Bruce Bad Moccasin: Pulling up the bootstraps

RAPID CITY—Bootstraps are what the white folks around Chamberlain expected folks to pull themselves up by. However humble a person’s beginnings, if he yanked on those bootstraps hard enough, he could make himself a big success in life. It is hard to say how Haapikceka Sica, Bad Moccasin, got his name, translation being a tricky thing. But he was one of thousands of Mdewakaton Dakota forcibly relocated from their ancestral home of Central Minnesota to the present-day Crow Creek Indian Reservation in 1862. Over 1300 Mdewakaton would die of starvation, but Bad Moccasin would survive, and 87 years later his descendant, Donald Bruce Bad Moccasin would be born at Chamberlain, where bootstraps for small, skinny Indian boys, to this day, are in desperately short supply. But throughout his life, no travail ever lessened the grip Donald Bruce Bad Moccasin had on his bootstraps.

Most folks called Donald Bruce Bad Moccasin, “Bruce,” and Bruce was born with two gifts, one which would soon become obvious. The other gift would take long years to reveal, but in the end, would prove the greater gift.

“When I was about two years old, my parents moved to Pierre,” Bruce said, after settling comfortably into his easy chair. A 2005 stroke has forced Bruce to choose his words with care. “My parents had five kids; I was the youngest. My dad wanted a job there. There was no housing…well, they had some, but not for Indians. Most of the Indians that went to Pierre, they lived in tents. Our family had two tents. We stayed there for about a year, and, of course, the winter in a tent, was cold.”

Eventually the family moved to a house, a downtown rental Bruce’s dad secured from his employer. Bruce described it as a big house set up for Indians. It was not long before basketball started to make its mark on the Bad Moccasin family.

“My oldest brother, Dick, he was a basketball player for Pierre, 1957-58,” Bruce said. “He was a starter, a guard, with the Governors. After graduation he left and went to the Army. All my brothers and sisters they went to Stefan boarding school (on Crow Creek) but I stayed in Pierre, I stayed with my parents, because I had to help them, gather wood, fuel.”

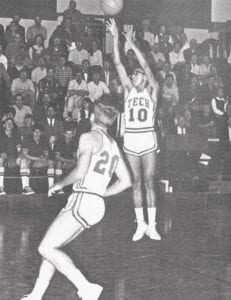

It was not readily apparent that Bruce would be a basketball success. He was small and skinny but whatever sneakers he put on had gigantic bootstraps that made him the most gifted player on the floor. His feet, his hands, were exceptionally quick and clever, and once those hands grew big enough to properly grip the basketball, he proved a deadly shooter.

“We lived close to the Boys Club,” Bruce said. “Every day I would go over there, play mostly basketball. I was the youngest guy. I had two brothers and they said you can play with us, but you can’t shoot, you’re too small. What you do, you pass to me. That became my deal, passing the ball. I did that for a while, until I got bigger, and then I could shoot. The Boys Club had a team, and the coach said, do you want to play for our team, you’re here every day. You can start at guard. You can dribble, you can pass, everything. I played on the team for a couple of years. The school had a team. So, I played for the junior high school teams. I started on all of them.”

Finally, Bruce wound up at Pierre High School: “I started with the B team. You couldn’t be varsity, you had to play on the (sophomore team). My coach in high school, Roger Pries, he was from Watertown. He was a big man, and he was a quiet guy. He told me you’re quick. He had plays for me, and people would say we couldn’t hardly get him because he had so many screens all over. Games were tough, like against Rapid City Central. They were just one high school then, and we had a friend Marty Waukazoo (who played for Rapid City). Marty, like all of us, we were skinny people, young people. He had long arms, long legs. One game in Pierre, Rapid City’s Coach Dave Strain, he talked to me a lot. He liked to talk to Indian people. Anyway, Coach Strain put Marty against me, and of course Marty is tall, but Marty was too slow for me, so they took him off me after a while. Rapid City had people like Jim Lintz, they were tall people, football players, and they were tough. We beat Rapid City, but most of the time they beat us.”

In the semi-finals of the state tournament in 1967, Pierre lost to Rapid City, but Bruce was named First Team All-State. Limited opportunities awaited most Indian athletes after high school, but Bruce would prove to be the exception.

“I liked all sports,” Bruce said, although he adds he was too small for football. “Mostly running. My parents had no car, so you had to walk or run, so wherever I went, I ran, and in town people called me the Indian Runner because that’s all I did. Whether it was basketball, or church, or downtown, or whatever, I’d run.”

