Lesson learned from the book ‘Sapiens’: Tribes fail because they cannot cooperate

RAPID CITY— A couple of years back a meeting was held at Rosebud Casino, chaired by Elgin Bad Wound with assistance from Leonard Little Finger, among others. Those in attendance were met, in earnest, to find a way to bring all the disparate and far flung divisions of the Oceti Sakowin together in common cause, from Fort Peck, to Pine Ridge, to Shakopee, to Spirit Lake, with one resolute purpose— the return of the Black Hills.

Wise words were spoken, sage counsel was given, but in the end nothing came of it, and dissension could not be held at bay even during the course of the meeting. Both Bad Wound and Little Finger have since journeyed to the spirit world, and the Oceti Sakowin are no closer to the purpose of that meeting than they were the day before it was held.

The question, then, and now, which every tribal member and tribal ally must ask, is why?

There is a pattern to the failure of Sioux people to unify and cooperate. This pattern escapes even the wisdom of our tribal councils and respected holy men. It hides in plain sight, and so it can never be confronted, and no plans have ever been crafted to defeat it. It would take a remarkable genius to even identify the problem. Tribes have been unable to work together long term, in any critical opposition to the European invasion of the New World. But why is that? Not only should we ask what stops tribes from working together, why does the European invader do a much better job of working against tribes?

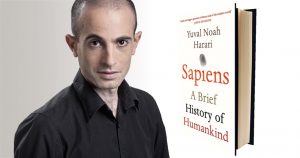

Enter the remarkable genius. In 2015 the Israeli historian, Yuval Noah Harari, wrote a ground breaking book, Sapiens, which analyzed the structure of human excellence. The book asked why can humans do the amazing things humans do, how did we build the Mayan temples, the Great Wall in China, split atoms, send men over 200,000 miles into the dark depths of outer space to walk on the Moon?

Although Harari acknowledged our superior intelligence, our opposable thumb, two things generally credited as the main factors for why we are superior to animals, he theorized a deeper, more comprehensively influential reason— humans are the only animals that can cooperate flexibly, and in large numbers.

This seems like a byproduct of the first two gifts mentioned, but those two gifts are really the tools used to establish the large scale, flexible cooperation. Social insects cooperate in large numbers. Social mammals cooperate flexibly. But only humans can combine the two. Harari said that, in the competition of life, one chimp might be superior to one man, but that a thousand men could easily defeat a thousand chimps. Humans routinely fill up stadiums with tens of thousands of people, and sophisticated networks of cooperation make this large scale reality possible. But a hundred thousand chimps in a sports stadium? “Complete madness,” Harari said.

Having established that humans are capable of large scale flexible cooperation where other species are not, Harari anticipated the next question we would ask, how do we do it?

This is where the theory gets controversial, where people become viscerally averse to the conclusion, and why the Europeans were able to seize the New World from aboriginal control. While Harari never addresses the New World conflict, profound conclusions can readily be inferred from what he does address.

Imagination, according to Harari, is the fuel that powers the engine of flexible, large scale human cooperation. Humans can create fictional realities on top of objective reality, and as long as a critical number of people believe the fictions, there can be cooperation, and the fictional reality is perceived as real. It is not just networks of physical cooperation, though, and it is not only adherence to the same rules and beliefs, Harari speaks of money, how this is a fiction we all believe. Money itself is just a piece of paper, it only has value because we all believe that it does. He uses Osama Bin Laden as an example: he hated America, our politics, our culture, but he had no problem with American dollars. “He was,” Harari said, “quite fond of them, actually.”

Once Europeans reached the New World, their fictional reality was primed and ready to plunge headlong into the vast, resource laden wilderness. In the recent past, competing fictional realities had altered the course of human history. The Crusaders had battled the Muslims for control of the Middle East. Both fictional realities were deep, rich and powerful, and took turns wresting the upper hand, and it required centuries before the European fictional reality won out. But once it did, a colonizer imperative drove the subsequent retooling of the fictional narrative, and the Europeans were set to exploit the far flung corners of the aboriginal controlled planet, ruthlessly dispensing with sentimentality.

Opposed to this exploitative, colonizer fictional reality, were the competing fictional realities of the aboriginal tribes of the New World. But from the day Columbus strode onto the white sand beaches of San Salvador, no tribe has been able to convince enough other tribes to craft a grand fictional reality, deep enough in scope, vision, and spiritual fervor, that it could do what the Muslims could not, defeat the Europeans. In this case, defeat the European plan to exploit the New World, from New York to California, from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego.

Throughout the history of the colonization of the New World, time and again we see tribes, and tribal alliances, abjectly failing at large scale, flexible cooperation…not in a sense relative to each other, but when compared to the depth of cooperation exhibited by the European invader.

After the French and their tribal allies defeated the British at the battle of Monongahela in 1755, they seized control of Ohio for three years. They could have pursued acting British commander Thomas Dumas into Pennsylvania, but this proved impossible because they could not keep large scale, flexible cooperation among their forces. The tribes had kept their word. They had fought and dispatched the British and killed commander Edward Braddock. The road was open for aggressive action into western Pennsylvania, which was in disarray.

But these tribes had their spoils, and they wanted to go home. What is generally misunderstood by Europeans is these warriors were not soldiers. Back in their villages they were heads of household. They were warriors where and when circumstances dictated, and for the duration of the circumstance. They did not have a capacity for long term war that would involve prolonged commitment beyond the original, limited-in-scope, promise given. This was perfectly honorable and reasonable behavior by the best standards of their life experience.

More than that, there is nothing savage or inferior about this behavior, in terms of being sensible and respectful of people and their individuality. European manifest destiny could teach any tribe far more about savagery than tribes could ever teach them.

In this modern world, traditional tribal concepts of fairness and justice and compassion might even be a more civilized way to conduct ourselves, but back in historical times, the conflict refined cooperation strategy of the European invader ran roughshod over all other strategies.

Throughout history, those peoples who best maintain flexible networks of sustained cooperation win wars. The rightness or wrongness of their actions does not factor into that outcome. Tribal peoples can only win battles, or at best, campaigns, like at Monongahela, or at Little Big Horn in 1876.

But their inability to cooperate is not restricted to history and conflict. It persists to this day on almost every reservation, at almost every level, in tribal IRA governments, in administering 638 contracts, in organizing agencies, programs, departments, policies, causes, activism. There is no aspect of any part of tribal life that is not compromised by the inability to create, apply and maintain cooperative, well organized networks that can compete with the cooperative reality the European invader has established and oppressively fine tuned.

The Oceti Sakowin can still organize a single body to consult with the federal government for the return of the Black Hills. For this effort to have any chance of success, the cooperation between all the tribes must be well organized, comprehensive, flexible and determined. Those four critical factors have proved an operational impossibility for about a century. Before the Oceti Sakowin can even begin the monumental task of establishing such a cooperative network, they first have to understand they don’t have one, why they don’t have one, and what it will take to start and maintain one.

(Contact James Giago Davies at skindiesel@msn.com)