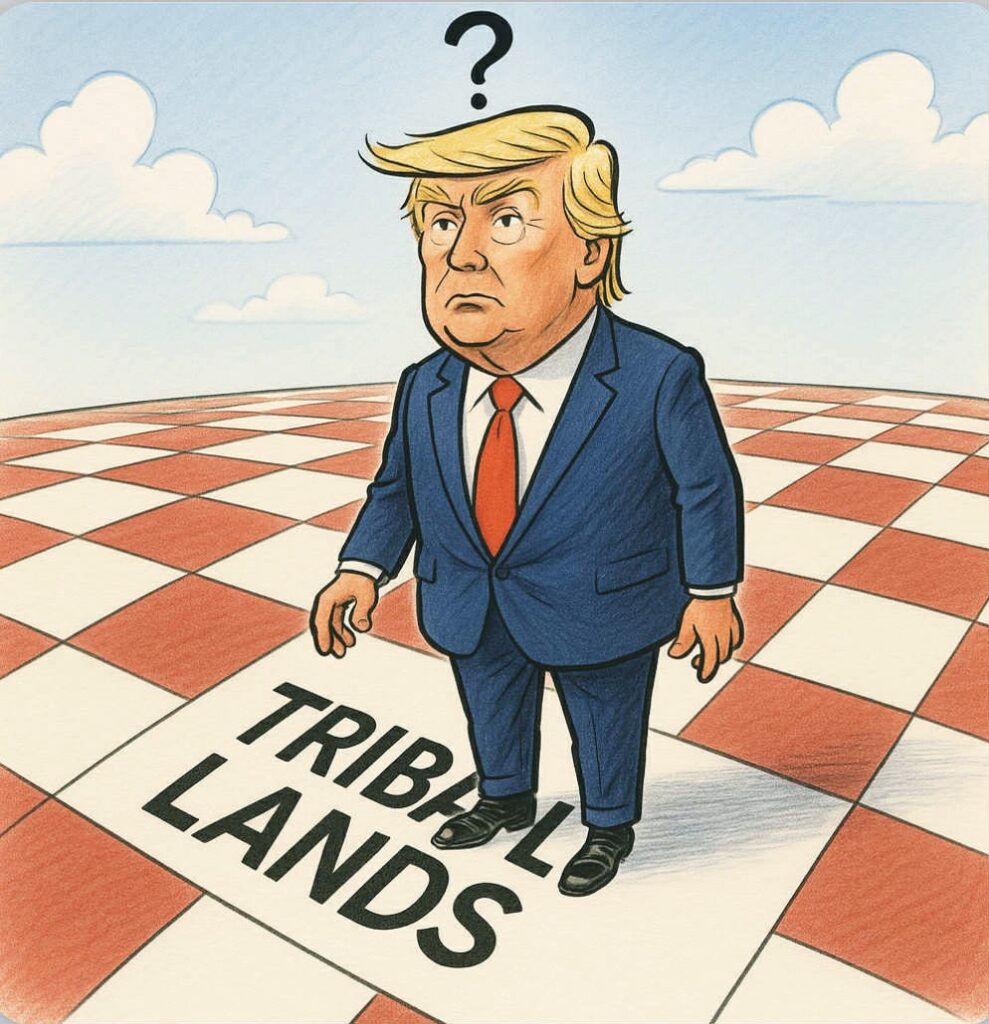

Trump’s checkered history with tribes

When Donald Trump took office in January 2017, he inherited a long and complicated history with Native American tribes — a record that, viewed in full, resists the caricatures that have defined much of the coverage over the past decade.

From high-profile casino disputes in the 1990s to a letter of support for the Cowlitz Indian Tribe in 2000, from the confrontation at Standing Rock to his nomination of a justice who became Indian Country’s most consistent ally, Trump’s dealings with tribes reveal a leader driven less by malice or affection than by calculation — one who could be unexpectedly generous to friends, yet dismissive when principled opposition exposed his flaws.

Trump’s first encounters with tribal governments came as a New York developer and casino owner in the 1990s. In 1993, he testified before Congress that “organized crime is rampant on Indian reservations,” a charge federal agencies found no evidence to support. Seven years later, he funded racially charged ads opposing a planned St. Regis Mohawk casino in upstate New York, leading to a $250,000 fine for failing to disclose his sponsorship.

But that same year, after the Cowlitz Tribe in Washington state gained federal recognition, Trump sent Chairman John Barnett a gold-monogrammed letter expressing support for “the sovereignty of Native Americans and their right to pursue all lawful opportunities.” He toured their proposed casino site and offered to develop it. The tribe declined, citing unfavorable terms, but Barnett kept the letter “just in case he becomes president someday.”

