When Candy met the Mad Lads

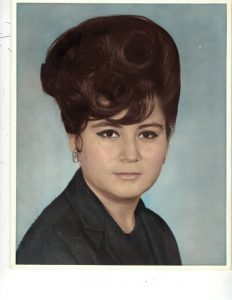

RAPID CITY— Think back to when you were fourteen years old. We all have common experiences. Like being asked up on stage to replace the singer who has a sore throat, and singing a couple of Beatles songs so well the band asks you to join the band. Okay, so that is not a common experience, but that is what happened to Olivia Gonzalez.

RAPID CITY— Think back to when you were fourteen years old. We all have common experiences. Like being asked up on stage to replace the singer who has a sore throat, and singing a couple of Beatles songs so well the band asks you to join the band. Okay, so that is not a common experience, but that is what happened to Olivia Gonzalez.

Before that happened, Olivia had spent her formative years, living in little towns all across the state of South Dakota.

“I was born on July 5, 1950, at Lake Andes,” Olivia said. “My dad was there working on the dam at the time. I grew up, in my earlier years, at Kadoka. I think they moved there like when I was two years old and we lived there until I was 12. Went to school in Kadoka…we lived on a street that was pretty much known as Indian Town to the rest of the town, because it was us and all our relatives on one street.”

In those days, Kadoka was a much larger town, and for whatever reason, a favorite stop over for tourists. Being the daughter of a Lakota mother and a Hispanic father gave Olivia an identity so distinct it isolated her not only from the community around her, but from the world at large. Only in Indian Town could her family be themselves.

“My dad was a construction worker,” Olivia said, “and so he worked on making bridges all across I-90 and I-29, and we moved across the state every time his job moved. Because the last couple of bridges were closer to Box Elder, we started going to school at (Ellsworth) Air Force Base, which was a life changing event in and of itself. All of a sudden there were kids from all over the country and the world, it was just an enlightening experience. Prior to that time, I had really bad introverted qualities. I was afraid to even get up and give a speech at school when we first started. I broke down and cried, said I couldn’t do it. I was thirteen then.”

Douglas High School had opened only a few years before. At no other place could Olivia have met the diverse kind of people that would so quickly recognize her talent or give her an opportunity to express it.

“That following summer,” Olivia said. “My mom heard there was a band playing down at the corner from where we lived out in Box Elder. The lead singer was singing J. Frank Wilson’s ‘Last Kiss,’ and everybody was saying they were really good, and the guy that was singing at the time, made a comment that he was having a hard time, he had a sore throat, so if anybody out there would like to sing for me, come on up. and my mom nudged me, and I said, I can’t do it. She nudged me several more times and she said if you don’t get up there and sing I am not going to take you out to listen to any more bands.”

Given she had already broken down and cried the previous school year, when forced to stand up and perform in front of others, Olivia had come to a crossroads in her life; remain sitting and let the moment pass, or get up there, face her fear, and sing like she knew she could sing.

“(Mom) was a music lover,” Olivia said. “And she passed it on to us. If my mom said something like that, I knew she meant what she said, so I made myself get up there. He asked me if I knew any Beatles songs and I said, yeah. I sang ‘Hard Days Night,’ and then he said, how about another one, and the second one was ‘I Shoulda Known Better.’ My knees were shaking; I was really overwhelmed. I got off the stage, everybody was clapping and the band took a break. They came back about 15 minutes later and they said how would you like a job?”

This was how a band started that was good enough to be remembered half a century later, and be considered for the South Dakota Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame.

“They were known as the Mad Lads, and I was introduced to the group by a neighbor who couldn’t remember how to say Olivia. She said I can’t remember your name, I am just gonna call you Candy, so when she introduced us she said this is Candy, and when they hired me they changed the name to Candy and the Mad Lads.”

Candy and the Mad Lads became a regular fixture around the Black Hills Area in the mid-Sixties. That was a different time. The only way people could hear music was on the radio, usually mono, and only the music the station bothered to play, and you had to sift through commercials and DJ banter just to maybe hear your favorite song sometime during any given day. Also, there was no karaoke. As a result, bands were everywhere, as were venues where they could play, because live music mattered to people who wanted to have a good time and dance.

“I worked with Candy and the Mad Lads until my brother-in-law got sent to Guam,” Olivia said. “The other three guys in the band decided they didn’t want to have that many people in the band anymore, so they let me go. My Dad took me to Philip, and there was another band that was playing in the area that hired me that same night, so I worked with them. Their name was Denny and the Darnells.”

That was when fate came calling for Olivia Gonzalez. But she could not know at the time, how fleeting and unforgiving that call would be.

“Some gentlemen came in from Sioux Falls and listened to me sing,” Olivia said. “They had heard that I sounded like Brenda Lee. So they hired me to sing at a nightclub in Sioux Falls. My dad took me over there and they paid for our hotel room and everything and I had a nightly showing that nightclub. I was fifteen years old. We stayed there for that summer and they had some connections up in Minneapolis, and were prepared to offer me a recording contract. They wanted to take me up to Minneapolis and cut some demo records, and they started talking about getting me a contract and buying me a wardrobe and all, and then one of them made a comment that my Dad didn’t like. He said, we are going to invest a lot of money in you, so you can’t turn around and go do something stupid like get pregnant.”

The gate of fate swings both ways. Maybe those guys lost out on the same opportunity that Olivia did by forgetting to be respectful to a fifteen-year-old girl in front of her dad. Whatever the case, this was the only opportunity Olivia would ever receive of that nature.

By 1982, at the age of 32, she came to the second crossroads in her life, a divorce, and after the divorce, she needed a fundamentally fresh direction in her life, considering her band had broken up, and she had been laid off from her job.

“I actually went with two of my sisters who were gonna enlist,” Olivia said. “Turned out I was the only one with a high school diploma, so they couldn’t go, but I did. I went to Fort Leavenworth and while I was there I organized a group with some of the guys I worked with and we had a band called Axis and we performed at company picnics and military things on base.”

Olivia’s life had become a strange dichotomy of unusually timed situations. In the first, she was only fourteen and singing in nightclubs. In the second, she was past thirty and joining the Army.

“Since 1985, I’ve not really performed regularly with any bands,” Olivia said. “I’ve made guest appearances with Family Affair, Dustin Rocks and Crash Wagon, they play sometimes over here at Elk Creek, or they play at Robbinsdale. My singing since 1990 has largely been karaoke. I couldn’t find any band members to work with when I got out of the Army so my daughter helped me buy the equipment and I just started playing karaoke in some of the bars here in town and out in Box Elder.”

Even now, at the age of 69, sitting in a lawn chair, Olivia can sing, and unlike us, she hits every note, and she puts her signature stamp on them, so they resonate far beyond what most of us could accomplish with a karaoke mic in hand.

(James Giago Davies is an enrolled member of the Oglala Lakota tribe. He can be reached at skindiesel@msn.com)