Analysis:

By Andrew Malo

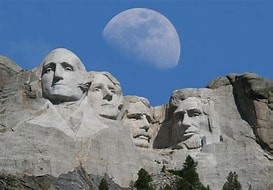

Should Mount Rushmore be destroyed? We look at America’s past in the Black Hills, the meaning of the Black hills to the Lakota, and the faces that are carved into Mount Rushmore to find out.

Though I have visited—and thoroughly enjoyed—the Black Hills many times in the past, I have never seen Mount Rushmore, also known as “The Shrine of Democracy.” In fact, I actively oppose going near it.

It rubs me the wrong way. Even before I knew anything about it and why it was there, it felt off. Admittedly, most of my aversion was an aesthetic one. I think it’s a strange desire to want to use dynamite and chisels to carve into mountains and put faces on it. Learning more about the monument strengthened my resolve.

According to the document “The Meaning of Mount Rushmore” in Mt Rushmore’s Hall of Records:

“The four American Presidents carved into the granite of Mount Rushmore were chosen by sculptor Gutzon Borglum to commemorate the founding, growth, preservation, development of the United States.”

Though these presidents do represent those qualities to many Americans—and let it be known that I am a proud American—in the spirit of one of our greatest writers, James Baldwin (“I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually”), I object to these faces being seen in the Black Hills of South Dakota and, therefore, am of the opinion that it should be destroyed.

My opinion comes from:

1. America’s troubled past in the Black Hills

2. The Black Hills are sacred

3. The faces that are carved into the granite bluff on Lakota land.

Before we get into that, though, let’s take a quick look at the history of Mount Rushmore.

History of Mount Rushmore

Mount Rushmore was the brainchild of Doane Robinson, a lawyer and historian in South Dakota. He originally conceived Rushmore as a tourist attraction along Needles Highway, with heroes of the old West, such as Lewis and Clark, Sacagawea, Red Cloud, etc. carved in. His first choice for carving, Lorado Taft, was too ill to do the project, so he reached out to Gutzon Borglum, who was busy working on a carving of Robert E. Lee at Stone Mountain in Georgia. It should be noted that Borglum was a known white supremacist and had affiliations with the Ku Klux Klan.

Borglum agreed to the project and came to visit to find the spot. Borglum thought Needles was too delicate for carving, but found a spot that he thought would be perfect – a granite bluff called “Six Grandfathers” by the Lakota. Borglum convinced Robinson that the faces should be that of the presidents and not western heroes, as it was too regional. Robinson agreed and work began in 1927 and finished in 1941. Nearly 3 million people every year visit the National Monument.

America and the Black Hills There are many ways to tell the story of America’s relationship with the Black Hills, but they all come down to the US stealing from the Lakota. Not only in the sense of “settlers” coming to squat on Indigenous land to claim it and hoping the US government would protect them, but by US standards of law, also.

After General William Tecumseh Sherman slaughtered nearly all the buffalo in an attempt to exterminate the tribes of the west by cutting their food source (a scorched-earth tactic he used in the Civil War against the South), Sherman sat at the table with Red Cloud in 1868—who just got done whipping the US forces all over Wyoming and Montana—and they signed the Fort Laramie Treaty, which promised the Sioux Nation the Black Hills (and all of western South Dakota) for perpetuity.

Forever never lasted long when it came to treaties with the Native tribes (every single treaty the USA has made with Indigenous people have been broken) and, almost as quickly as the ink was dry, little General Custer wanted more glory in his bucket so he set out on an expedition into Sioux land—at the behest of the US Government—to search for a location for a fort, as well as natural resources in 1874. They found gold.

Custer sent word to the East, which the press broadcasted loud and clear for miners. Thousands of miners trespassed onto Lakota land and started camps like Lead and Deadwood. Within a year, after trying and failing to persuade the Lakota to accept compensation for the Black Hills ($25k) and move to Oklahoma, the US simply took the land illegally, started the Great Sioux War, and that was that. Even considering the widely-held ideals of American exceptionalism and manifest destiny at the time, it was low move.

One hundred years later, the Sioux were awarded $106 million over the illegally seized land, which they refused and continue to refuse until this day. The land is sacred.