By far the most public tribal dispute of Trump’s presidency began before he took office, at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. In the national telling, the Dakota Access Pipeline was routed without proper consultation, and water protectors faced militarized police to defend sacred land and the Missouri River.

Court records tell a different story. U.S. District Judge James Boasberg later wrote that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had made “dozens” of attempts to consult with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe (SRST) between 2014 and 2016. The Corps documented meetings, letters, and site visits, many of which went unattended by SRST.

In August 2016, SRST sued to halt the project under the National Historic Preservation Act. On September 2, enrolled tribal member Tim Mentz, the leading expert on Oceti Sakowin sacred site preservation, filed a declaration identifying stone features and burials near Highway 1806. The next day, bulldozers cleared a two-mile stretch on private land in that area, sparking a physical confrontation between protesters and pipeline security — an incident that drew international attention.

Boasberg denied the injunction on September 9, saying the Corps had “likely complied” with consultation requirements. That same day, the Obama administration paused the Lake Oahe easement for further review. On December 4, 2016, the Army formally denied the easement and launched an environmental impact statement.

Trump reversed course within weeks of taking office. One of his first actions as president was to sign an executive order permitting work to resume on the Dakota Access Pipeline, a move that further exemplified his administration’s approach to Native issues.

On February 8, 2017, the Corps terminated the EIS process and granted the easement. To the administration, the issue was a procedural fix — not a sovereignty dispute. To critics, it was proof of hostility toward tribes.

The pattern at Standing Rock mirrored Trump’s broader approach: transactional, process-driven, and indifferent to symbolism. He reduced the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase–Escalante national monuments over tribal objections, arguing for greater local control. His Interior Department fought the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe’s land-into-trust status. Yet in 2017, the Justice Department declined to challenge the Cowlitz Tribe’s trust lands at the Supreme Court.

Tribal advocates saw a president who rarely took their side. Those who knew him personally described a man capable of warmth and loyalty to friends, but quick to turn on allies should their public comments conflict with his actions or policy.

Trump’s most consequential act for tribes may have been one of his earliest: nominating Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court in January 2017. Chosen for his constitutional originalism, Gorsuch had a record on the 10th Circuit of siding with tribes in cases involving sovereignty and treaty rights.

On the Court, Gorsuch became the decisive vote — and often the author — of landmark pro-tribe decisions. In McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020), he wrote the 5–4 opinion holding that Congress had never disestablished the Muscogee (Creek) reservation: “Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word.”

He joined the majority in Herrera v. Wyoming (2019), a case with direct Trump administration involvement. Clayvin Herrera, a Crow Tribe member, was convicted in Wyoming for killing an elk out of season in the Bighorn National Forest. He argued his 1868 treaty right to hunt on “unoccupied lands of the United States” still applied. The Wyoming courts disagreed.

The Justice Department under Trump opposed Herrera’s claim, arguing the treaty right had ended when Wyoming became a state and that the forest was not “unoccupied.” But in a 5–4 ruling, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote for the majority that the treaty right survived statehood and that the forest was unoccupied when created. Gorsuch sided with the tribe.

From Cougar Den (2019) on fuel taxes to Ysleta del Sur Pueblo v. Texas (2022) on gaming rights, to his dissents in Castro-Huerta (2022) and Arizona v. Navajo Nation (2023), Gorsuch has consistently read treaties as binding promises and defended tribal sovereignty.

Standing Rock also revealed how the national media’s treatment of tribal issues can lock into a simplified moral arc. In 2016 and 2017, news outlets amplified the imagery of water protectors clashing with security forces, but largely left unexamined the consultation record, the role of unqualified THPOs, and internal political rifts.

Once fixed, that frame was hard to dislodge. Monument reductions and pipeline approvals were interpreted as extensions of Standing Rock, while quieter episodes — like the Cowlitz trust land defense or Gorsuch’s rulings — received less sustained attention.

That loop has consequences. For many Americans, Trump’s image on tribal issues is frozen as the villain of Standing Rock. For those inside Indian Country who tracked the full record, the story is less about a single villain and more about a leader who neither struts nor frets over the fate of tribes, but acts according to his immediate goals.

In the end, Trump’s record with tribes is not a story of friendship betrayed nor enmity confirmed. It is a ledger of transactions, some cutting against tribal interests, others supporting them, and one Supreme Court appointment whose influence will likely outlast all of them.

(James Giago Davies is an enrolled member of OST. Contact him at skindiesel@msn.com)

The post Trump’s checkered history with tribes first appeared on Native Sun News Today.

Tags: Top News