Like a lot of Indian athletes Bruce had a unique mixture of fast and slow twitch muscle fiber. This allowed him to be the quickest player on the basketball court, and still have the stamina to excel at cross country. When his all-around athletic excellence was combined with his academic excellence, every local college wanted Bruce at their school. He went to South Dakota State and toured their campus, but he said, “They were just too big.” Rapid City’s School of Mines and Technology struck him as a perfect fit. But courses are tough at Tech. To be a Hardrocker means limiting the time you have for academics at a school with a high drop out and transfer rate even for students not splitting their time with athletics.

The academic counselor at Pierre had told Bruce that he would make a good teacher, but Bruce said, “I don’t want to be a teacher. I want to be an engineer. Because my dad worked outside. Hard work outside, I worked for him sometimes, and I told him I want to be an engineer, not a laborer, where I go in an office somewhere. Draft, survey, that’s what I wanted to do.”

“They had a new coach at the School of Mines, Jim Kampen,” Bruce said. “He’s from a little town east of Aberdeen. He was a young man. He was a runner, cross country, basketball, and track. He called me one day in Pierre and he said you ever think about the School of Mines? He said, you show up you can play basketball, run track, whatever. I said, well, yeah, but I wanna be an engineer, that’s my job. I did one year of cross country. I liked it, but it took a lot of time from my studies. One week after cross country was done, then you start basketball, no time off.”

Come the spring, Bruce ran the quarter and half mile in track. It was a heavy load for an eighteen-year-old kid.

“My grades were going down, “Bruce said. “I met with my counselor and he said one of those sports is gonna have to go. You need a tutor to (catch up) with your courses. So, I said no more cross country. I decided to keep basketball and track. The coach said if you make the first two years at Mines, you’re okay. You look around, he said, and in two years two of the people next to you are going to be gone. I looked around and I said, one of us is gonna be gone, maybe me!”

Bruce made the cut after two years. His grades picked up as he got into the meat-and-potato courses of the third and fourth years, because he was finally focusing on the skills he needed to become the engineer he had dreamed of becoming.

One thing every young man had to face in the late Sixties was the military draft. Being in college protected you from being drafted, but not completely, so if he had to serve, Bruce figured it would be as an officer, so he signed up for the Army, committing himself to two years of service after he was graduated from Mines.

After graduation Bruce was commissioned as a second lieutenant. By 1973, Vietnam was winding down, so he attended three months of Officer Training School in Washington D.C. and then he went into the reserves, where he served for seven years.

His first job was with the BIA, building roads on South Dakota reservations. Bruce: “I did survey, draft, everything. I stayed with the BIA as an engineer for about five years.”

“I decided I was gonna go to the Indian Health Service (IHS),” Bruce said. “They had what is called a commissioned corps, which is in the public health service.”

Engineers were needed to work on water and sewer systems, on landfills, to maintain a safe health standard, so Bruce was sent to Oklahoma City where he became a design engineer. In 1981 Bruce went back to the School of Mines and got a master’s in civil engineering.

As his career progressed, he eventually became the IHS Regional Director. His broad knowledge of all aspects of IHS served him well in that position.

Eventually, Bruce and his wife Rita moved back to Pierre, and one night after taking in a movie, Bruce started to feel strange. “I didn’t know what was happening to me,” Bruce said, “but I was having a stroke.”

“It took his speech,” Rita said. “He had to learn to read again. I went to him with him to every therapy. What he did in therapy during the day, I would do at night with him. I always asked his therapist to give me homework to do with him, and she said, you know, in all the years I been doing this, you’re my first patient’s wife that stays during the whole time.”

Working together, Rita and Bruce got Bruce back to where he regained full mobility, and although he sometimes confuses dates and names and terms, his mind is still lucid, but more importantly, he retains that other gift, greater than his athletic gifts. Throughout his life, against great odds, and from a beginning of poverty and marginalization, Bruce Bad Moccasin never ceased to be kind, gracious, resourceful, and determined. At the Boys Club, everybody liked Bruce. At Pierre High School everybody liked Bruce. At the School of Mines, everybody liked Bruce. In Oklahoma City, working for tribes who wondered who he was, where he was from, and just assumed that because he was an Indian he could not be an engineer, everybody grew to like Bruce. People liked Bruce because however much he aged and changed, internally he never stopped running, or dribbling, or shooting, or studying, or soldiering, or engineering, or being a leader, or just being a nice guy. Even a stroke could not take all those qualities and accomplishments away from him.

“Nobody remembers who I am anymore,” Bruce said, referring to a basketball career that ended long decades ago. Bruce is also not listed as one of the prominent members of his tribe on the Crow Creek Wikipedia page. But he should be, not just for sports excellence, but because of the ikce wicasa example he set for all Oceti Sakowin, long after he dribbled his last basketball.

(Contact James Giago Davies at skindiesel@msn.com)

The post Bruce Bad Moccasin: Pulling up the bootstraps first appeared on Native Sun News Today.