2. The Spirit of the Hills

The Black Hills are sacred to the Lakota. As Leonard Little Finger, a Lakota elder and founder of Sacred Hoop School, writes:

“The Black Hills were recognized as the Black Hills because of the darkness from the distance. The term also referred to a container of meat; in those days people used a box made out of dried buffalo hide to carry spiritual tools, like the sacred pipe, or the various things that were used in prayers or to carry food. That’s the term that was used for the Black Hills: they were a container for our spiritual need as well as our needs of food and water, whatever it is that allows survival.”

That the sacred land was blatantly stolen, then desecrated with the Founding Fathers of the Nation who stole it, on the granite bluff named by the Lakota as “Six Grandfathers Mountain,” is insult to injury. In fact, it’s repulsive.

3. And Speaking of Those Founding Fathers…

Mohawk Military Leader Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant) once said of Washington: “General Washington is very cunning, he will try to fool us if he can. He speaks very smooth, will tell you fair stories, and at the same time want to ruin us.” (Img: public domain)

We reached out to the Tim Giago, an Oglala Lakota, founder of the Native American Journalists Association, and editor of Native Sun News Today for some guidance on the article, after reading his thoughtful and inspiring article on Rushmore. He graciously offered us some little known quotes from the Presidents who are carved on the rocks, which we will quote here in full for you. As you will see, the four faces that are carved into the Lakota’s hills had very clear feelings on Native Americans.

“Indians and wolves are both beasts of prey, tho’ they differ in shape.”

– George Washington

“If ever we are constrained to lift the hatchet against any tribe, we will never lay it down till that tribe is exterminated, or driven beyond the Mississippi… in war, they will kill some of us; we shall destroy them all.”

-Thomas Jefferson

“Ordered that of the Indians and Half-breeds sentenced to be hanged by the military commission, composed of Colonel Crooks, Lt. Colonel Marshall, Captain Grant, Captain Bailey, and Lieutenant Olin, and lately sitting in Minnesota, you cause to be executed on Friday the nineteenth day of December, instant, the following names, to wit…” –Text from President Lincoln to General Sibley ordering the execution of American Indians in Minnesota that initiated the largest mass hanging in American history. 38 men were hanged.

– Abraham Lincoln

“I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.”

– Theodore Roosevelt

Perhaps this is a rhetorical question (though maybe not – read an article written by the great-granddaughter of Gutzon Borglum), but I feel it is a necessary one. From research, I’ve noticed Indigenous people who write of Mount Rushmore often refer to it as “The Shrine of Hypocrisy.”

On the National Park Service website it says, “Over the decades, Mount Rushmore has grown in fame as a symbol of America-a symbol of freedom and hope for people from all cultures and backgrounds.”

Clearly, the NPS is stating a false statement. Or, more accurately, a hypocritical statement. To an objective observer (as well as, perhaps, a person actually concerned with freedom and hope for all people), destroying a monument to individuals who enacted policy to take away freedom (i.e. land, culture, religion) and hope from Native Americans on land that was, by both Native AND American accounts, illegally stolen, seems to be the most logical and appropriate response. It certainly would be satisfying.

However, there is another question to consider. And that is what America is? Sometimes it’s easy to think it is a land of evil and cruelty. But I try to be hopeful. And in the most hopeful light, I think America is a land of contradiction – a place where we are constantly battling between our heavens and hells. And where, occasionally, the goods and evils are not what they seem or perhaps the evil is used for good or vice versa.

So having a ridiculously offensive monument on blatantly stolen land run by a government branch (National Park Service) that generally tries to be fair-minded might amount to something useful for humanity. To remind us of that hypocrisy. To show that this land is not ours, but stolen, from those who acted as caretakers of the earth instead of our idea of the land as being something to take from.

Because as we Americans further our scorched–earth standard of living—given to us by those men like General Sherman so long ago—by raping the land of its resources and bulldozing cultures that are connected to it, we might just learn that it is simply not sustainable and, more importantly… change.

(Compliments to Know the Place Magazine)

The post Analysis: first appeared on Native Sun News Today.