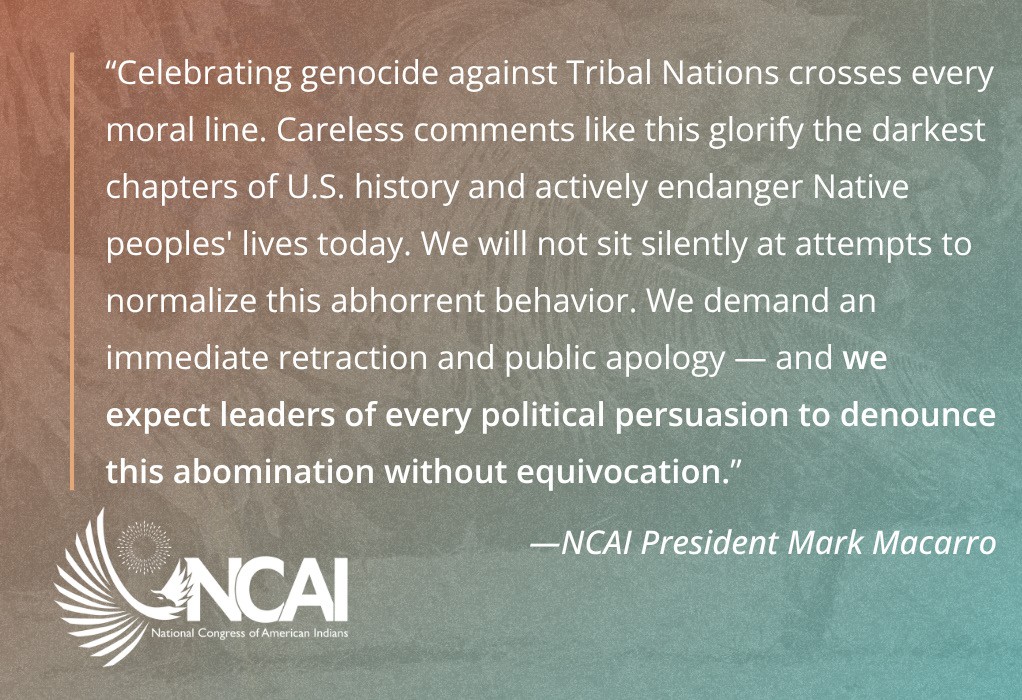

“Celebrating genocide against tribal nations crosses every moral line,” said Mark Macarro, president of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI). “Careless comments like this glorify the darkest chapters of U.S. history and actively endanger Native peoples’ lives today. We will not sit silently at attempts to normalize this abhorrent behavior.”

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. called the tweet “beyond abhorrent” and said it should be repudiated by leaders of all political affiliations. “This is not just offensive. This is language that echoes genocide and implicitly encourages it,” he said. “The country frequently seems on the verge of political violence. Coulter’s post implicitly encourages it.”

John EchoHawk, executive director of the Native American Rights Fund, described the tweet as “ignorant, immoral, and unacceptable,” noting that such statements help normalize dehumanization. “This is a moment for all Americans to say: enough.”

For Cherokee journalist and advocate Rebecca Nagle, Coulter’s tweet is just another chapter in a long, ugly narrative. “It’s all just to get likes, to rev up her base at the expense of Indigenous lives and dignity,” Nagle said. “She’s celebrating what our people endured and survived. That’s why it cuts so deep.”

Tasha Mousseau, vice president of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, echoed that sentiment. “In Indian Country, we are still here, thriving, and we are our ancestors’ wildest dreams,” she said. “But remarks like this are a reminder of the violence our people have survived— and still face.”

The Sooner State Party, a new political movement in Oklahoma, issued a statement denouncing Coulter’s post as “Third Reich beliefs” and “abhorrent bigotry.” They called for a complete boycott of Coulter’s media and book appearances, saying, “In Oklahoma, we rise against the repugnant mindset of hatred displayed by Coulter.”

The pain is amplified by history. Coulter’s words conjure up a long line of American presidents who expressed hostility toward Native people.

From George Washington comparing Native Americans to “beasts of prey,” to Thomas Jefferson’s call for extermination or removal, to Andrew Jackson’s open disdain, and Theodore Roosevelt’s infamous declaration that “I don’t go so far as to think the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every 10 are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the 10th.”

The words of past presidents often moved beyond rhetoric and into law, laying the foundation for policies of genocide, relocation, and cultural destruction. For many Native people, Coulter’s tweet felt less like an outlier and more like a continuation.

Though X initially placed a content warning on Coulter’s post, it remained visible for over 24 hours. As of this writing, she has not apologized or retracted her words. Her post has been shared more than a million times.

NCAI and other Native organizations have called on X to remove the post entirely and ban Coulter from the platform. So far, there has been no response from X’s owner, Elon Musk, but it is very likely Musk will not take down such an offensive remark as he has previously stated, “If we lose freedom of speech, it’s never coming back.”

And that’s the paradox. However vicious, however vile, Coulter’s words fall under the protection of the First Amendment.

“There is no hate speech exception to the First Amendment,” says constitutional law scholar Erwin Chemerinsky. “The government cannot prohibit speech simply because it is offensive, hateful, or even deeply disturbing.”

Legal experts note that unless speech incites imminent violence or constitutes a true threat, it remains protected—even if morally indefensible. Courts have consistently ruled in favor of protecting unpopular or outrageous speech, citing the “marketplace of ideas” principle. As Justice Anthony Kennedy once wrote, “Inconvenience does not absolve the government of its obligation to tolerate speech.”

This principle isn’t abstract. It is central to American democracy. As author Christopher Hitchens put it, “The right of others to free expression is part of my own. If someone’s voice is silenced, then I am deprived of the right to hear.”

Coulter’s tweet is a test of that principle—a reminder that the First Amendment is designed not for comfort, but for confrontation. For the battle of ideas to remain legitimate, even the repulsive must be allowed to speak, so long as it doesn’t cross legal thresholds into incitement.

Still, that doesn’t mean such speech should go unanswered. Leaders from Indian Country and beyond have spoken loudly and clearly: Coulter’s remark is not acceptable.

“We are a people who have endured colonization, cultural genocide, and assimilation,” said Hoskin. “We are still here. And we will not be silent.”

But in the final calculus, Coulter’s words remain protected.

The First Amendment is not a tool for the righteous—it is a shield for the offensive. And however much it may sting to admit, scholars defending free speech argue even language that celebrates historical atrocity cannot, and must not, be outlawed simply for its indecency.

(James Giago Davies is an enrolled member of OST. Contact him at skindiesel@msn.com)

The post Hate speech first appeared on Native Sun News Today.

Tags: Top News